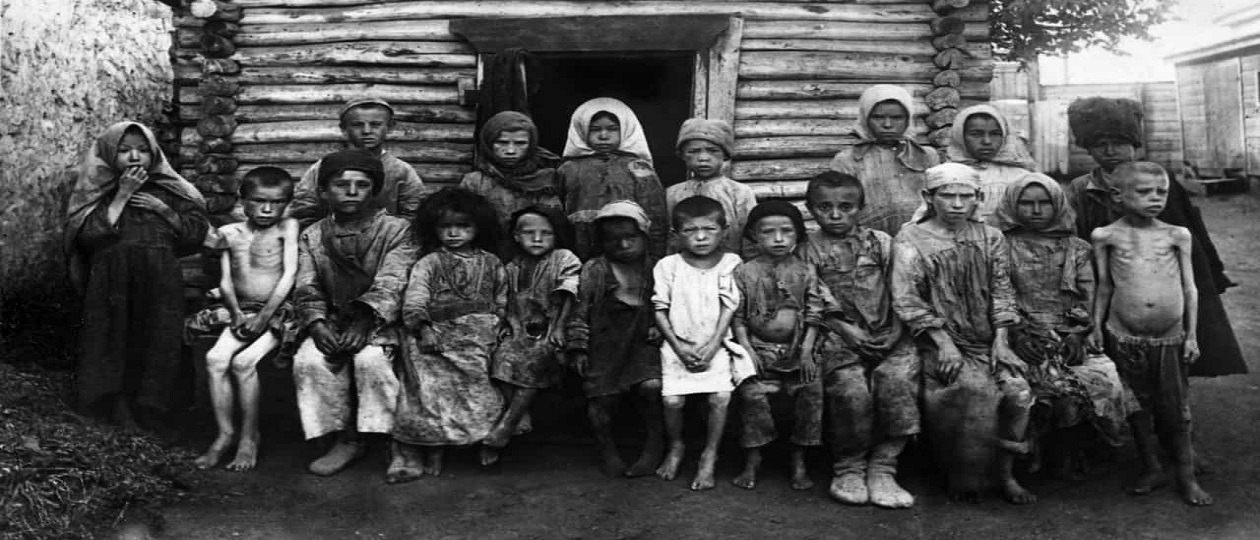

The famine of the early 1920s affected about 40 provinces of Soviet Russia.

In the summer of 1921, the ARA (American Relief Administration) and other international public organizations responded to the appeal of the RSFSR government for assistance.

The ARA staff (300 employees from America and about 10,000 from the local population) worked from September 28, 1921, to June 21, 1923, in 37 provinces affected by crop failures and famine, although the first ship carrying food arrived in Petrograd on September 1, and 120 kitchens were set up for 42,000 children in the first weeks of the month. By the end of 1921, 2,997 feeding stations in 191 cities and villages from St. Petersburg to Astrakhan served 568,020 children every day. In May 1922, the ARA fed 6,099,574 people, the American Quaker Society fed 265,000 people, the International Union for Children’s Aid fed 259,751 people, the Nansen Committee fed 138,000 people, the Swedish Red Cross fed 87,000 people, the German Red Cross fed 7,000 people, the British Trade Unions fed 92,000 people, and the International Labor Aid fed 78,011 people. During the ARA’s operation, 1,019,169,839 children’s meals and 795,765,480 adult meals were distributed. The calorie content of the children’s rations was 470 calories, while the adult rations had a calorie content of 614 calories. The food was provided to the population free of charge.

In addition to food assistance, according to the agreement signed on October 22, 1922, the ARA provided clothing, shoes, and other items to those in need. For example, the population was provided with 1,929,805 meters of fabric and 602,292 pairs of shoes. Medical assistance was provided to 1 million patients. In rural areas, the ARA provided the population with agricultural equipment and high-quality seeds.

The ARA deserves our gratitude for all of this. However, it should be noted that they were guided not only by humanitarian considerations: first of all, during the World War, the United States accumulated a huge amount of various supplies, which led to lower prices and posed a threat of a so-called overproduction crisis.

The management of American monopolies faced the urgent task of removing these goods from the national market. One of the solutions was to export them to countries in need of additional food supplies, including the Russian Federation. Secondly, the ARA employees were engaged in espionage activities.

Indeed, the ARA representatives were mostly former American military advisers of the Kolchak, Denikin, and Yudenich armies. Many of them fought against Soviet Russia with weapons in their hands. According to the Chekists’ operational data, “the personnel of the ARA employees who came from America were recruited with the participation of conservative and patriotic American clubs, under the influence of the former Russian consul Bakhmetyev, and filtered by a representative of American intelligence in England.

Most of the ARA employees had military experience. Some of them are still in the military and continue to receive salaries from the Ministry of War.” Among the American employees of the ARA, 20% were clerks and commercial employees, 15% were qualified economists and financiers (economic intelligence officers for major trusts and syndicates), and 65% were career officers (20% were high-ranking commanders and staff officers, 25% were military intelligence officers, and 20% were police officers).

Colonel William Haskell, who had once served as the High Commissioner in the Caucasus, was appointed director of the ARA’s representative office in the RSFSR. At that time, he was known for his uncompromising stance towards Soviet Russia and his efforts to create conflicts between Russia and Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. Later, after returning to the United States in 1923, he became one of the leaders of counterintelligence at the U.S. Army headquarters.

Kümler, Kernau, and Fink, members of the ARA’s staff, served in the American secret police. Another, Thorner, worked for British intelligence and, according to the GPU, was associated with Paul Dukes, a well-known British spy in Russia. Haskell’s assistants, Shafron and Gregg, served as advisors to the Polish army during the Soviet-Polish War of 1920, while Ferner, Boren, Havard, Fox, and Vener worked for the White Guard armies.

John Liers was Haskell’s closest associate and personal translator. Since the end of 1917, this man had been working at the American consulate in Russia, and a year later he became a consul. Back then, the Cheka recorded Liers’s connection with American Colonel Robertson, who was stationed in Vologda. According to the Cheka, Liers had transferred 18 million rubles to Robertson for subversive activities against the Bolsheviks. In 1922, Liers returned to Moscow as a senior official in the American Relief Administration.

The second category of employees was made up of Russian citizens, who were selected with great care.