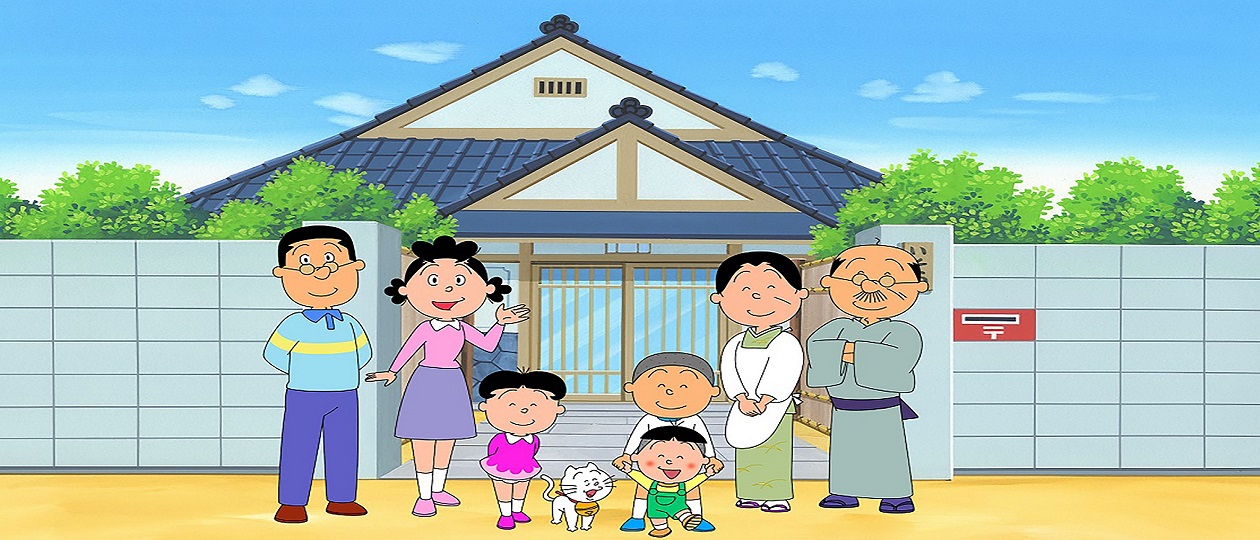

There is one anime that you can be sure every single person in Japan knows, young and old alike, and that everyone has seen at least one episode. It’s inescapable but still largely unknown outside Japan. It is called Sazae-san.

Although not many Western fans of anime and manga know about Sazae-san, but you should. The series follows a young woman named Sazae-san, her family, and the comical hijinks of daily life as they cope with the aftermath of World War II. The four-panel comic hit newsstands in 1946 and ran every day until 1974. The collected volumes have sold over 62 million copies and the anime—which began in 1969—is still on air.

For foreigners Sazae-san seems old-fashioned, depicting a world before mobile phones and the internet. For Japanese people, it depicts an idealized extended family living together. Families get together and watch the show each Sunday, so its appeal is probably wider any weekly TV anime. The show is part of the regular rhythm of Japanese life in a way few things are.

At the end of the show, Sazae-san plays paper-rock-scissors with the viewing audience, and people across the country play along with their TV screens, throwing out rock, paper, or scissors. Part of the fun is seeing who can beat Sazae. That means every Sunday millions of Japanese people are playing paper-rock-scissors at the exact same time.

While Sazae-san might seem like it’s from a bygone era, when the original manga debuted in 1946, it was cutting edge. Sazae-san’s creator, Machiko Hasegawa, was very much a modern and opinionated woman and so was her heroine Sazae-san.

Machiko Hasegawa was born in 1920 in Kyushu and grew up there with her parents, her older sister, and her younger sister. After her father died when she was fourteen, her family moved to Tokyo, where she graduated from an all-girls high school. She began drawing cartoons as a teenager and, at sixteen, began an apprenticeship under the famous manga artist Suiho Tagawa. At eighteen, her first cartoon, Badger Mask (Tanuki no Omen) was published in 1938 in the magazine Shojo Club (少女クラブ).

