Any discussion about the Russian government’s police and repressive policies toward its real and imagined political opponents must look at these policies in a broad context.

Simply describing the government structure in the Russian Empire as a police state does not give us the full picture of how the government faced challenges to its authority.

Furthermore, any study of government repression in Russia must be set within the wider European historical context. All European governments, starting especially with the French Revolution, faced challenges to their authority and developed police systems, formulated concepts of political crimes or crimes against the state, repressive policies against real or imagined political opponents.

But any comparative analysis of Russia and European countries leads us to the conclusion that somehow government in Russia was different from governments throughout Europe. Autocracy—the system of government in the Russian Empire—was what made the government structure of Russia so different from European countries.

Autocracy [самодержавие] can mean a system of government by one person with absolute power. This one person was the tsar or emperor. Autocracy seems similar to absolutism in Europe. Absolutism is used to describe how kings centralized their power through a bureaucracy and reduced the power of the nobility and the Church to compete with the rulers for power.

However, absolutism in European countries never totally concentrated power in the hands of the kings. Even in France, before the revolution, kings still faced huge challenges to their authority from the nobility, Church, court system, army, bureaucracy, elected assemblies, provinces, cities, and other corporative institutions and were forced to make concessions to them.

Historians often call these groupings intermediary bodies because they existed between the monarch and the general population and could serve as points of opposition to monarchs.

Government centralization in European countries only became possible after the revolutions between 1789-1849, the wars of unification in Germany and Italy. Centralization made it possible for governments to rely less on intermediary bodies and rely more on the bureaucracy.

Constitutions made it possible to specify the lines of authority between governments, parliaments, and court systems. Centralization also made it possible for governments to improve policing, formulate concepts of political crime, and to take measures against real or imagined opponents.

By the early 20th century, all European governments were either constitutional or semi-constitutional monarchies and republics.

Autocracy was what made Russia different from European countries. Of course, the government became a semi-autocratic/semi-constitutional government after the October Manifesto granted political freedom and a State Duma or parliament. However, the Basic Laws of 1906 still gave the government extensive powers and made it clear that power would not be shared with the Duma.

What made the autocracy so different was that it did not have to face competition for power from other bodies such as the nobility, Russian Orthodox Church, the army, and bureaucracy. The only competitor for power that the autocracy faced was from educated society largely beginning after the emancipation of the serfs in 1861.

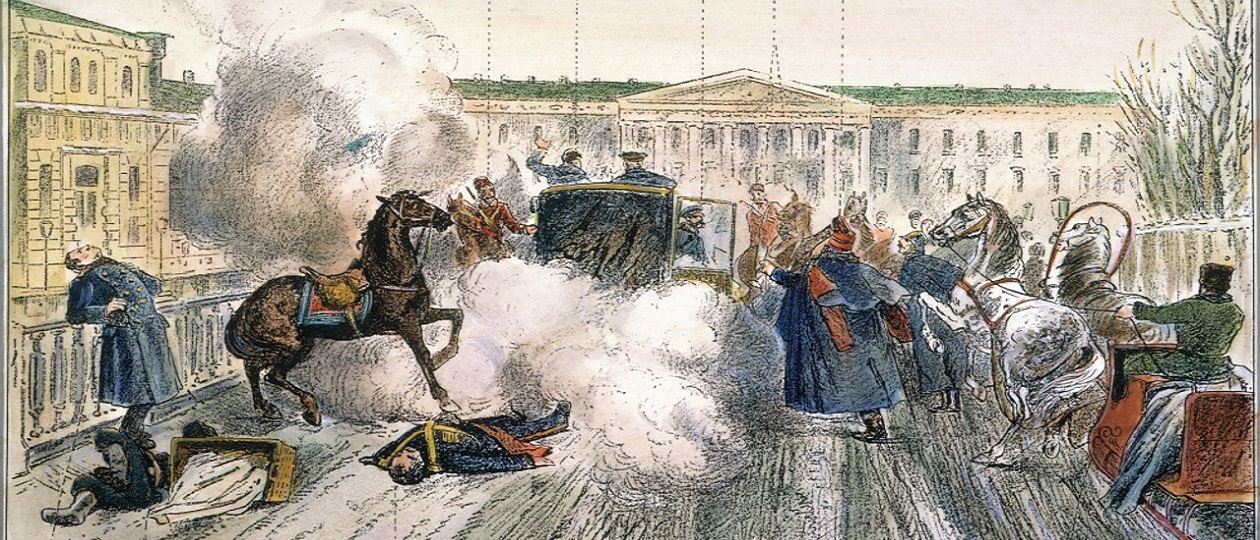

The People’s Will [Народная Воля]—the organization that assassinated Tsar Alexander on March 1, 1881—based its reasons for regicide—killing the tsar [цареубийство] on its understanding of the nature of the Russian state and society.

