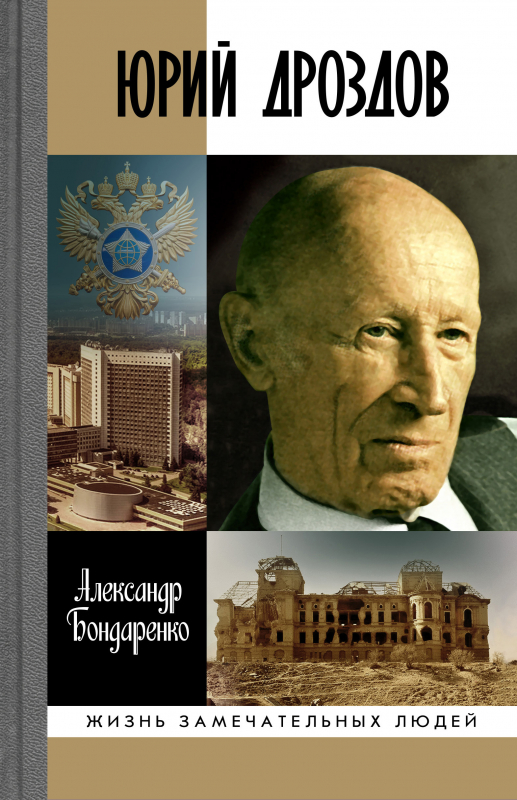

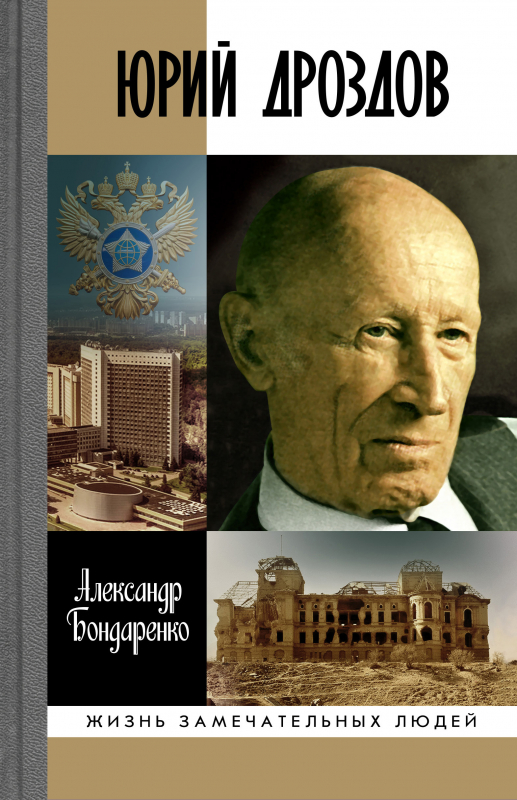

September 19 marked the 100th anniversary of the birth of Yuri Ivanovich Drozdov, whose name is associated with an entire era in the history of the KGB’s underground intelligence service. It was under his leadership that the Vympel special forces group was created, and the first Heroes of the Soviet Union emerged among the KGB’s underground agents.

The future “legal illegal” was born on September 19, 1925, in Minsk. His father, Ivan Dmitrievich Drozdov, was an officer in the Russian army who fought in World War I and was awarded the St. George Cross for bravery. After the revolution, he served in the Red Army, serving as an artillery commander in Chapayev’s division. He was at the front from the first days of the Great Patriotic War and was seriously wounded near Staraya Russa.

His son followed in his father’s footsteps. After graduating from the 1st Leningrad Artillery School in 1944, which was evacuated to Engels, he stormed Berlin at the age of 19 and was awarded the Order of the Red Star “for the destruction of two 75-mm cannons, one anti-aircraft gun, 5 machine guns with crews, and up to 80 enemy soldiers.” He celebrated Victory Day with the rank of lieutenant and continued his service in Germany.

In 1952, Yuri Drozdov entered the Military Institute of Foreign Languages, Faculty 4 (decomposition of enemy troops and populations), where he mastered German and English. In 1956, he was assigned to work in the Office of the KGB Representative for Coordination and Liaison with the GDR Ministry of State Security, Department “N” (illegal intelligence).

