“Where does all this madness about hara-kiri, bushido come from…” /From one Russian radio broadcast./

“… We must win honestly,

We must live in the bright light,

They will compose songs about us,

Heaven will be hot…”

“Sport Heroes”

“…Who knows what awaits us?

Who knows what will happen?

And will be strong

And it will be mean.

And death will come

And condemned to death;

No need

Plunge your eyes into the future.”

G. Apollinaire (Translated by M. Kudinov)

You ask today — it seems to many that this cruel tradition is gone forever, remained in the 19th century, you can forget about it, but this is far from the case…

For example, quite recently, in 2001, the Olympic gold medalist, judoist Inokuma Isao, committed seppuku. Most likely due to the fact that his construction company was close to ruin. What made him commit suicide in such a painful way? Can we understand?

Probably, we, first of all, should talk about what it is and why the Japanese chose it as one of the methods of suicide.

First, let’s look at what “seppuku” is and what “hara-kiri” is. The hieroglyphs, it seems, are the same, but “Seppuku” sounds nobler, in the Chinese manner. Thus, it is usually understood as ritual suicide, committed according to the Bushido code. “Hara-kiri” is the word used by commoners, it is more everyday. We will see the difference in their use a little later, using the example of the terrible suicide of the wonderful writer Mishima Yukio.

How exactly was seppuku done?

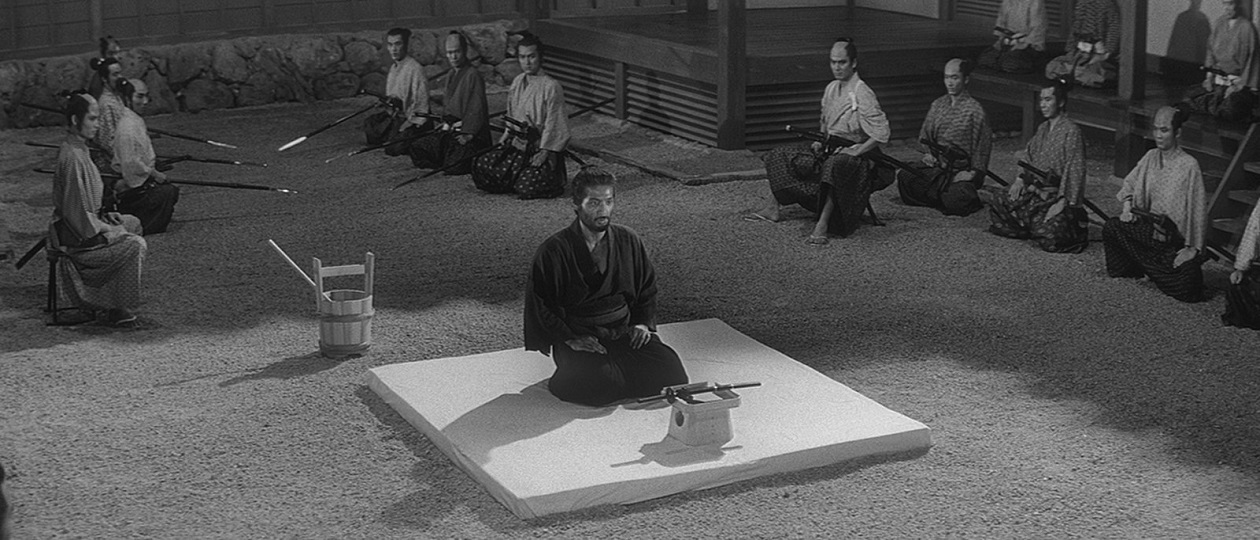

In accordance with the code, shortly before the ceremony itself, the appointment of persons responsible for conducting the procedure for opening the abdomen and for presence at the same time took place.

A place was also chosen for the performance of the rite, which was determined depending on the official, official and social status of the sentenced. The shogun’s associates performed seppuku in the palace, the lower-ranking samurai in the garden of the prince’s house, to whose care the convict was given. Sometimes it was performed in the temple. For example, officials used this opportunity if the order to make seppuku came during their journey. This explains the fact that each traveling samurai has a special dress for such an occasion.

For the ritual, which took place in the garden, a fence was built from stakes with cloth stretched over them. The fenced area should have been approximately 12 square meters if the seppuku was performed by an important person.

There were two entrances in the fence: the northern one — “umbammon” and the southern one — “shugi-yomon” (“eternal door”). (In some cases, the fence was made without doors at all, which was more convenient for witnesses who watched what was happening inside.) The floor in the fenced space was covered with mats with white borders, on which a strip of white silk or white felt was laid. Here, too, they sometimes arranged a kind of gate made of bamboo wrapped in white silk, which looked like temple gates; they hung flags with sayings from sacred books, lit candles if the ceremony was performed at night, etc.

