Back in April 1982 US media revealed President Reagan’s intention to have lunch with a group of Soviet dissidents who had emigrated to the West. Their list contained the names of about a dozen of persons barely known to American people.

Meanwhile, the extraordinary event was planned to coincide with the renewal of the Soviet-American nuclear disarmament talks, long delayed by Washington. It demonstrated the armament double track policy towards the USSR taken by the Reagan administration. The Soviet American dialogue slowly trudged down the single line track with its frequent lengthy stops, and, by the second track, the locomotive of confrontation was speeding up in full force with a desperate whistle and ominous firebrand clouds.

In Washington the discussions on the subject of localized nuclear conflicts became louder and more common. US Secretary of State Alexander Haig said, there are things more important than peace, and the main Kremlin-ologist of the White House Richard Pipes factually stated an ultimatum: Kremlin either denounces Communist ideology, or it faces WWIII. So, the banquet for dissidents was invented as an important propagandist-political act. The only thing missing was a person capable to give this enterprise the necessary glamour and resonance.

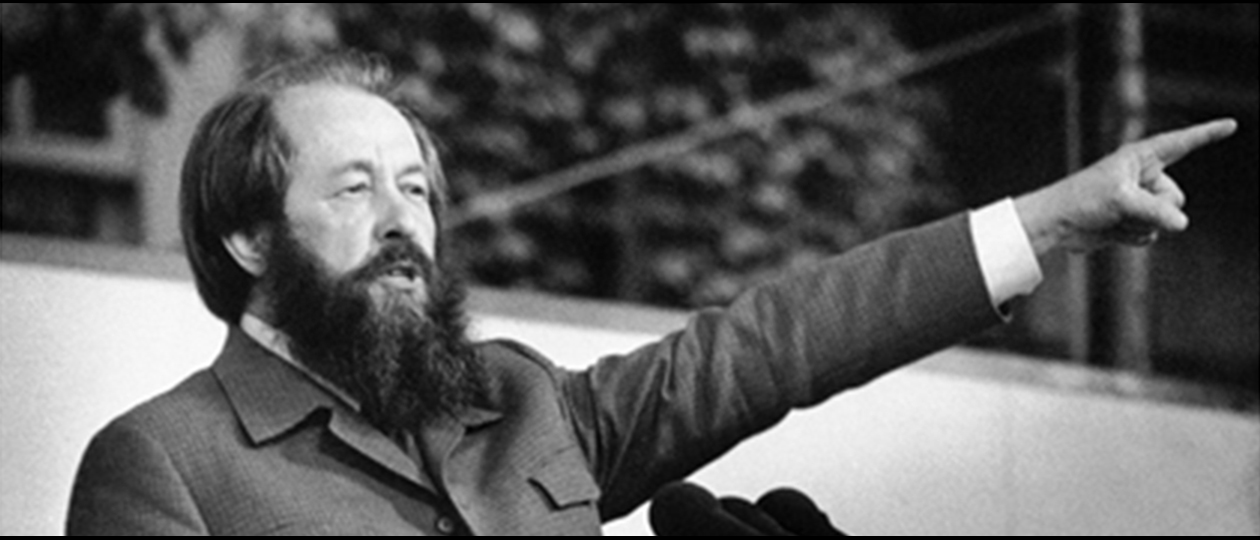

And then the news came in: Alexander Solzhenitsyn will attend a banquet with Reagan. The curiosity in the promised event has immediately soared: other invitees were no match to Solzhenitsyn, Americans had no need for an explanation of who and what he was. It would be an exaggeration to say that he was a master of thought in the USA (there, they have a different approach to literature than in Russia).

Nevertheless, some places introduced “the Gulag Archipelago” to the lists of the extracurricular literature for the local students. And this is considering the overwhelming majority of other contemporary Russian authors were alien to the Americans, and the Americans had no desire to know them, which has been proved to me by TV and Radio debates with local officials, politicians and journalists.