The KGB representative in Berlin at the time was the notorious “king of illegals,” Major General Alexander Mikhailovich Korotkov, and the head of Department “N” was Colonel Nikolai Mikhailovich Gorshkov, who recruited Georges Pac, who became deputy head of the NATO press service.

To begin operational work alongside such aces, the former artillery captain had to answer just one question: could he “shape” another person’s life? To overcome his own limitations, Drozdov had to spend hours wandering around West Berlin, listening to German speech, imitating their mannerisms, and even attending drama school.

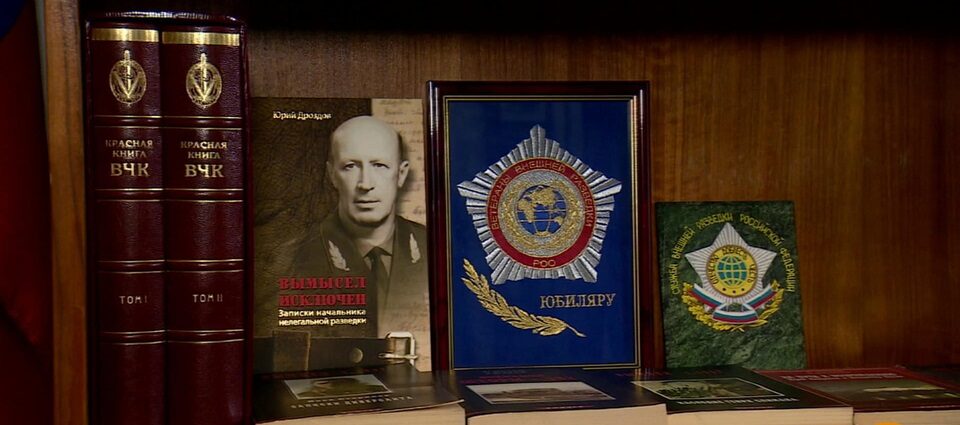

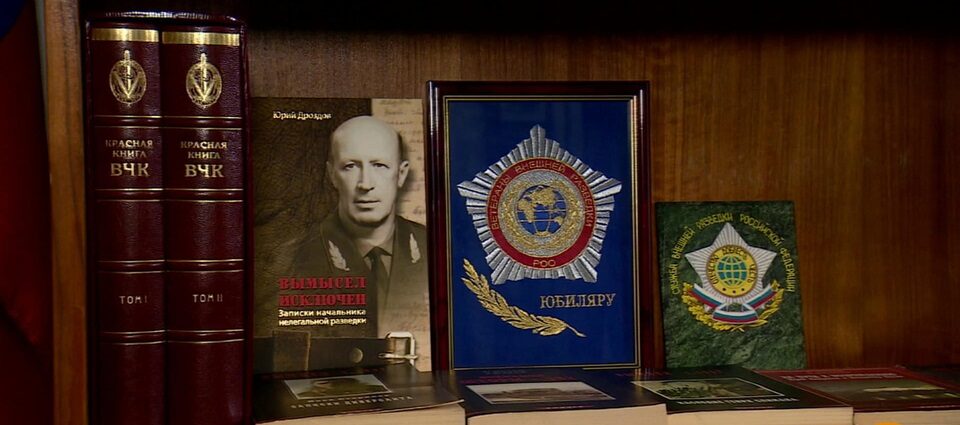

In the spring of 1958, Drozdov was summoned by his department head, Gorshkov, who placed a copy of Der Spiegel magazine with an article entitled “The Emil Goldfuss Case” on his desk and asked him to consider a plan to free William Fischer, a Soviet illegal immigrant who had identified himself as Rudolf Abel, who had been arrested in New York in June 1957.