On the eve of the performance of the rite, if the convict was allowed to make seppuku in his own house, the samurai invited close friends to his place, drank sake with them, ate spices, joked about the fragility of earthly happiness, thereby emphasizing that he was not afraid to die … Before his death they wrote haiku.

Now the procedure itself.

The incision was made from left to right, especially persistent ones made another one – from the chest to the navel.

In most cases, there was an assistant — kaishaku, whose task was to cut off the head. This role was usually played by a relative, friend, or some other trusted and respected samurai.

The fact is that the participation of the assistant was also clearly regulated. First, he moistened the blade of the katana with clean water, then slowly drew his sword at the face of the man to commit suicide, letting him know that he was ready to fulfill his duties, and then he took up a position convenient for striking from the side and from behind.

The task was very difficult. It was necessary, on the one hand, to give the man committing suicide an opportunity to demonstrate courage and composure, and on the other hand, to immediately stop the torment as soon as he gave the signal. In addition, it was necessary to cut off the head so that it did not fly off the shoulders and did not roll on the floor, which was considered indecent, but remained hanging on a piece of skin …

After seppuku, the witnesses went to the house, where the owner offered them tea and sweets.

In samurai families, both boys and girls were taught how to perform seppuku correctly.

True, women did not do “seppuku”, but “jigai”, the essence of which is to cut the throat with one sharp movement.

It was performed with a special dagger (“kaiken”), which was a husband’s wedding gift, or with a short sword given to each samurai daughter during the rite of passage of age.

Before the ritual, the woman herself tied her legs, pulling her ankles to her hips. This was done so that convulsions would not interfere with dying in a beautiful and dignified pose.

Seppuku may have been performed as a show of remorse for a misdeed or crime. On the other hand, it also had a different meaning: the exposure of one’s soul and evidence that there was no secret intent in a person’s actions. They also resorted to it as a sign of protest, or disagreement with the accusations.

Such a suicide usually saved the samurai family from shame and from possible persecution by the authorities, which, of course, was also extremely important.

Now the question arises — why does Japan have such an attitude towards death.

Let’s remember what this country is like. Difficult soil for cultivation, earthquakes, typhoons, volcanic eruptions.

Just 128 kilometers from Tokyo, for example, there is the island of Miyakejima with an active volcano that erupts every few years. The last major eruption occurred on July 14, 2000. During eruptions and earthquakes, the island is shrouded in ash clouds that reach 18 km in height. But even more deadly is the poisonous sulfuric gas that seeps there from the bowels of the earth.

For security reasons, sensors for the content of toxic substances in the air are placed throughout the island. When the level rises, whether day or night, during work or at the height of the holiday, the inhabitants of the island immediately put on gas masks that they carry with them around the clock.

For many years I have been trying to understand, asking, but not getting an answer: why in Tokyo no one is preparing for a snowfall. “They don’t happen very often with us,” they tell me. But it happens almost every year!

In the end, I realized that the feeling of nature for the Japanese is, first of all, frailty and rebirth, which are manifested in the change of seasons and the cycle of existence. Flowers bloom in spring, leaves fall in autumn, piercing wind blows from the sea in winter. But with the advent of the new year, spring comes again. Cloudy, rainy days alternate with clear ones and this gives strength to live on. From here comes a hardy, calm and gentle attitude towards adversity, and when death comes, it is accepted calmly, as a return to the earth, as a reunion with nature.

In this general mood of humility before the elements and adaptation to nature, there is something from Buddhism with its concept of the frailty of things: there is nothing eternal in this world, everything that has a form will certainly collapse. Every person will die someday.

No, the samurai despised not life, but death. They were living people and, like all of us, rejoiced and appreciated her priceless moments. However, in the first place for them was honor, and it was the honor that was dearer to them than all earthly goods.

Life is fleeting and transitory. Sooner or later, the moment will come when we leave this mortal world. What matters is what we leave behind, what kind of memory …

For example, one case is still not forgotten when assassins killed the wrong samurai by mistake. His seven-year-old son allegedly identified the body, and as proof he ripped open his stomach and saved his father’s life at such a cost: the killers, who believed in the deception, left, considering their work done.

