10 days before the US presidential election, Izvestia’s film crew sent from Moscow to cover the event was detained at the Washington airport.

The Russian reporters had valid entry visas, but their equipment was taken away, and they were interrogated for several hours. Cameraman’s visa was cancelled and he had to return to Moscow. Which resembles an incident with another Izvestia journalist, Washington-based correspondent Melor Sturua who was stripped of his accreditation by US authorities 42 years ago.

In August 1982, Andrew Nagorski, Newsweek’s Moscow bureau chief, was declared persona non grata by Soviet authorities “for impermissible journalistic activities.” In diplomatic language that often stands for espionage.

Nagorski arrived in Moscow in May 1981. This is how he described his stay in the USSR 32 years later:

«I quickly — and often — irritated the Kremlin. Solidarity was on the rise in Poland [it’s noteworthy that Nagorski was Polish by origin — A.P.]. I visited neighboring Lithuania to report on whether that Western outpost of the Soviet Union was vulnerable to similar discontent. I met with the remnants of the dissident community, survivors of successive waves of crackdowns. I hunted out independent writers and “refuseniks,” Jews who were repeatedly denied permission to emigrate and stripped of their jobs in the process.»

Many Western journalists stationed in the USSR were doing just that, but Nagorski «played cat and mouse games with the KGB to protect those Russians brave enough to supply me with information while still trying to cling to their official positions. That meant going to great lengths, literally. I never called them from my tapped office or home phones. Instead, I’d walk a long way from our foreigners’ housing compound to make a brief call after dropping one of the 2-kopeck coins I always carried into a pay phone. We’d exchange a few words, never mentioning my name. We’d signal a time and place to meet, usually using a code we’d worked out beforehand.»

Less than a year after starting his assignment in the USSR, Nagorski managed to find out that Leonid Brezhnev’s health had deteriorated so badly that he was only alive because of the extraordinary efforts of his medical team. On April 12, 1982, Newsweek ran a cover story “Brezhnev’s Final Days” with a crumbling bust of Brezhnev and smaller lines below saying “The Succession Struggle” and “Communism in Crisis.”

Just imagine what it was like for Leonid Ilyich and his family to see this 7 months before his actual death. No wonder that Nagorski was expelled. But why it took Soviet authorities 4 months after the scandalous issue of Newsweek was published? In a detailed recount of his 15-month stay in our country, Nagorski provided no clue. Could there be some other reason for his expulsion from the USSR?

Anyway, as soon as Nagorski was declared persona non grata, our embassy in Washington received a relevant coded cable from the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Next day, the embassy got a call from the US Department of State summoning the head of our press office.

It was August, and many Soviet employees in the American capital had gone on vacation. They included our ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin, who was substitued by chargé d’affaires Alexander Alexandrovich Bessmertnykh, and press department’s chief Valentin Kamenev. For that reason his deputy, Boris Davydov, had to answer State Department’s call.

