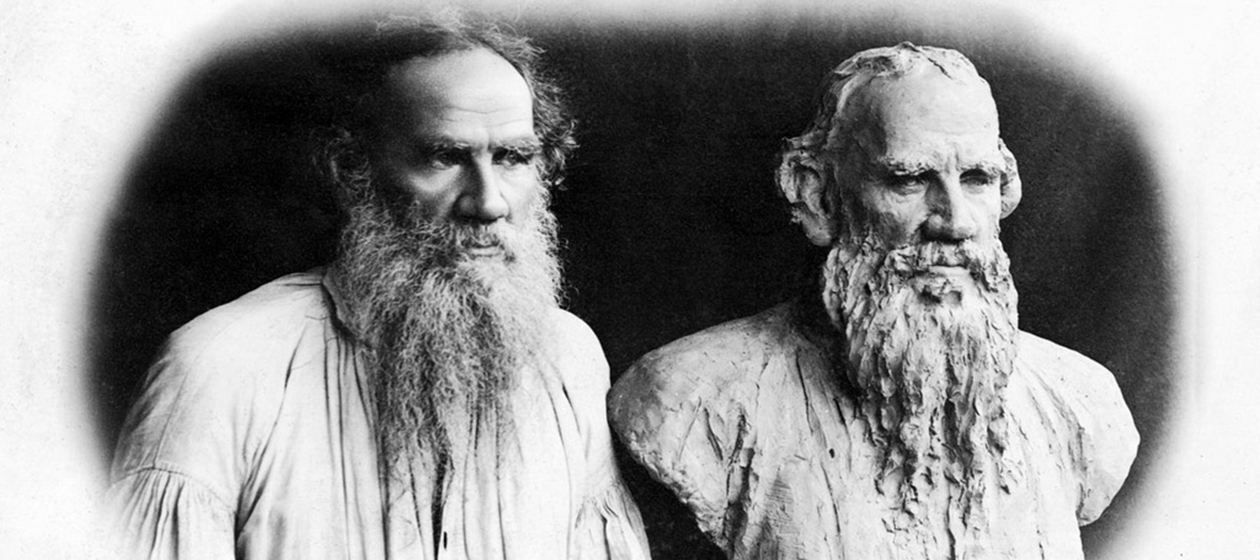

Leo Tolstoy, the world’s greatest writer, is often glorified as the apostle of non-violent resistance to evil. Tolstoy has been hailed as a Christian anarchist who inspired the heroism of Mahatma Gandhi and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

As noted in the previous article, Tolstoy exonerated terrorists and revolutionaries in his letter “I Cannot Be Silent” in 1908.

Tolstoy was a man of contradictions who puzzled many people.

Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin called Tolstoy “the mirror of the Russian revolution” because he incarnated the contradictory and unstable nature of the peasant masses during the Revolution of 1905-1907. As Lenin wrote in 1908:

“The contradictions in Tolstoy’s works, views, doctrines, in his school, are indeed glaring.

On the one hand, we have the great artist, the genius who has not only drawn incomparable pictures of Russian life but has made first-class contributions to world literature. On the other hand, we have the landlord obsessed with Christ.

On the one hand, the remarkably powerful, forthright and sincere protest against social falsehood and hypocrisy; and on the other, the “Tolstoyan”, i.e., the jaded, hysterical sniveller called the Russian intellectual, who publicly beats his breast and wails: “I am a bad wicked man, but I am practicing moral self-perfection; I don’t eat meat anymore, I now eat rice cutlets.”

On the one hand, merciless criticism of capitalist exploitation, exposure of government outrages, the farcical courts and the state administration, and unmasking of the profound contradictions between the growth of wealth and achievements of civilization and the growth of poverty, degradation and misery among the working masses. On the other, the crackpot preaching of submission, “resist not evil” with violence.

On the one hand, the most sober realism, the tearing away of all and sundry masks; on the other, the preaching of one of the most odious things on earth, namely, religion, the striving to replace officially appointed priests by priests who will serve from moral conviction, i. e., to cultivate the most refined and, therefore, particularly disgusting clericalism.”. [1]

Lenin missed the whole point about Tolstoy because he could only see the great writer as a representative of the peasantry, scorned by Marxists as an unreliable petty-bourgeois ally of the working class. The roots of Tolstoy’s contractions were far deeper and went back decades.

Tolstoy hated the nihilists and other “New People” of the 1860s for insisting that literature should serve the liberation movement and devote itself to condemning political and social injustice. The writer of War and Peace and Anna Karenina proclaimed that literature should celebrate life in all its forms.

But, if a nihilist is one who denies the legitimacy of institutions and traditions, then Tolstoy possibly became the biggest nihilist in the Russian Empire because he denied any legitimacy of the government, court system, Russian Orthodox Church, and other institutions.

In his own way, Tolstoy founded his own religion of moral self-perfection and non-violent resistance to evil. He has been called a Christian anarchist, but one must ask what type of Christianity did Tolstoy proclaim?