In the book Bushido: The Soul of Japan, Inazo Nitobe writes: “Two brothers, Sakon and Nike, who were twenty-four and seventeen years old respectively, attempted to kill Ieyasu in order to avenge their unjustly slandered father. They infiltrated his camp, but were captured. The old general, admiring their courage, decided to honor them and let them die a noble death by committing seppuku. Their brother Hatimaro, a boy of 8, was also obliged to share their fate, since the sentence was passed on all the men in their family, and the three brothers were escorted to the monastery, where the execution was to take place. To this day, the diary of a doctor who was present at the time and described the following scene has been preserved:

“When the preparatory part of the ceremony was completed and the brothers sat down on the mat for the last part of the execution, Sakon turned to the youngest brother and said: “Start first — I want to make sure you did everything right.” But the boy replied that since he had never seen seppuku performed, he would first like to see how the brothers would do it so as not to disgrace the family. The older brothers smiled through their tears, “Well said, little brother! You can be proud that you are a worthy son of your father!” and seated little Hatimaro between them. Sakon was the first to thrust his sword into his stomach and said: “Look! Do you get it now? Just don’t stick the blade in too deep or you might lean back. Lean forward and keep your knees firmly on the floor. Then Naiki, in turn, repeated the actions of his older brother and explained to the boy: “Keep your eyes open, otherwise you will look like a dying woman. If the dagger gets stuck inside, take courage and try to redouble your efforts to drive it to the right.” The boy carefully looked first at one, then at the other, and when they expired, he diligently and worthily repeated everything they taught him, almost cutting himself in half. ”

During the Sengoku period, there was a samurai, Muneharu Shimizu, who was ordered to do himself a seppuku. In the evening, before the ceremony, one of his servants, a man named Sirai, asked him to come to him. Although Shimizu was not up to it, he could not refuse his faithful servant. When he came to his house, he was led into a room and seated on the tatami opposite Shirai. At first, he spoke about the frailty of the world, about the fact that one should not be afraid of death. Suddenly he coughed and swayed. Opening the kimano, he showed his master a cut across the abdomen: “When I heard that you were coming, I made myself a seppuku. I wanted to show you that it’s not that hard at all.”

Shimizu didn’t know how to thank the servant. He got up, took out his sword, and, wiping away his tears, cut off his head. After standing for several minutes over a lifeless body, strengthened by the spirit, he set off towards his death.

Or here’s another. Yoshiteru Murakami, in order to save his master, Prince Morinaga, climbed onto the roof of the house in which they were hiding, and which was surrounded by enemies. He set fire to the roof and shouted: “Dogs! I am Prince Morinaga! Look! I’ll show you cowards how a real warrior dies!”

Glancing back, he saw his master disappear into the darkness while all eyes were fixed on the roof. Turning back, Yoshiteru exposed his stomach and cut it deeply. Despite the pain, he stood straight and his face remained calm. Picking up the spilled intestines, he cut them and threw them down into the faces of the enemies. Then, he put the sword in his mouth and rushed down…

Perhaps enough graphics … Although these are all stories on which more than one generation of Japanese has grown up …

Let’s still return to the original question — the difference between seppuku and hara-kiri.

On November 25, 1970, Mishima Yukio, one of the most famous writers of the twentieth century, led four young cadets from his personal army, the Shield Society, to a meeting with a general of the Japan Self-Defense Forces.

The one who expected nothing more than the usual pleasant interaction was stunned when he was grabbed, bound and gagged, threatening to kill him if he did not immediately call all the base personnel. Mishima prepared for them a call to revolt against the Americans. After a series of scuffles with officers who were trying to break into the room, the writer went out onto a wide balcony and spoke to about a thousand military men who had gathered on the parade ground.

Mishima urged them on the need for constitutional reform, emphasizing that the “Peaceful Constitution” did not even recognize the very fact of their existence. He was going to perform for half an hour, but he was met with indignation — they shouted to him: “Crazy!”, “Idiot!”, “There is peace in Japan!”, “Go down!”, “Shut up!” …

He gave up after seven minutes, and went back to the office, where he began to methodically prepare for ritual suicide. Inserting the short sword deep into his stomach, Mishima painfully cut it, after which his student assistant Morita Masakatsu attempted to decapitate him.

Unfortunately, Morita was not good with a sword and was very worried, so over and over again he could not hit the neck, striking on the shoulders. Then another cadet came to the rescue, who finally cut off the unfortunate Yukio’s head, which rolled into a corner (see below).

Morita himself, repenting that he could not properly fulfill his duty, also cut his stomach open and was beheaded.

Since the procedure was not performed properly, most Japanese talk about Yukio Mishima’s “hara-kiri”. If everything worked out the way he planned, it would be “seppuku”.

The Japanese themselves do not have a common opinion about this tradition today, but one thing is certain — in their mentality it has played and continues to play one of the most important roles.