Jack London Covered The War Where My Ancestors Fought: Part 1 and Part 2.

In Chemulpo Jack London found out that the war he was supposed to cover had begun a week before and that on its very first day after a brief battle with a Japanese squadron, Russian sailors instead of surrending sank their Varyag and Korietz battle ships, plus the merchant ship Sungari. Still, London felt it necessary to inspect the site of the naval battle.

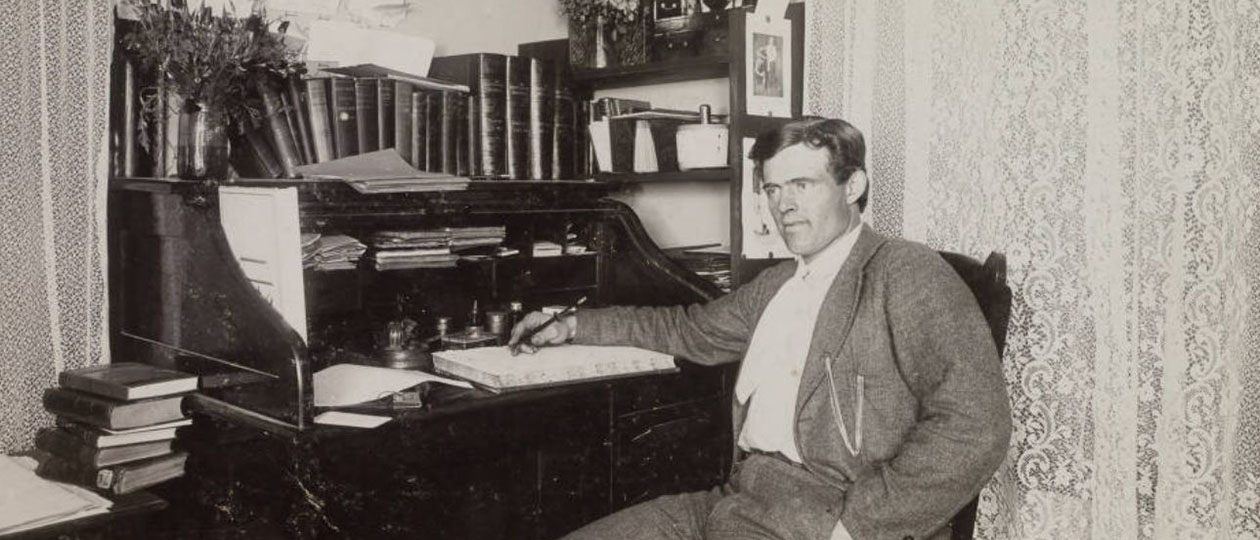

“I was greeted by the masts and pipes of the ships sunken in the Chemulpo harbor,” he noted in his diary. On March 4th , London reached Pyongyang. “I covered 180 miles on horseback,” he wrote to Charmian Kittredge.” I’ve got one of the best horses in Korea. It used to belong to Russia’s ambassador in Seoul before he left.” He meant Alexander Ivanovich Pavlov and his mare Belle.

On February 12th , Pavlov had left Seoul. Before his departure in an interview with a British journalist, he either bluffed, or actually shared what the majority of Russian officials thought: “There will be no war. But if it happens, the Japanese will lose their fleet and will plead for peace.” On the same day of March 4th , Jack London sent a remarkable report to The San Francisco Examiner: “I don’t know if there are any other soldiers in the world as disciplined as the Japanese. The Americans would have turned Seoul upside down with their antics and merry debauchery, but the Japanese are deadly serious. The Japanese are a nation of warriors. Their infantry is beyond praise.”

London also noted that the Japanese army had the best types of modern equipment: “The Japanese use all the achievements of the West.” In his assessment of the Japanese army, the American war correspondent demonstrated much greater sobriety and insight than Russian military experts. Typically, Major General Yakov Grigorievich Zhilinsky, chief military intelligence officer of the Russian army, believed that “The Japanese army cannot be compared with European armies, and especially with ours.”

