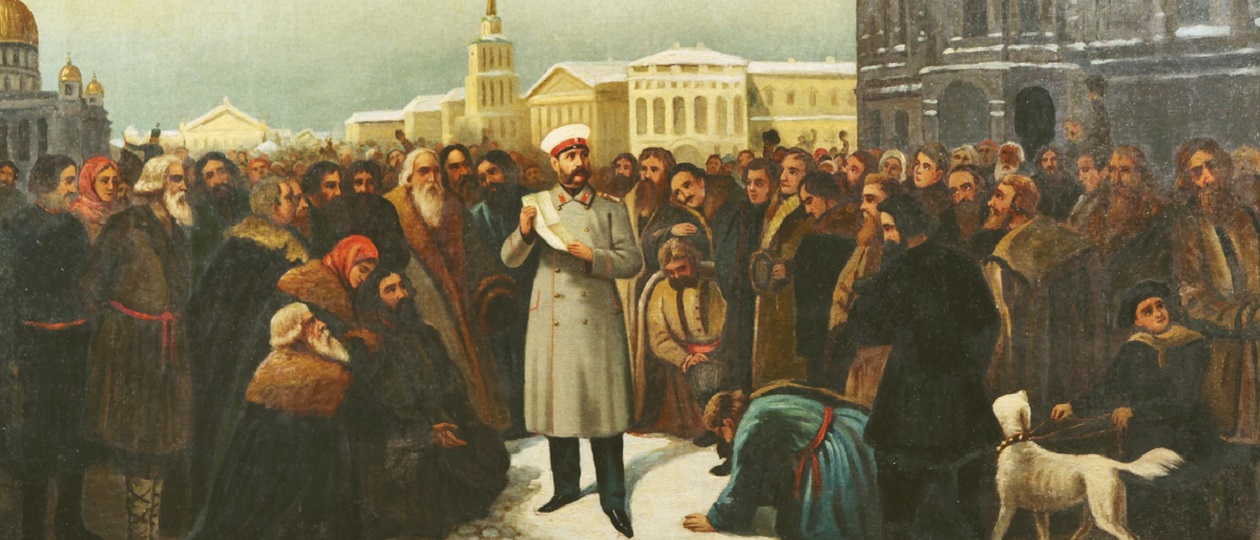

Historians generally agree that the People’s Will [Народная Воля] suffered a major defeat because it did not overthrow the government after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II on March 1, 1881.

At best, the assassination was a Pyrrhic victory because the successful assassination was accomplished at too great a cost for the People’s Will. The autocracy stayed in place for many more years until the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II in the February Revolution of 1917.

However, if we examine the activity of the People’s Will in the context of the history of terrorism in the Russian Empire, Europe, and the world, we will find that the People’s Will scored many significant victories. One can suggest that the organization experienced many more victories than defeats.

I do not engage in idealization or demonization of the narodovol’tsy [members of the People’s Will]. There have been too many elements of historical mythmaking in the history of this organization over the past 140 years. By stripping away the elements of mythmaking, we can come to a more objective understanding of the history of the People’s Will and determine just what made it unique in the history of terrorism.

The Choice of Terrorism

The People’s Will did not engage in indiscriminate terrorism as the terrorists of the early 20th century. Instead, they focused on delivering a <<blow to the center>> as Executive Committee member Aleksander D. Mikhailov put it. Assassination of the tsar —regicide — was their main form of terrorism. The People’s Will’s emphasis upon regicide was the logical result of the organization’s understanding of the nature of the Russian state. The narodovol’tsy believed that the Russian state was the main exploiter and oppressor of the people. This state was incapable of reforming itself and the narodovol’tsy saw the overthrow of the autocracy and the establishment of a representative form of government as making a socialist revolution possible. Alternatives for accomplishing the goal of turning Russia into a socialist society included: the combination of a political and social revolution; seizure of power with the help of the military but without the participation of the people and carrying out a socialist revolution from above; forcing the government to grant concessions such as a constitution and parliament which would then create possibilities for carrying a socialist revolution.

The People’s Will understanding of the nature of the Russian state determined its choice of regicide. Narodovol’tsy saw the main difference between Russia and Europe in the roles of the state and society. In European countries, society created the state, but in Russia, the state created society. The bureaucracy, army, church, nobility, and bourgeoisie were created by the autocracy and received their privileges from it. Russian social institutions simply could not act independently from the state and could not show any resistance to it. In European countries, these social institutions could freely compete with monarchies for the division of power. The Narodovol’tsy were convinced that the concentration of power in the hands of the tsar was the Achilles heel [weak spot] of the Russian state. Assassination of the tsar would lead to the quick collapse of the state and society.