The promised visit of Solzhenitsyn to Washington was presented in a similar way to how the American television advertises its “soap operas”: will the Russian hermit break his multiyear self-imposed imprisonment? Is he ready to renounce the heresy that caused him to be excommunicated from the American society? Will he come to peace with the local way of life and thinking? The public’s curiosity was further teased by the gossips of the White House’s indecision: to invite Solzhenitsyn or not?

Here I have to explain something, coming from the things I’ve seen and read myself (prior to my assignment to the United Stated, I lived and worked in Canada for five and a half years, so practically the entire overseas life of Solzhenitsyn – the public part of it, of course, – went on in front of my eyes).

Upon arriving to the USA, Solzhenitsyn settled in a middle of nowhere – in Cavendish, a tiny town that can only be spotted in the most detailed maps of the equally tiny state of Vermont. This region is famous for its untouched nature and is known for being the original home of Yankees, but Solzhenytsin, it seems, liked it for how it resembled the Russian North and its remote location distant from the noisy and rushing way of the American life.

In his quest for total solitude, the writer has barred himself even from the small number – less than fifteen hundred – of the Cavendish residents, and he did so by buying 5 acres of land with an unusual for Americans fencing, a house and a three store buildings, which, in addition to working spaces, included a church and a classroom for the studies with his children – and he didn’t leave it ever since.

The neighbours of Solzhenytsin were seriously offended. In the USA it is a custom to actively communicate with each other within the borders of your “community”, and here they’ve got a global celebrity visiting their town – only to completely avoid the locals. When the wave of dissatisfaction reached the estate of Solzhenytsin, its master send his wife to attend the Sunday service in the local church – to give an explanation to the people. There, she thanked the residents of Cavendish for their hospitality and asked for their understanding in dealing with the behavior of her husband, consumed by the literary work.

It was true, Solzenytsin worked as if he was cursed. The Americans, a hard working nation themselves, were satisfied with the explanation they’ve got. However, Kurt Vonnegut JR, in one of his interviews with an American newspaper on the lifestyle of his Russian “coworker”, expressed his distaste: “He is uninterested in his neighbors, it’s like he is still in the USSR”.

Can it be blamed solely on Solzhenytsin’s obsession with his work? I don’t think so. And now it is the right time to recall his 1978 speech in Harward university, and what followed after.

By that time, the fame of Solzhenitsyn in the USA has reached its peak. His visit to the most prestigious American university, where he was granted a honorary diploma, was planned triumphal. Thousands of people, despite the rain, came to the pine forest to look at the legendary person that challenged the system the Americans of that time regarded with a hostile suspicion. The speech of the celebration’s subject was supposed to be the apotheosis, it was awaited like the words of a prophet.

In a French-style jacket, with a beard unusual by an American standard, and with the spirituality of his appearance characteristic of the orthodox believers, Solzhenitsyn indeed resembled a prophet that day. When the praises in his name went down and he took the text of his speech out of his chest pocket, the crowd held its breath, looking at the idol with a touched excitement. Captured by the TV cameras, the shared expression of their faces remained on the screen for another ten minutes, while the speaker, via his female interpreter, praised those who supported him during the years of hardship.

But when Solzhenytsin moved to the heart of the matter, the cameras captured the unforgettable metamorphose: the faces of the attendees began to elongate, turn dark and stone-like. The quiet satisfaction with which they listened to the orator became a grim silence, the tv screens began to emit the chill of alientation. The end of the speech was greeted with weak applause.

A couple of days later, having recovered from the shock, the North American media changed its mercy to anger and burst out with responses, the gist of which boiled down to the fact that Solzhenitsyn turned out to be an ungrateful, obstinate person, not at all like the simple-minded and trusting Americans imagined him to be. But now, they say, it has become clear that he is a mossy conservative, a monarchist and almost a serf owner. After which there will be no word from him for many years. Why did Alexander Isayevich annoy the Americans so much? Because he neglected one of their peculiarities: an extremely painful perception of criticism addressed to him.