Meanwhile the Japanese authorities did not allow foreign war correspondents to approach the sites of clashes with the Russian army. Only on May 1st London managed to eyewitness the battle on the Yalu River. There the Japanese inflicted heavy lossed to their adversary: “400 Russians and 28 cannons were captured.” According to retired US Army Colonel John Mancini, “London was the first to send photographs from that war to the United States.” Three weeks later, Jack London sent another letter from Manchuria to his fiancée: “I am so sick of being here! Never before war correspondents had been treated the way we are treated here.”

On May 14th , London drafted a joint statement by foreign correspondents accredited to the Japanese army in Manchuria and outraged by the harsh censorship. Under the circumstances, London even wanted to ask to be transferred to the Russian army. Before it could happen, though, he was forced to return to the United States. “London’s pugnacious nature got him into an international scandal,” said John Mancini’s article in Military History magazine. “He hit a Japanese man who was stealing fodder for his horse. As a result, he was arrested by the Japanese military for the third time in four months. This time, however, he faced a court martial and a possibility of death penalty”.

The situation was so serious that required Theodore Roosevelt’s intervention. The US President was a great fan of Jack London’s Northern Tales and asked the Japanese authorities to release his compatriot. Which they did, demanding that The San Francisco Examiner war correspondent should leave as soon as possible. Thus, London spent less than half a year at the Russo-Japanese War, and did not even really see it (which was not his fault at all). Nevertheless, according to John Mancini, Jack London still managed to publish more reports than any other Western war correspondent.

American orientalist Daniel A. Métraux agreed: “Many other famous journalists covered that war, but only London was able to provide first-class frontline reports. The rest of the reporters hanged around Tokyo, because they lacked London’s courage to get from Japan to Korea.” Besides, according to D. Métraux, Jack London proved to be an outstanding prophet as he recognized the enormous potential of Japan and China and predicted their rapid growth in the 20th century. He even forecasted that China would become a superpower by mid-70s. Also, as Daniel A. Métraux emphasized, London “was ahead of his time in terms of intellectual and moral senses. His reporting of the Russo-Japanese War was balanced, objective and demonstrated concern for the well-being of both Japanese and Russian soldiers, as well as Korean peasants and ordinary Chinese.”

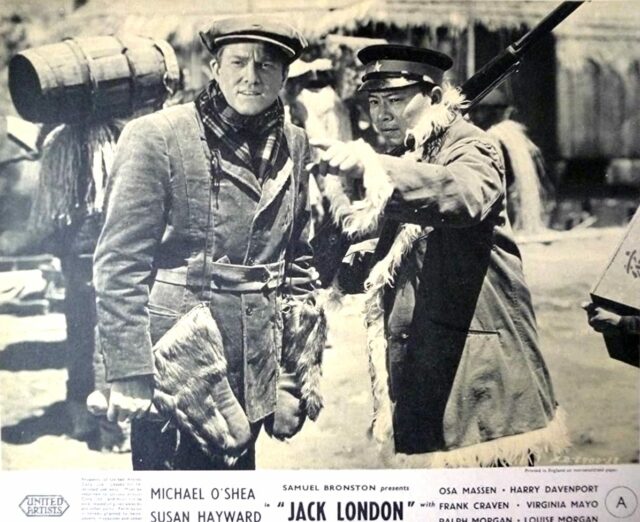

Shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hollywood filmed a biopic, Jack London, based on a script by Charmian Kittredge. It was billed as “true adventures of a tough American hero.” The movie emphasized London’s involvement in the Russo-Japanese War, and the poster was designed accordingly. In it, Jack London looked like a prisoner, and the inscription said: “First American prisoner of the Japs”. London did not manage to see it as he had died a quarter of a century before, at almost the same age as my great-grandfather Afanasy Ilarionovich Reshetnikov who was killed in Manchuria.

John Mancini believes that Jack London’s early death was connected with that war, too: “He died when he was only 40 due to numerous health problems. They resulted from his life style at the limit of his capabilities. This is how he lived in 1904 in Korea, too.”