I suggest that the Christianity of Tolstoy was a form of Gnosticism, one of the oldest heresies in the history of Christianity. Gnosticism and similar heresies urged their followers to see themselves as a self-perfected elite whose souls had merged with God — and, once, one’s soul had merged with God, one could no longer sin because one was perfect. Gnosticism proclaimed that its followers could attain a higher level of spiritual consciousness, far above the consciousness of ordinary Christians.

Followers of Gnostic and similar heresies tended to hate the surrounding world as evil and that they were morally superior to people who live in this world. Tolstoy was no exception to these beliefs, and he used his considerable talent to express his hatred of the world in which he lived — the Russian Empire — and to make sure that others knew just how much he hated this world and why he and others were morally superior to it.

Nobody delegitimized the Russian government and society the way Tolstoy did in his novel Resurrection, published in 1899, the year of Empire-wide student riots. While he did not commit any illegal acts against the government, Tolstoy condoned the destructive mentality and actions of the revolutionary intelligentsia.

Historians have usually mentioned Tolstoy’s involvement with terrorism by mentioning his plea to Tsar Alexander III in March 1881 to pardon the five accused assassins of his father Alexander II. Rather than continuing bloodshed, argued Tolstoy, Alexander III could put a stop to the cycle of violence by pardoning the five regicides and exiling them from Russia. This would demonstrate that Alexander III had incarnated the teaching of Jesus Christ to forgive one’s enemies. Alexander III disregarded Tolstoy’s plea and the five assassins were hanged.

However, a tsar and the intelligentsia had not heard the last from Tolstoy about what was causing violence in the Russian Empire and who was the real guilty party. Tolstoy revealed his thoughts about “the system” in Resurrection.

This novel is a colossal attack upon the government, bureaucracy, Russian Orthodox Church, the armed forces, the propertied classes, public morality, the family, and marriage. No aspect of Russian life is spared by Tolstoy — the man who once proclaimed that the purpose of literature is to celebrate life in all its forms. Not even an ancient Gnostic could have expressed hatred of the surrounding world in the way that Tolstoy did.

The novel’s hero Dmitri Nekhlyudov journeys through the criminal and revolutionary worlds of Russia and concludes that the government, the Russian Orthodox Church, the system of private property, morality, and other institutions are the real criminals guilty of perverting people. As Sergei Nechaev divided officialdom and educated society into six categories, depending upon their usefulness to the revolutionary cause, so Nekhlyudov divided the criminal world into five categories and showed how they were all victims of society.

“The first were perfectly innocent people, victims of judicial blunders.

The second class consisted of people condemned for actions in exclusive circumstances: passion, jealousy, or drunkenness; circumstances in which those who judged them would surely have committed the same actions.

The third class consisted of people for having committed actions which, according to their own ideas, were quite natural and even good, but which those other people, the men who made the laws, considered to be crimes. Such were those who sold spirits without a license, smugglers, those who trampled the grass and felled trees for firewood on large private estates and in the forests belonging to the Crown, the mountain-dwelling robbers, and those who robbed churches.

To the fourth class belonged those who were imprisoned only because they stood morally higher than the average level of society. Such were the sectarians; such were the Poles and the Circassians, rebelling in order to regain their independence; such were the political prisoners, the Socialists, and the strikers.

The fifth class consisted of persons who were far more sinned against than sinning in their relations with society. These were the castaways, stupefied by continual oppression and temptation… The conditions under which they lived seemed to lead on systematically to those actions which are termed crimes…to this class also he assigned those depraved, demoralized creatures, whom the new school of criminology classified as the criminal type, the existence of which was considered to be the chief proof of the necessity for criminal law and punishment. These so-called demoralized, depraved, abnormal types were in Nekhlyudov’s opinion, no other than the same people against whom society had sinned, only here society had sinned not directly against them, but against their parents and forefathers.” [2, pp. 346-348]

Tolstoy proclaimed that common criminals and revolutionaries were not at fault because they were the products and victims of an evil society. In fact, revolutionaries and other outlaws had a higher morality than their persecutors. But what did Tolstoy propose as the solution? He proclaimed that people must seek the kingdom of heaven within themselves and win over other people by their examples. This was not what the revolutionaries wanted to hear. One suspects that many leftists took what they liked about Tolstoy’s description of the revolutionary and criminal worlds and used it to justify revolutionary and terrorist activities.

In Resurrection, Tolstoy condemned the entire system and sentenced it to death. Tolstoy delegitimized government, society, and all other institutions, and the terrorists and revolutionaries soon began bringing the whole thing down. And Tolstoy was ready in a few more years to further exonerate those who were trying to destroy the world that he hated. I Cannot Be Silent is the logical conclusion of Tolstoy’s previous thoughts on the legitimacy of the structure of the Russian Empire.

Sources Used

- Lenin, V. I. Leo Tolstoy as the mirror of the Russian Revolution https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1908/sep/11.htm

- Tolstoy, Leo. Resurrection. Trans. Louise and Aylmer Maude. Moscow: Raduga Publishers, 1990.

One comment

Natalia R

14.02.2025 at 15:31

What a thoughtful, complex and comprehensive analysis of one of the greatest minds of the 20th century. Tolstoy has been considered one of the most influential thinkers in history, so it’s a great pleasure to read your investigation into his life and philosophy. Makes me want to pick up his “Resurrection”. Thank you