On February 11, 1829, a tragedy occurred in the capital of Persia that still causes controversy among historians.

An angry crowd stormed the Russian embassy. As a result, almost all of its employees died, including the head of the mission, Alexander Griboyedov, the author of the immortal “Woe from Wit”.

The last hours of the embassy

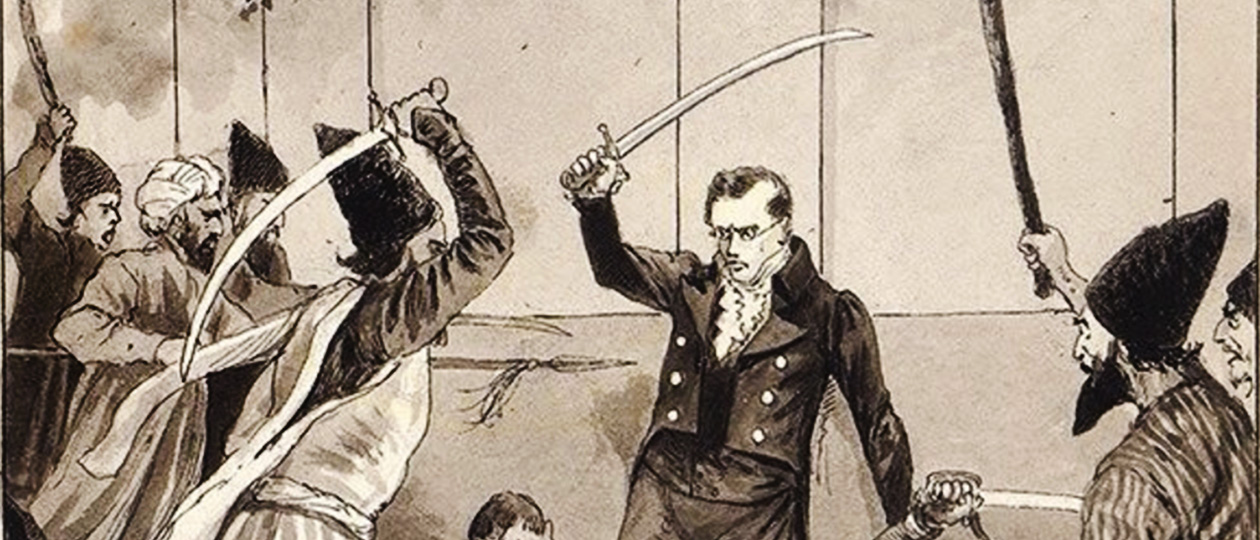

“They killed Alexander!” – these were the last words that Griboyedov uttered when the attackers broke through the roof of the embassy and killed his servant with the first shots.

The ambassador’s head was already covered in blood from the blow from the stone. Together with the remaining staff and the Cossack guards – 17 people in all – they retreated to the back room of the building.

The smell of smoke began to rise from the roof. There was no longer any hope that the Shah would send soldiers to disperse the maddened crowd.

The besieged were prepared to sell their lives dearly. Griboyedov managed to shoot several of the attackers before the tall Persian plunged his sabre into his chest.

The bodies of the dead were dragged out onto the street and dragged around the city on ropes for a long time with mocking cries of: “Make way for the Russian envoy!”

Three versions of the tragedy…

Version one: “It’s his own fault”

The official version, accepted by both sides, was that Griboyedov had shown excessive zeal and carelessness, thereby provoking the wrath of the local population.

Allegedly, he had behaved provocatively towards the Shah, and his men had harassed the locals and forcibly taken concubines from the harems.

However, this version does not stand up to criticism. Griboyedov knew Eastern customs and languages very well. Even his ill-wishers acknowledged the diplomat’s exceptional competence. “He replaced a twenty-thousand-strong army there with his own single face,” said military commander Nikolai Muravyov-Karsky.

Version two: “The British connection”

Many historians point to the possible involvement of British intelligence. England was playing the “Great Game” with Russia for influence in the region and was afraid of the strengthening of Russian positions in Persia.

It also looked suspicious that on the day of Griboyedov’s murder there was not a single Englishman in Tehran – “although at other times they followed the Russians step by step.”

However, no direct evidence of a British connection was ever found. Moreover, at that time London was interested in the stability of Persia and the preservation of a loyal dynasty in power.

Version three: Dangerous witness

The most convincing version is that the tragedy was caused by one person – Mirza-Yakub (Yakub Markaryan), a former eunuch of the Shah’s harem.

This Armenian, who worked for many years as a treasurer and keeper of harem secrets, decided to exercise his right under the Treaty of Turkmanchay and asked Griboyedov for help in returning to his homeland.

For the Shah’s court, Mirza Yakub was more dangerous than a modern Edward Snowden – he knew not only all the secrets of the harem, but also the financial secrets of the court.

In conditions when the prestige of the dynasty was shaken after the defeat in the war, and the people grumbled about the levies to pay the contribution to Russia, such a person represented a mortal threat.

The Perfect Crime

When the attempt to arrest Mirza Yakub on charges of embezzlement failed, a tried-and-true weapon was used: religious fanaticism. Rumors began to spread throughout the city that the defector was insulting Islam.

The supreme mullah called for the blasphemer to be punished and the mission that had sheltered him to be punished.

It is significant that the Persian guards of the embassy turned out to be unarmed – their guns “accidentally” were stored in the attic, from where they were taken by the attackers.

When the crowd went to storm, the governor of Tehran – the son of the Shah himself – locked himself in the palace instead of restoring order.

As a result, the Shah’s court got rid of both a dangerous witness and an overly principled ambassador who was seeking payment of the contribution.

Moreover, after the tragedy, Nicholas I forgave Persia part of the debt and postponed the remaining payments. And the people’s anger was directed not at the government, but at foreigners.

Epilogue

In the St. George Hall of the Winter Palace, the Emperor received the grandson of the Persian Shah, Khosrow Mirza, who had come to ask forgiveness for the “regrettable incident.”

A sabre hung around the prince’s neck, and boots with earth were thrown over his shoulders – an ancient symbol of repentance. Nicholas I uttered the historic phrase: “I consign the unfortunate Tehran incident to eternal oblivion.”

Griboyedov’s body was buried in Tiflis, at the Church of St. David on Mount Mtatsminda. His young widow Nina Chavchavadze remained faithful to her dead husband until the end of her life.

And another tragic and mysterious page entered Russian history – the story of how a talented poet and brilliant diplomat became a victim of a big political game in the East.