Every European revolution had a counter-revolution. Russia in 1917 was a huge exception to this historical pattern because there was no counter-revolution in the former Russian Empire between the February and October Revolutions of 1917. In fact, the conditions for a counter-revolution were completely absent.

Russian revolutionaries prided themselves on their understanding of revolutions of the past, particularly the French Revolution of 1789-1799, the revolutions of 1830 and 1848-1851 in France, and the uprising of the Paris Commune in 1871. The speediness of the February Revolution with the downfall of Tsar Nicholas II left most socialists, including Bolsheviks, fearful that counter-revolutionary forces still presented a mortal threat to the revolution. Too many socialists concluded that the Russian Revolution was doomed to experience the same trends that destroyed the French Revolution. These trends included:

1. The peasantry, once it had received land, would turn counterrevolutionary.

2. Entire areas of the country, especially the Don, Kuban, and other Cossack territories, would turn into a Vendee—the French department that witnessed a counter-revolutionary uprising in 1793 of royalist peasants led by aristocrats and priests and became a generic term for mass counter-revolution by the lower classes.

3. A flight by Tsar Nicholas II and his family, just like the failed flight by French King Louis XVI and his family to Varennes. Many Russian socialists firmly believed that Tsar Nicholas, just like Louis XVI, would flee to return at the head of a counter-revolution.