In 1944, during World War II, Hasegawa and her family were evacuated to Fukuoka prefecture in Kyushu. It was there, living by the seaside, that Hasegawa came up with Sazae-san and her colorful marine life-inspired family (“sazae” 栄螺is also the word for shellfish). She jotted ideas down in her notebook while she worked in her vegetable garden; her younger sister helped, functioning as a sounding board for her ideas.

Sazae-san was first published in a local newspaper in April 1946. By the end of the same year, Hasegawa and her family had moved back to Tokyo. At her older sister’s insistence, Hasegawa set up a company with her sisters that immediately began publishing collected volumes of Sazae-san. In December of 1949, the evening edition of the Asahi Shimbun began publishing the series, making her Japan’s first successful female manga artist.

In the original manga, Sazae was a feminist, didn’t think the man was the head of the household and joined the women’s liberation movement.

Overall, though, Sazae-san’s family is loving and supportive. They get into fights as family members do and play silly pranks on each other. The comics don’t just follow Sazae-san, but also depict a variety of situations and perspectives: kids, parents, dads, moms, wives, husbands, and the elderly. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the majority of Sazae-san comics don’t overtly address gender roles or expectations. Clocking in at a total of 6,477 strips, there are many other mundane and daily topics to be considered—such as poop jokes.

While most Sazae-san strips focus on the humor of daily life, it’s very much cognizant of the changing expectations and gender roles for women and men that happened after World War II. In 1945, after decades of activism, Japanese women finally earned the right to vote, and women’s rights were clearly on Hasegawa’s mind.

In one strip, a young man serves an older woman tea—typically a role a young woman would perform. The older woman chides the young man for such “scandalous” behavior. An older man sees this interaction and bops the older woman on the head with his cane and calls her behavior “undemocratic.” Sazae-san, not realizing what happened earlier, bops the older man on the head with her umbrella for mistreating the older woman. She exclaims: “What about equal rights?”

In one comic, Sazae-san’s father and husband jokingly claim that “women are behind men.” Sazae-san and her mom disagree and point out the men’s claim is just “male chauvinism.” The last panel shows the family eating a bare-bones dinner without Sazae-san and her mom, while Katsuo complains that the men should have had this argument after Sazae-san and their mom prepared dinner. It’s a light touch, granted, but it still doesn’t let the men get away with sexist behavior.

While Sazae-san is seen as progressive for its time, I think it’s important to note that it sometimes falls short of present-day feminist ideals. For one, the feisty Sazae-san does not work outside the home. She functions as an endearing but imperfect caretaker for her parents, younger brother, and sister, as well her husband and son. As such, sexism in the workplace is explored through the men in Sazae-san’s life like her husband and father, but not through an actual woman’s viewpoint. There are also quite a few comics whose jokes rely on characters being ugly—all of whom are drawn with large lips, freckles, and pig noses.

The manga was left-leaning for its time, but now in 2020, the anime feels apolitical and doesn’t really address contemporary Japanese societal issues, which is why it might feel dated for modern viewers.

Regardless, it’s still funny and there is another reason why you should watch it.If you are learning Japanese, this is the anime to watch. The vocabulary is stuff you’ll come across on a daily basis, which some anime which are filled with words that won’t get regular use, and the characters speak at a natural cadence. It’s a practical and useful study aid.

Also, it’s an excellent way to see how different members of the family talk to each other as well as how they talk to their friends and colleagues. When speaking Japanese, there are different levels of politeness, and Sazae-san provides excellent examples of how to correctly use formal and informal language.

Best of all, each episode centers around a Japanese cultural idea or norm (sometimes even an idiom) or a seasonal motif. That way, as you watch, you can learn useful and applicable things about Japan and Japanese culture, unlike some anime which paint a far more abstract view of the country.