As French historian and publicist Anatole Leroy-Beaulieu told his European readers <<One can say that, in many respects, the throne is the cornerstone of the entire social order. This is why the revolutionaries direct all their blows against the throne…Everything would fall apart with the throne because everything in Russia depends upon the throne.>>

The People’s Will correctly understood the nature of state and society in the Russian Empire. However, in hindsight, they simply chose the wrong method of getting rid of the autocracy. The abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in the February Revolution, and not an assassination, led to the speedy collapse of the Russian state and society in the eight months leading up to the October Revolution.

Successful and Unsuccessful Goals

The People’s Will formulated the major goals for terrorism and these goals remained in place in the early 20th century. Some goals represented victories, but other goals represented defeats. Openly stated goals included:

- Defending the revolutionary movement against spies, traitors, and cruel officials. This goal failed massively because of the joint work of police Colonel G. P. Sudeikin and Executive Committee member S. P. Degaev—who turned traitor—in crushing the Executive Committee and its satellite members in 1882-1883.

- Disorganizing the government through systematic assassinations and lowering its prestige before society and the people. The People’s Will hunt for the tsar certainly threw the government into panic and made it lurch back and forth between escalating repressions and considering concessions to society.

- Appealing to the people to carry out revolution because the government would be unable to defend itself. This goal was a failure because the peasants did not rebel against the government. The history of the People’s Will is the story of single combat between the government and revolutionary intelligentsia.

- Forcing the government to grant concessions in the form of political freedom, a constitution, and parliament. The narodovol’tsy believed that this would guarantee the support of liberals. However, the People’s Will saw political freedom only as an opportunity to conduct socialist propaganda freely and then carry out a socialist revolution. This, in their opinion, would guarantee the support of socialists who had opposed terrorism. This goal was partly successful because by early 1881, the government was considering a major reform to bring representatives of society into participating in the drafting of legislation.

The People’s Will had two major hidden goals and these goals resulted in major successes.

Using terrorism to provoke the government into taking a more severe repressive policy in the hopes that this would ignite a people’s revolution or create conditions for a seizure of power. This was a deliberate application of the Russian proverb <<The worse it is the better>>. This tactic inevitably played into the hands of government supporters of repressive policies. The major immediate result of the assassination of Tsar Alexander II was the proclamation by the government on August 14, 1881, of the Statute of measures for protection of the state order and civic peace. This statute remained in place until the February Revolution. In the long run, this repressive law antagonized many people and diminished the government’s base of support.

Using terrorism deliberately as a preemptive strike against the possibility of Russia being transformed into a European liberal state. Although the People’s Will said that it was fighting for political freedom, this does not mean that they wanted to see a parliamentary democracy established in Russia. Like all Russian socialists, the narodovol’tsy wanted to make a leap directly from feudalism to socialism and bypass the capitalist and liberal stage of development. Political freedom could create favorable conditions for conducting socialist propaganda and then carrying out a socialist revolution. Political freedom was never an end in itself for Russian socialists. According to the People’s Will, a long-term parliamentary democracy would only establish the power of the bourgeoisie and continue the exploitation of the people. Like all Russian socialists, the narodovol’tsy argued that European law only benefited exploiters. They knew that usually the bourgeoisie overthrew absolute monarchies in European countries, and they did not want to see this repeated in Russia.

Soon before his assassination, Alexander II had agreed to allow representatives of local self-governments to participate in discussion of proposed legislation – basically bringing members of the public into the State Council that drafted and enacted legislation. The role of members of local self-governments would be only consultative, but this bold step could have eventually led to the granting of a constitution. The assassination buried this chance. Alexander III rejected his father’s plans and announced that he would rule as an autocrat – a promise that he kept until his death in 1894. His son Nicholas II was even more insistent on ruling on an autocrat.

As former Hungarian communist Tibor Szamuely noted: « “Narodnaya Volya” destroyed itself by achieving its supreme triumph. Its history is usually referred to as a glorious failure. What had it gained for the Russian people? Nothing. It had merely frittered away its members’ lives in acts of individual terrorism that were inevitably doomed to failure. Such is the conventional view. It is wrong. In terms of its own purposes “Narodnaya Volya” was completely successful. It had sacrificed itself on the blood-stained altar of revolution, but in death it was triumphant. The revolution had won the race for time. The main aim had been accomplished: Russia’s constitutional bourgeois development had been stopped. It was only resumed twenty-five years later, and by then it was too late».