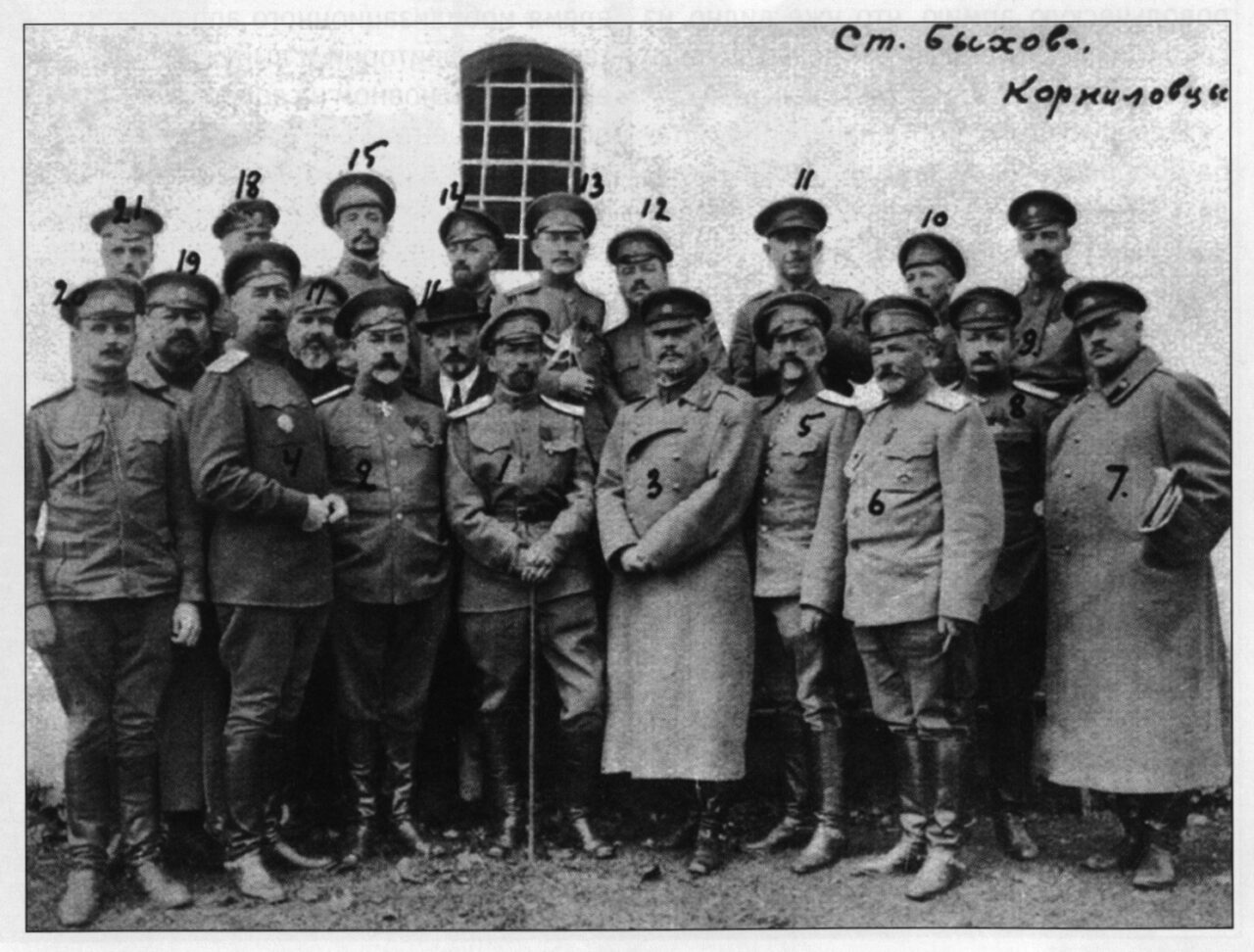

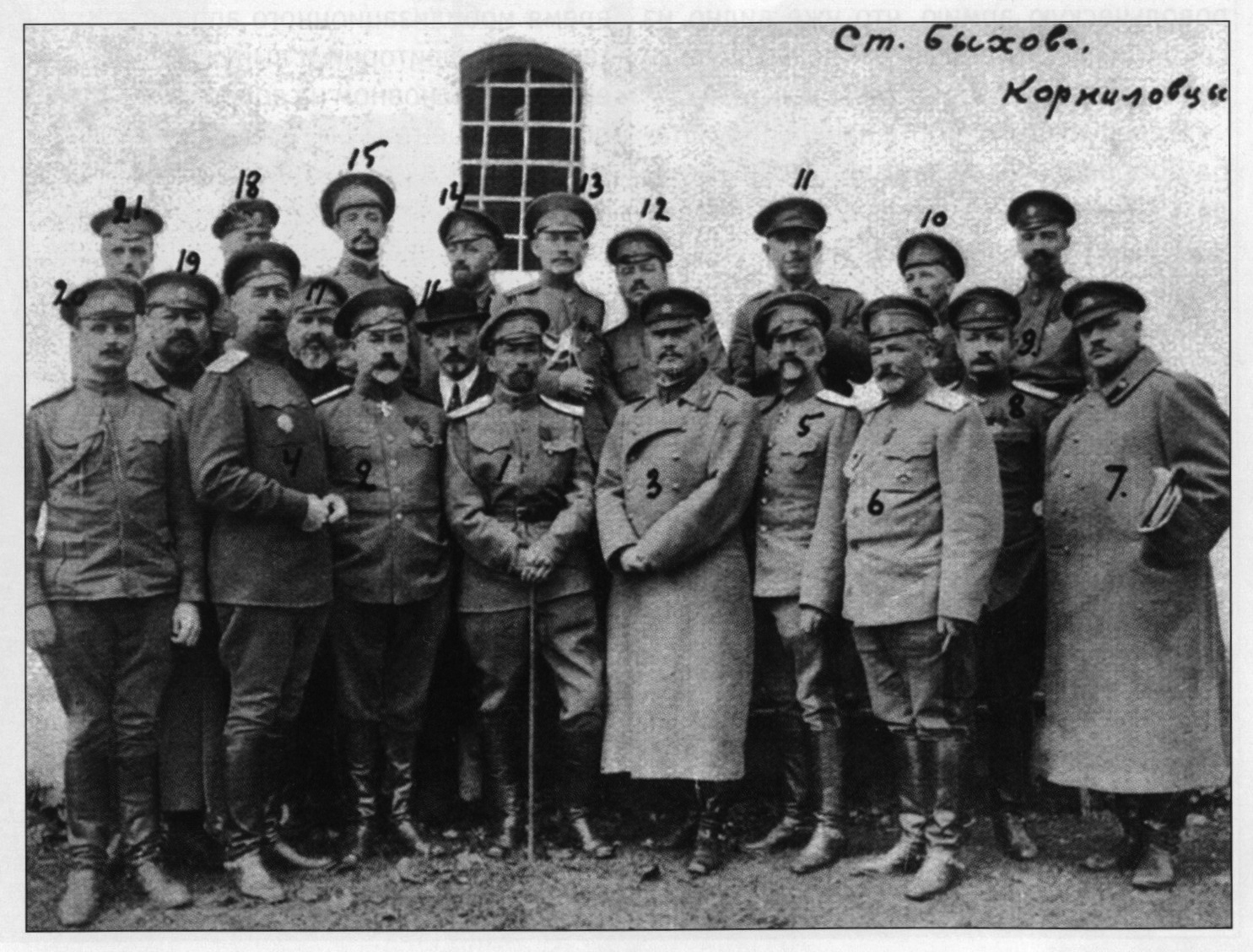

4. А military coup (seizure of power) led by a man on a white horse who would crush the revolution and rule like Napoleon Bonaparte or Napoleon III. Not surprisingly, many Russian socialists regarded General Lavr Kornilov, the commander-in-chief, as the Russian equivalent of Napoleon.