To begin with, it was decided to establish correspondence between Abel’s “family” and his lawyer in the United States. To this end, the Center created a cover story about Abel’s “cousin,” Jürgen Drivs, who was living in the GDR. Drozdov was to carry out this mission. “I was creating a very ordinary cover story—that of a simple office worker,” he recalls. “I was walking down the street and noticed a building, half-ruined… On the iron bars surrounding the building hung a sign: lawyer Jürgen Dreves. Well, it stuck in my head. And when, after returning to the Berlin office, they told me I needed to prepare documents… I said: prepare me documents on such-and-such a person.”

Ultimately, thanks to a successful scheme, Moscow managed to establish that Fischer was alive and behaving in the most dignified manner. And for Drozdov-Dreves, this operation ended just like at the end of the film “Dead Season”: on February 10, 1962, on the Glienicke Bridge on the border between West and East Berlin, Yuri Drozdov personally met Fischer-Abel, exhausted by American prison, who had been exchanged for the American pilot Powers, convicted in the Soviet Union.

After returning from Germany in December 1963, Drozdov was offered the opportunity to begin training for work in China. In the winter of 1964, he recalls, “I was summoned to the Center to report on work on China. After the report, the Chairman of the KGB, V.E. Semichastny, called Yuri Andropov at the CPSU Central Committee and reported that an intelligence resident from Beijing had arrived. Yuri Andropov asked that I be sent to him immediately for a conversation. I remember how he rose from the table and walked toward me with a smile… We introduced ourselves, and he asked: ‘Sit down and tell me about all your impressions you had there, in China…’ The meeting lasted about four hours. Yuri Vladimirovich knew how to listen, ask questions, was always active, and involved others who came into the office in the conversation. At the end of the conversation, I refused his offer to transfer to work in the apparatus of the CPSU Central Committee. He smiled again: “Well, think about it, think about it…”

This meeting proved fateful for Drozdov. On May 18, 1967, Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov was appointed Chairman of the KGB under the USSR Council of Ministers. The era of rebuilding the state security agencies, including foreign intelligence, destroyed and humiliated under Khrushchev, had begun. In 1968, after Drozdov’s return from China, Andropov told him, “So we’ve met, and we’ll work together.” Soon, Drozdov was summoned by Colonel General Alexander Mikhailovich Sakharovsky, the head of the First Chief Directorate, who conveyed the Chairman’s decision to appoint Drozdov deputy head of illegal intelligence and added, “Within the Directorate, you can try, search, change, do whatever you want, but Directorate ‘S’ must find its place. Yuri Andropov asked me to convey this to you.”

The fact is that the previous KGB chairmen, Shelepin and Semichastny, being Khrushchev’s protégés, hadn’t delved into intelligence and counterintelligence work, which led to failures and setbacks. To compensate for the damage they had caused, it was decided, among other things, to create a fictitious neo-Nazi organization and, through it, infiltrate the West German BND intelligence agency, exploiting the sentiments among its officers. As the Nazi “chief,” Yuri Ivanovich had to reclaim the language he had acquired during his years of work in China and Central Asia, and, under the name “Baron von Hohenstein,” go to the “site.”

A recruiting interview with one of the candidates, a BND officer, seemed like a conversation between two like-minded individuals: a German baron, a former SS officer living in exile and leading those who remained loyal to the ideals of the Reich, and a young BND officer who held similar views. “I asked,” writes Yuri Ivanovich, “if he remembered the oath that all ‘we’ swore to the Führer. He answered affirmatively. Then I simply offered to repeat it. ‘Before the Almighty Lord God! I swear! To be a loyal and courageous soldier to the Führer of the German people—Adolf Hitler!’ … Then I asked the final question: ‘Does your father remember this?’ ‘My father is ready to personally participate in the organization’s activities.'” That was enough—for a long time, the Center continued to receive classified information from the most sensitive unit of West German intelligence.

Andropov, who, incidentally, was on the party register at Directorate “S,” closely monitored the operation’s progress. Once, in a conversation with Drozdov, he joked that after retirement, “the two of us will write an entertaining script for an adventure film.”