The Manifesto of October 17, 1905 granted political freedom and a State Duma. However, Nicholas II believed that he had signed the manifesto under stress and that he was always free to revoke it. Many members of the government and political movements from right to left also rejected this attempt to turn Russia from an autocratic state into a semi-autocratic/semi-constitutional state that would have drawn it closer to European countries. This rejection of European liberal statehood was unprecedented in the history of European revolutions. The People’s Will, in the long run, obtained a major victory in ensuring that the Russian Empire would never become a European liberal state. While many Europeans were becoming disillusioned with liberalism, the People’s Will and other revolutionary movements fought to make sure that people in Russia would never have the chance to become disillusioned with liberalism.

Other Major Successes of the People’s Will

Revolutionaries continually attempted to restore the People’s Will right up to the death of Tsar Alexander III even though all these attempts failed. American historian Norman Naimark attempted to explain why revolutionaries during the reign of Alexander III could not and would not break with the legacy of the People’s Will. Orthodox populists and Marxists could not really offer an alternative because the People’s Will, during its “heroic” phase from 1879-1881, was the only party that had come closest to toppling the government [4, p. 90] The very name “People’s Will” evoked strength and daring. No self-admitting revolutionary could reject the legacy of the People’s Will since that organization had accomplished so much for the revolutionary cause as well as furnishing the cause with martyrs. In fact, the assassination of Tsar Alexander II demonstrated to all future revolutionaries that retreat was impossible.

Other major successes of the People’s Will included:

- Mobilizing members of the intelligentsia, students, women, officers, workers, members of ethnic and religious minorities to join its satellite organizations.

- Conducting an international information war against the government and winning the support of public opinion in Europe and the United States. The Narodovol’tsy convinced many Europeans and Americans that, in Russian conditions, terrorism was a completely legitimate means of struggle for political freedom. Many luminaries of world literature admired the People’s Will.

- Shaping the attitudes of liberals and conservatives toward terrorism. Liberals often supported left-wing terrorism in hopes that the government would grant concessions. The activity of the People’s Will gave birth to the loyalist Sacred Brotherhood which marked the prehistory of right-wing terrorism in Russia and Europe. Liberals supported socialist terrorists in the early 20th Many reactionaries and conservatives took an ambivalent attitude toward terrorism and often withheld their support from the government. In the long run, the People’s Will made a major contribution to the shrinking of the government’s base of supporters in educated society.

The Triumph of Revolutionary Conspiracy and Mystification

In many ways, the People’s Will represented the high point of the tradition of European secret political societies. The Narodovol’tsy directed much attention to building a hierarchical Executive Committee linked to its satellite organizations. However, the People’s Will took elements of revolutionary mystification and deceit to new levels, especially in applying certain parts of the notorious Catechism of the Revolutionary co-authored by S. G. Nechaev and M. A. Bakunin in 1869. Elements of revolutionary mystification and deceit used by the Peoples’ Will included:

- misleading self-identification: members of the Executive Committee always described themselves to fellow party members, outsiders, officials (especially at trials) as agents of the third degree of the Executive Committee: They conveyed the impression that the Executive Committee was an all-powerful force that the police would never catch.

- manipulating supporters: the Executive Committee set up organizations to work among other socialists, liberals, the intelligentsia, workers, students, officers, religious sectarians, non-Russians. What members of the Executive Committee said to one audience was not the same as what it said to another. They told liberals that they had common interests and should work together for a constitution but never told liberals that their agenda included the establishment of a socialist society. Non-Russians were told that the People’s Will favoured the break-up of the Empire while the organization did not dare alienate Russian supporters with calls for the break-up of the empire.

- dissimulation in political trials: members of the People’s Will at trials never told the court that they were socialists. Instead, they maintained that they were merely fighting for political freedom and had been forced to take up terrorism because of government repression.

- manipulating foreign public opinion; telling Europeans and North Americans that the People’s Will was an organization of freedom-fighters who had been forced to take up terrorism because of persecution from an evil government and that they merely wanted the same political freedoms that Europeans and North Americans had.

- De-emphasizing terrorism: members of the Executive Committee stated that assassination of the tsar was only one of their tactics in changing Russia and that tactics could always be revised. In practice, the assassination of Alexander II absorbed the personal and financial resources of the Executive Committee.