However, Russia in 1917 was not France in 1789. The peasantry did not turn counter-revolutionary after it seized lands from nobles and other private landowners. Peasants fought both Reds and Whites during the Civil War. General Kornilov lacked the intelligence and leadership skills to become a Napoleon. It is true that the Cossack areas turned into areas of mass anti-Bolshevik movements after the October Revolution. However, the relationship between Cossacks and the White armies was never firm because Cossacks and White army leaders had conflicting goals and tactics. Calling the Don, Kuban, and other Cossack territories a Russian version of the Vendee is simply inaccurate.

The misreading of the French Revolution and making false parallels with the Russian Revolution continued well into the 1930s with many Communists believing that the New Economic Policy, introduced in 1921, represented the Thermidor of the Russian Revolution—meaning that just as the overthrow of Maximilien Robespierre on 9 Thermidor Year II (July 27, 1794) ushered in the triumph of moderate and reactionary forces, so did the New Economic Policy represent a surrender to capitalism. Just as General Kornilov had been accused in 1917 of being a Russian Bonaparte, Leon Trotsky, as war commissar, was accused by many Communists, especially followers of Joseph Stalin, of Bonapartist ambitions and of plotting a military takeover. Many followers of Trotsky accused Stalin of being the Bonaparte of the Russian Revolution–meaning that just as Napoleon betrayed the French Revolution, Stalin betrayed the Russian Revolution.

Russian revolutionaries apparently had forgotten what Karl Marx said about revolutionaries who tried to make history happen exactly as it had in the past.

“Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce. People make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the minds of the living. And just as they seem to be occupied with revolutionizing themselves and things, creating something that did not exist before, precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes in order to present this new scene in world history in time-honored disguise and borrowed language. “[1]

Although the French Revolution of 1789-1799 and Russian Revolution of 1917-1922 had many grounds of similarity, certain tendencies in the French Revolution simply did not repeat themselves in the Russian Revolution.

No counter-revolution happened between the February and October Revolutions because a counter-revolution was impossible. There were many anti-revolutionary individuals and groups and the Constitutional Democratic Party (Kadets or Party of People’s Freedom) was certainly the biggest anti-socialist party in the country. But nobody in the former Russian Empire would have wanted to turn the clock back to the days of the autocratic Nicholas II. Several reasons account for this.

1. The Romanov dynasty had simply discredited itself particularly during the war. As the Soviet publicist Mark Kasvinov put it — they had reached that final limit in time and space beyond which there was not and could not be anything more for them. [2] If Nicholas II and his family had not been killed in 1918, the myth of the martyr tsar would have never emerged.

2. There was no mass base for a counter-revolution. Right-wing parties dissolved themselves or were banned after the February Revolution. The largest rightist party was the Union of the Russian People, organized in November 1905. The Union’s membership eventually topped 400,000 making it the largest political party in the Russian Empire and it was the largest legal party. The Union of the Russian People was the largest far right party in pre-1914 Europe. Its member organizations included patriotic leagues, parish brotherhoods, anti-revolutionary organizations, women’s groups, workers’ circles, student groups in post-secondary and secondary schools, peasant societies, etc Right-wing groups were generically called Black Hundreds — the name given to tax-paying merchants, artisans, and other urban residents in the 1600s — as opposed to White Hundreds — members of the nobility. On a more restricted level, Black Hundreds referred to members of fighting squads and participants in pogroms. The term Black Hundred eventually referred to anybody with a far-right mentality or who belonged to a far-right party or movement.

3. The Black Hundred parties and movements had never been a unified force long before 1917. They spent more time fighting each other than fighting liberals and socialists. The biggest social grouping in the Union of the Russian People were peasants in the western provinces of Kiev, Volyn and Podolia. They saw their major enemies as the Polish Roman Catholic landowners and hoped that the Tsar would give them the Polish-held lands. However, the hopes of these rightist revolutionaries (the peasants) were crushed because the government regarded landowners’ property rights as sacred regardless of the ethnicity or religion of the landowners. The February Revolution gave these rightist revolutionaries new hopes for attaining these lands and there can be no doubt that the Black Hundred peasant movements merged into the nation-wide peasant movements bent on seizing the lands of the nobility.

4. The conservative and reactionary parties were in no position to call for the restoration of the monarchy because they themselves had played their role in bringing down Nicholas II. Along with generals, aristocrats, and even members of the Imperial Family, the right-wing had denounced the tsar and his government in the Duma, discussed plans for a military seizure of power, and removing Nicholas from power. Since the highest levels of society had contributed to the downfall of the tsarist regime, they could not lead a counter-revolution.