The Narodovol’tsy [members of the People’s Will] saw the main difference between Russia and Europe in the roles of state and society. In European countries, society had created the state, but in Russia the state had created society. The bureaucracy, army, Russian Orthodox Church, nobility, and bourgeoisie had been created by the autocracy and received their privileges from the state. These bodies were completely incapable of acting independently and of resisting the state. In Europe, these social institutions could compete with monarchs for a share of the power and the Narodovol’tsy believed the institutions had created European states.

The People’s Will was convinced that the concentration of power in the hands of the tsar was the Achille’s heel (weak point) of the Russian state. Assassination of the tsar would result in a quick collapse of the state.

Thus, assassination of the tsar was the main focus of Narodovol’tsy terrorism—striking at the centre. In their view, the state was the main exploiter and oppressor of the people. Reform of this regime was simply impossible. Overthrow of the autocracy and establishment of a representative government would speed up the possibility of a socialist revolution.

As noted in a previous article, Russian tsars, in distinction from European rulers, did not have a proper understanding about the state as a distinct organism, separate from their persons. The Russian language has similar words for state [государство, state] and ruler [государь, gosudar’]. Few tsars could understand the distinction. Emperors considered the state their private domain or fiefdom.

The People’s Will correctly understood the essence of the Russian state. However, in the conditions of their time, they could not foresee other ways of removing the tsar and overthrowing the autocracy. The abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in the February Revolution, and not an assassination, led to collapse of the Russian state and society within eight months. Nevertheless, the Narodovol’tsy correctly understood that the concentration of power in the hands of the tsar was the Achilles heel of the autocratic form of government.

However, the government could also be a force for reforms as the reign of Tsar Alexander II demonstrated. The reforms included the emancipation of the serfs, reforms in local self-government, the court system, censorship, universities, and the armed forces. Of course, in the reign of Alexander II, certain members of the government tried to restrict the reform. Tsar Alexander III has generally been accused of carrying out counter-reforms, but the Great Reforms simply could not be abolished. Tsar Nicholas II had a more hostile attitude toward reforms especially since he believed that he had signed the October Manifesto under duress and thought that he could restrict or abolish the Basic Laws.

All aspects of government policies were tightly connected with the big question of the political development of the Russian Empire. For the government and educated society, as represented by the political movements, the two main questions about Russia’s political development were:

- Would Russia become a European state? As noted, all European states in the period after 1861 were constitutional or semi-constitutional monarchies or republics.

- Would Russia go by a special path and remain uniquely Russian?

Responses varied to these questions. Reactionaries and conservatives were not the only ones believing in the specialness of Russia. Most socialists and many liberals thought the same way about Russia being unique.

There were those people in the government who believed that Russia could become a European state based on the rule of law. Even it did not have a parliament, rule of law was still possible. Other people in the government believed in the distinctiveness of Russia and saw severe policies as necessary because they believed that the Russian state was under permanent siege by its own population.

The main antagonistic forces in the Russian Empire from 1861-1917 were the autocracy and educated society. Terrorism was only one expression of this hostile relationship. How the government responded to challenges to its authority is the subject of the next article.

The relationship between government and society was shaped by the state structure that made Russia so distinct from European countries.

Citations

- Рокки Тони. Идеологическое и тактическое оружие организации «Народной воли»: как народовольцы стали легендарными в истории терроризма. (The ideological and tactical weapons of the People’s Will organization: how members of the People’s Will became legendary in the history of terrorism) // Сборник материалов VIII Международной научно-практической конференции. 7–9 октября 2020 г. Тула-2021, с. 421-432.

- Рокки, Тони. Европейская «Эпоха динамита» и политический терроризм в Российской империи: уроки истории (The European <<Era of Dynamite>> and political terrorism in the Russian Empire: lessons of history.) // Сборник материалов VII Международной научно-практической конференции. 16–18 октября 2019 г. Тула–2020, с. 412-421