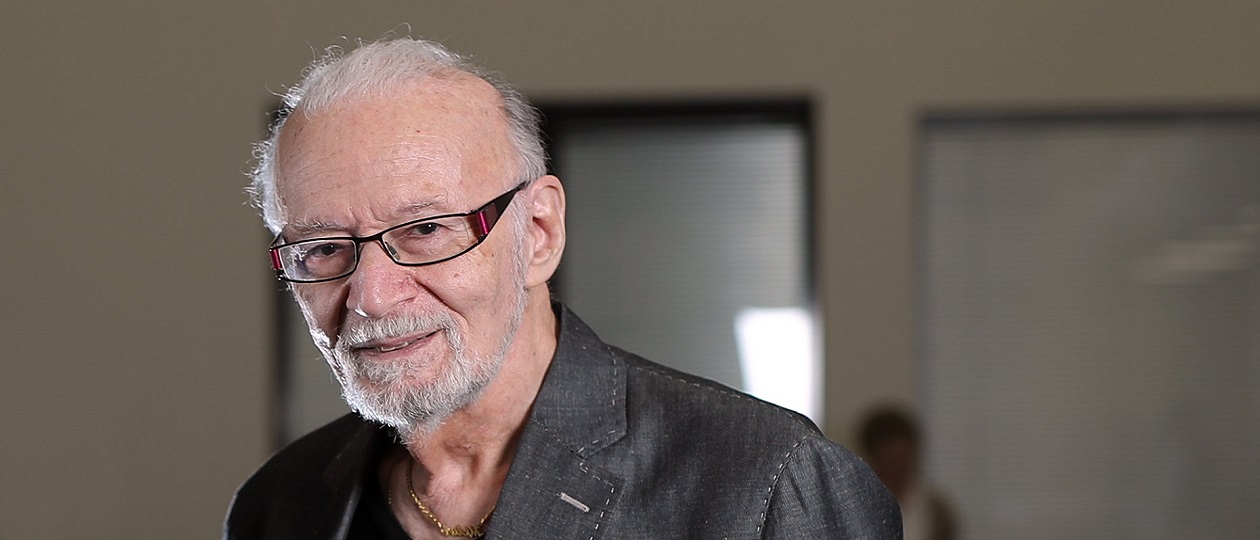

I happened to visit the Soviet embassy when Boris returned from the Foggy Bottom (nickname for the US Department of State). “Come with me to Bessmertnykh” — he suggested. — “We need to discuss a problem with your colleague Melor.” (Izvestia’s Washington bureau chief Melor Sturua was on a vacation, too. At that very moment, together with his wife Edda Mikhailovna, he enjoyed a transatlantic voyage aboard “Gruziya” ocean liner).

In Bessmertnykh’s office, Davydov reported on his visit to the State Department: «As usual, they expressed indignation about the expulsion of Nagorski. They called it unfair and demanded that this decision should be recalled. This was followed, though, by something unprecedented, something I’ve never heard before. [Similar to Bessmertnykh, Davydov was on his third long-term assignment in the USA — A.P.]. I was told, verbatim, the following: “Unless the Soviet side reconsiders its decision to declare Andrew Nagorski persona non grata, the US authorities will be forced to take retaliatory measures by revoking the accreditation of Melor Sturua, Izvestia’s bureau chief in Washington.»

«This is unprecedented,” Davydov said once again. “Previously, on such occasions, the Americans would say right away: in retaliation for the expulsion of our official representative in the USSR, we are expelling such-and-such Soviet employee. Instead they used an evasive phrase in subjunctive mood, plus they gave us a week for consideration, while Nagorski is packing his bags in Moscow.»

Bessmertnykh reacted immediately: “This is the most convincing proof of Nagorski’s importance to American authorities! That’s why out of three dozen Soviet reporters in Washington, New York and San Francisco they chose Melor as the bargaining chip. They know that he’s got influential patrons in Moscow who may interfere on his behalf.”

«Boris, — Bessmertnykh continued, — draft an urgent coded cable to our Foreign Ministry with a detailed report of your visit to the State Department. And I will add, “In our opinion, we should not give in to the American blackmail. We propose to reject their demands and to leave the decision to expel Andrew Nagorski in force.»

As a result, while MS “Gruziya” with the Sturua couple was still on its way to Odessa, Newsweek’s former Moscow bureau chief was taking up a new assignment in Rome.

The Americans’ idea of exchanging Sturua for Nagorski, was apparently due to the fact that 10 years before Edda Mikhailovna had married their eldest son Andrei off to Mikhail Andreyevich Suslov’s granddaughter Elena. As a result, she managed to solve several family problems in one stroke. Since then, Melor Georgievich, whose own father used to head the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic, would use any pretext to mention his relationship with Suslov, chief Soviet ideologist who made even Brezhnev trepidate.

Suslov passed away 6 months before, but Sturua had other influential patrons in Moscow. He claimed that he combined his work at Izvestia with the position of Khrushchev’s speechwriter, and later ended up in Brezhnev’s inner circle. In early 70s, being a great lover of rare cars, Leonid Ilyich offered Melor Georgievich any amount for the Dodge Charger that Sturua had brought from New York.

To be continued…

Melor Sturua As a Mirror of Soviet Elite’s Evolution: Part II