5. There were many right-wing opponents of the Provisional Government and Petrograd Soviet and their policies and who were appalled by the rapid disintegration of state and society and wanted the restoration of law and order. However, right-wing groups and individuals could not be described as counterrevolutionaries because they did not call for the restoration of the monarchy and the old order. At best, they could be called anti-revolutionaries for opposing attempts to end the war, land seizures by peasants, factory seizures by workers, declarations of autonomy and independence by the ethnic minorities. Anti-revolutionary tendencies could span a wide spectrum.

6. One can talk about anti-revolutionary groupings in 1917 among landowners, business people, generals and officers, church circles, disenchanted liberals and socialists, former members of reactionary and conservative parties, former officials and police, etc. But there was simply no mass base for any anti-revolutionary movement. The Cossacks, who numbered in the millions in 1917, were resisting the seizures of their lands by non-Cossack Russian and Ukrainian peasants and ethnic minorities. However, they saw their problems as local — just as they did during the civil war — and would not have participated in a nation-wide counter-revolution or anti-socialist movement (which is why the Cossacks were such unreliable allies of the White armies after the October Revolution).

7. Far right populist politicians in Europe or North America appeal to “the little guy” — people hating big government, big companies, big unions, and anything and anybody seen as causing them misery. The former Russian Empire lacked the base for a movement of “little guys”; The concept of an allegedly mass loyal простонародье — “simple people” — was never more than a tsarist and right-wing fantasy.

8. However, the Black Hundred mentality persisted after the February Revolution and it was encouraged by newspapers, patriotic and Russian nationalist societies, informal groupings of officers, business owners, landowners, “public figures”. The absence of the Union of the Russian People and other mass parties and movements did not hamper the spreading of pogromist mentalities, blaming others for their misfortunes, and longing for revenge. Both “old” and “new” Black Hundreds could blame “the politicians” of all tendencies for having led Russia to a catastrophe. Most importantly, many anti-revolutionaries asked who alone was benefitting from all the turmoil and they concluded that the old enemy from 1905 was stronger than ever and causing more destruction. The stage was set for blaming the Jews for everything that went wrong in 1917, for causing the October Revolution, and for unleashing the horror of Bolshevism upon Russia. A wave of anti-Jewish massacres would rage through the civil war, the biggest slaughter of Jews in 20th century Europe until the Jewish Holocaust perpetrated by the Nazis.

9. After the October Revolution, counter-revolutionary tendencies rose among the military and civilian supporters of the White armies, but even counter-revolutionary tendencies could vary in degree of how much people wanted to and did restore the pre-1917 order in the areas occupied by the White armies. The Whites had nothing to offer as an alternative to Bolshevism. Telling people that they were fighting for the right of the Russian people to choose their own form of government was vague enough to allow the Bolsheviks to assert that the Whites wanted to return the monarchy. The great White slogan of “One Russia, Great, United, and Indivisible” could not appeal to the non-Russian peoples. The Kadets could not really lead any major anti-revolutionary or counter-revolutionary movement thanks to their limited social base. Furthermore, Kadets expected somebody else to do the actual fighting. Just as Kadets had relied on socialists before 1917 to extract concessions from the government, so from 1917 onwards did the Kadets expect somebody else to overthrow the Bolsheviks — be it the SRs and Mensheviks or the White armies or the Germans or the Allies.

10. Monarchism was never a mass cause during the revolution and civil war. White generals such as Anton Denikin, Aleksandr Kolchak, and Nikolai Yudenich never stated that they were fighting for the restoration of the Romanov dynasty. They merely stated publicly that they were fighting for the right of the Russian people to choose their own form of government. This approach was vague enough to allow some to think that the Whites were calling for the restoration of the monarchy. There were many open monarchists among the White officers, but monarchism lacked a mass base of support. The reign of Nicholas II had discredited the entire idea of monarchy and very few people would have supported the restoration of the Romanov dynasty. Monarchism became an openly proclaimed cause with mass support only in the emigration after the end of the civil war.

The Russian Revolution of 1917-1922 was truly unique among European revolutions because it never had a counter-revolution. The former Russian Empire simply lacked the conditions for mass counterrevolutionary movements.

References

- Marx, Karl. The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte 1852

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1852/18th-brumaire/

- Касвинов, М.К. Двадцать три ступени вниз. (Twenty-three steps downward) 3-издание, исправленное и дополненное. Москва: Мысль, 1989, с. 436.

One comment

Dmitry

13.09.2025 at 12:38

Interesting topic. Fascinating presentation of a large amount of factual material. In many ways I agree with the author’s conclusions, however, the assessment of the events of February and October 1917 as a single revolution confuses me a little. It seems more correct to consider these events as independent, sequential events. They are very different. But I fully agree with the author’s main idea that in Russia in 1917-1922 no ideology was formed against the Bolsheviks.