All of this suggests that the People’s Will took the tactics of conspiratorial mystification and deceit to new levels in Europe. In fact, the use of a hierarchal conspiracy with satellite organizations foreshadowed the practices of terrorist organizations in Europe and the rest of the world in the 20th and 21st centuries.

The darkest chapter in the history of the People’s Will was how some members supported and encouraged anti-Jewish pogroms in 1881-1882. This marked a landmark in the history of left-wing antisemitism.

The Central Moment in Russian Political Terrorism

Historians still try to << divorce>> the People’s Will from the terrorists of the 1860s and the early 20th century largely by emphasizing the high moral principles of the Narodovol’tsy. However, this is an act of historical mythmaking. The People’s Will was the organic link between all stages of terrorism in Russia.

American historian Adam Ulam described terrorists of the 1860s such as D.V. Karakozov, N.A. Ishutin, I.A. Khudiakov, and S.G. Nechaev as psychopaths motivated by a sheer passion for violence. By contrast, members of the People’s Will were motivated by a sincere belief that terrorism was a legitimate form of struggle against a repressive government even though Ulam admitted that there were morally repugnant incidents in the history of the People’s Will. Ulam noted that the narodovol’tsy acknowledged Karakozov and Nechaev as their predecessors rather than distance themselves from the terrorists of the 1860s. However, he emphasized that this acceptance of the legacy of the past formed part of a broader accceptance by Russian socialists and liberals from the late 1870s to early 1900s of using terrorism as a legitimate means of political struggle.

American historian Anna Geifman argued that the terrorists from 1900-1917, particularly anarchists and members of obscure extremist groups, can best be described as terrorists of a new type. Unlike their predecessors in the 19th century, the new terrorists were less ideologically oriented, less scrupulous about means, and less restrained in their choice of targets. The terrorists of the 20th century had a long tradition preceding them just as the People’s Will had traditions set by the terrorists of the late 1860s. Despite Geifman’s assertions that the terrorists of the 20th century attracted many common criminals, psychologically unstable people, teenagers, and children, the fact remains that the terrorists of the 19th century included many morally reprehensible people, including those who were psychologically unstable, and there was an involvement by common criminals in revolutionary movements even in the 1870s and 1880s. The high-minded terrorists of the People’s Will not only practiced deceit and mystification in dealing with liberals and fellow socialists, but also crossed moral boundaries by killing Alexander II. Old narodovol’tsy would have been the first to notice a change in the next generation of terrorists and their practices, but they apparently did not detect any difference. Many veteran populists and members of the People’s Will joined the Party of Socialists-Revolutionaries, especially its Battle Organization. The only differences between the two waves of terrorism were the sheer magnitude of the second wave and the large numbers of parties and movements participating in it. One simply cannot separate the People’s Will from other waves of terrorism in Russia.

Despite all its failures and dark sides, the People’s Will still occupies a special place in the history of terrorism in the Russian Empire, Europe, and the rest of the world. In fact, it scored more victories than defeats even if it did not overthrow the government. The People’s Will in so many ways foreshadowed many future trends in terrorism in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Citations

- Рокки Тони. Идеологическое и тактическое оружие организации «Народной воли»: как народовольцы стали легендарными в истории терроризма (The ideological and tactical weapons of the People’s Will organization: how the narodovol’tsy became legendary in the history of terrorism). // Сборник материалов VIII Международной научно-практической конференции. 7–9 октября 2020 г. Тула-2021, с. 421-432.

- Leroy-Beaulieu, Anatole. «The Empire of the Tsars and the Russians». 3 vol. Translated from the third French edition with annotations by Zenaide A.Ragozin. New York: G.P.Putnam’s Sons, 1893-1896. Part I. The Country and its Inhabitants. Part II. The Institutions Part III. The Religion

- Szamuely, Tibor. The Russian Tradition. London: Secker & Warburg, 1974.

- Naimark Norman.M. Terrorists and social democrats: the Russian revolutionary movement under Alexander III. Cambridge MA and London: Harvard University Press, 1983.

- Ulam, Adam B. In the name of the people: prophets and conspirators in pre-revolutionary Russia. New York: Viking Press, 1977.

- Geifman, Anna. Thou shalt kill: revolutionary terrorism in Russia, 1894-1917. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993.Русский перевод в электронной форме. Гейфман, Анна. Революционный террор в России, 1894— 1917. Москва: КРОН-ПРЕСС, 1997.