Nikolai Miklouho-Maclay Jr. brought the skulls of the inhabitants of Papua New Guinea to their historical homeland.

The remains of several dozen people were taken to Australia and Russia for research in the 19th century by the famous Russian scientist Miklouho-Maclay Sr. On February 19, the skulls will be handed over to the descendants of the inhabitants of the Rai Coast a.k.a Maclay Coast for burial, the Miklouho-Maclay Foundation reported.

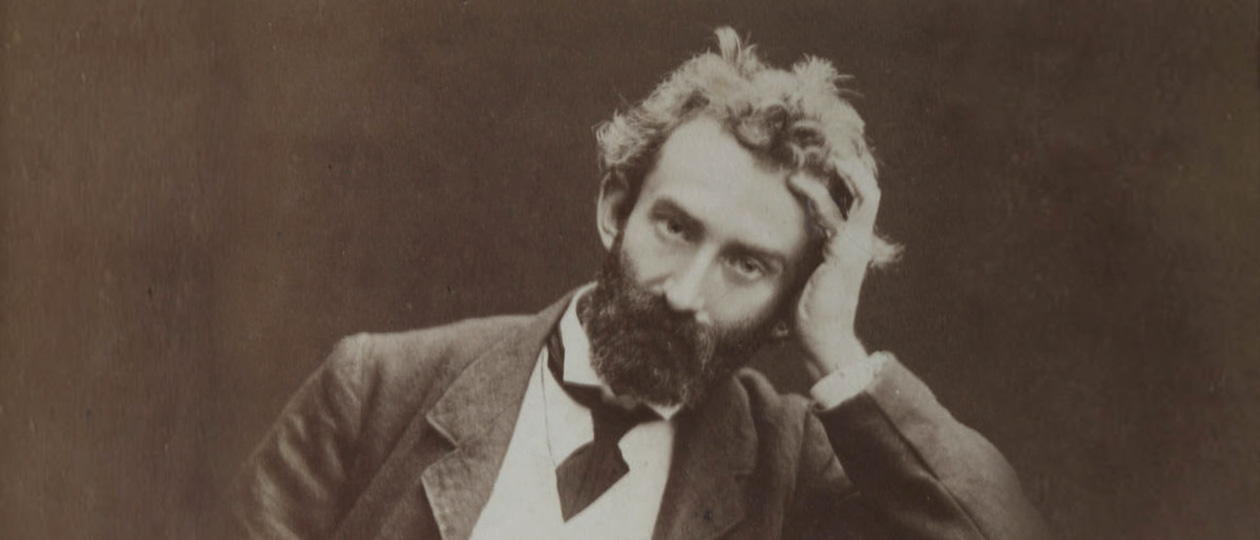

This story began about 150 years ago, when Miklouho-Maclay collected skulls without lower jaws in New Guinea.

Locals tied them to the roofs of huts to preserve the memory of their deceased ancestors. The remains were of no particular value, so the islanders handed them over to the Russian scientist for research.

Some of the skulls brought back from Miklouho-Maclay’s expeditions became part of the collection of the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera) in St. Petersburg.

Others ended up in Australia and were later exhibited at the Chau Chak Wing Museum at the University of Sydney.

Research based on the collection, conducted by the scientist in the 19th century, helped to obtain evidence against racist theories that dark-skinned people are at a lower stage of development and cannot be considered Homo sapiens, like Europeans.

In 2022, the traveler’s descendant and namesake, the founder of the Miklouho-Maclay Foundation for the Preservation of Ethnocultural Heritage and the head of the Center for the Study of the South Pacific Region of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Nikolai Miklouho-Maclay Jr. visited Sydney.

In the university museum, he was shown 16 skulls — part of the same collection that was collected in the 19th century.

Some of the skulls had names: Andan, Ibor, Kake, Panake — these were people who lived in the territory that is today called the Maclay Coast.

Their places of residence were also indicated. All this was supported by the personal notes of the Russian scientist.

Miklouho-Maclay Jr. initiated and organized the process of restitution of the skull collection. He went on an expedition to Papua New Guinea to study the impact of globalization and the emerging high-speed Internet on the lives and traditions of the indigenous people of the Maclay Coast.

The scientist visited ten villages in Astrolabe Bay and met with the elders of many clans. He told the indigenous people why the skulls were collected a century and a half ago and what results it led to.

In the villages on the Maclay Coast, Miklouho-Maclay Jr. conducted about 20 interviews and learned that the locals knew nothing about the remains of their ancestors.

They all expressed a desire to return the skulls to their homeland for burial. The scientists provided interviews and letters from the islanders to the Chau Chak Wing Museum. After that, the official restitution process was launched.

The skulls stored in Australia were first delivered in special containers to Port Moresby and then to Madang.

A ceremonial event will be held on the Maclay Coast, near the N.N. Miklouho-Maclay memorial on Cape Garagassi, to mark the return of the ancestors’ skulls to their native land. They are also planned to be buried there.

In honor of this event, the residents of the Maclay Coast villages will hold an “Ai” festival with traditional sing-sing dances.

The Miklouho-Maclay family faced a similar situation. The skull of the famous 19th-century scientist and traveler is now stored in the Kunstkamera “for the benefit of science and humanity,” as he himself bequeathed.

The museum reconstructed Miklouho-Maclay’s face, partially hidden by a beard during his lifetime, and found out that he died of jaw cancer, and not from tropical diseases, as was previously assumed.

The researcher’s relatives believe that his skull has already served science and humanity well, and it is time to bury it.