In the USA, pluralism of opinions even in those days did not have such wide boundaries as it seemed from the outside. Solzhenitsyn dared to go beyond them, launching into discussions about the advantages and disadvantages of Western democracy.

Noting that people in the East are poorer in material terms, but richer in spiritual terms than people in the West, he reproached the latter for pride: they are used to measuring everyone and everything by their own yardstick and consider their own society a model for universal imitation. Meanwhile, according to Solzhenitsyn, the law of balance of rights and obligations is violated in the Western model of democracy, for which it pays with a decline in morality.

So, this is what preceded Solzhenitsyn’s invitation to a reception at the White House four years later. That is why they were not particularly embarrassed to figure out what they would get from this meeting. And that is why this whole story caused such a resonance in the USA. The embarrassment was even greater when Alexander Isayevich did not show up for the presidential dinner.

Then the offended Reagan administration spread a rumor: supposedly, Solzhenitsyn did not want to sit at the same table with the other dissidents because of… his anti-Semitism. The White House knew how to manipulate the press. Solzhenitsyn, however, made a counter-move, through his wife, suggesting that the Washington Post publish the text of his letter to Reagan outlining the true reasons for refusing to accept the invitation to a dinner party.

The Washington Post did not need to be persuaded: it was in opposition to the head of the White House and immediately published this remarkable document under the headline “Solzhenitsyn replies to Reagan: “I humbly thank you.”” Alexander Isaevich provided his message to the US President with the stamp “personal, confidential,” which meant that it was not intended for outsiders until circumstances prompted the author to make it public.

Having expressed in his first sentence his admiration for many aspects of Reagan’s work and his joy for the Americans who had such a president, Solzhenitsyn then wrote: “But I never sought the privilege of being invited to the White House – neither under President Ford nor later.” As of late, Solzhenitsyn added, he got signals that such an invitation could be extended to him by Reagan’s administration. To which Alexander Isayevich responded that he was ready to have a substantive discussion with the President rather than a ceremonial meeting because, Solzhenitsyn stressed, he did not have spare time for any symbolic gestures.

Against this background Richard Pipes called Solzhenitsyn to say that he was invited to have lunch with Reagan on May 11th in a company of some other emigrees, branded as “Soviet dissidents” but not personified to Alexander Isayevich. Accompanied by the fact that all that was leaked to the press, where Solzhenitsyn was described as “a symbolic figure of Russian nationalism”, the writer felt offended and rejected the invitation to the White House on such terms.

Since then, Solzhenitsyn never fell on his knees before the powers that be in the US, as, for example, Mikhail Baryshnikov did – literally – at the gala concert in honor of Reagan’s re-election as president. Solzhenitsyn’s books continued to be published and republished, but due to their high cost and low print runs, they were available only to passionate lovers of fiction, and there are few of them overseas, by our standards.

This is the very situation that Charles Wick, then director of the US Information Agency, acknowledged in one of his television discussions with me, justifying the limited outlook of his compatriots: “In our country, there are no bans on publications, but what is published is sometimes circulated only in a narrow circle.”

In short, Solzhenitsyn lost his former “publicity” in the United States. Only six years later, on the occasion of his 70th birthday, Time magazine published an interview with him, repeating much of what was said in Solzhenitsyn’s letter to Reagan: the flow of false rumors and speculation does not dry up, they continue to stick labels – “obscurantist”, “monarchist”, “nationalist”.

In essence, Solzhenitsyn said this even earlier, speaking at Harvard University: “Without any censorship in the West, a meticulous selection of fashionable thoughts from unfashionable thoughts is carried out – and the latter, although not banned by anyone, have no real path either in the periodical press, or through books, or from university departments.”

2 comments

Kristina Zimmer

02.11.2024 at 08:57

Wow amazing site layout. How long have you been running this site? The overall look of your website is magnificent as well as the content.

Anonimus Zero

02.11.2024 at 18:45

Thank you for the detailed write-up! It was such an enjoyable read. I’d love to stay connected—how can we communicate further?