In early 1975, Directorate “S” Chief Vadim Alekseevich Kirpichenko and his deputy Yuri Ivanovich Drozdov were debriefing with the head of the First Chief Directorate, Vladimir Aleksandrovich Kryuchkov, when Kryuchkov suddenly said, “Yuri Ivanovich, what do you think about working in New York? You’ve been home for almost six years now. Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov wants you to replace Boris Aleksandrovich Solomatin there.”

Under the cover of his position as Deputy Permanent Representative of the USSR to the UN, Drozdov became head of the New York station for foreign intelligence. In the early autumn of 1979, he received a telegram instructing him to return to Moscow to his previous position. “A few days after my return, I had a meeting with KGB Chairman Yuri V. Andropov,” recounts Yuri Ivanovich. “He said that the KGB leadership had decided to make changes to its plans for my use.” “Kirpichenko is being transferred to another job. By the way, he’s currently on a business trip. And we’re offering you the position of head of Directorate “S,” especially since you’ve risen from rank and file to deputy head, and you know everything about it…” Kryuchkov, who was present at the conversation, asked me to pay attention to Afghanistan. After the conversation with Andropov, I returned to my office, No. 655, on Lubyanka Square.

Directorate “S”‘s primary mission remained active reconnaissance to prevent a surprise nuclear missile attack on the USSR. It was essential to discard everything the enemy had learned from traitors and failures, and constantly seek out new, bold, and daring approaches, never forgetting secrecy and diversionary maneuvers.

In the early 1980s, in connection with the deployment of Pershing-2 medium-range ballistic missiles in Europe, the Vartanyans, Soviet illegals working in Italy under the guise of wealthy merchants, underwent retraining in Moscow and learned German in eight months. Through their connections, they were able to obtain information on the organization, combat strength, deployment, and armament of NATO bases in Europe, as well as the locations and construction plans of missile sites and nuclear weapons storage facilities. As a result of the information received from them, the Soviet side took retaliatory steps, which led to the signing of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in December 1987.

In 1984, Gevork Andreevich Vartanyan was awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union. Here’s how he describes it: “They issued a certificate here in Moscow, with different documents and a name, so it wouldn’t leak anywhere. My wife, Goar Levonovna, was awarded the Order of the Red Banner. When we were informed of this, we gathered quickly, energetically, and ordered excellent wine at a restaurant. The joy was enormous and unexpected. No one hinted at it, not even a word! I later guessed that a lot of this was due to Yuri Ivanovich Drozdov. And Goar and I thought we’d worked for so many years. We’d crossed sixty. It wasn’t that we were tired, but we decided that it was time to stop wandering when that age was approaching. And during our next vacation, when we came here in 1984, we asked to quietly return. Back then, Chebrikov, Kryuchkov, and Drozdov were in charge of intelligence. We were given permission, a couple of years to quietly wrap things up. And we returned. Thank God, we had no failures. If an intelligence officer, including an illegal intelligence officer, observes all necessary security and secrecy measures and conducts himself appropriately in society, no counterintelligence agency will ever detect him. My wife and I, having worked abroad for many years without incident, are a clear example of this.”

As early as the mid-1960s, the KGB leadership, thanks in part to the advice of Generals Sudoplatov and Eitingon, who had served time in the Vladimir Central Prison, concluded that in the event of war, the weak point in conducting guerrilla operations behind enemy lines lay in the training of special forces group commanders and reconnaissance and sabotage operatives.

At Andropov’s initiative, on March 19, 1969, the USSR Council of Ministers signed a decree establishing the KUOS (Officer Advanced Training Course), headed by front-line soldier Colonel Grigory Ivanovich Boyarinov. This had a positive impact on the combat missions of the Zenit, Kaskad, and Omega special forces groups in Afghanistan from 1979 to 1984. These groups, as later the Vympel GSN, were primarily or largely staffed by KUOS graduates.

On December 19, 1979, the head of Directorate “S”, Major General Yuri Ivanovich Drozdov, flew to Kabul and personally tasked the Zenit and Grom groups with storming the Taj Bek Palace, which they took on December 27 in 43 minutes, which meant a change of political regime in the entire country — an unprecedented event in the history of the special services.

Reporting these results to Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov on December 31, Drozdov proposed, based on the experience gained, creating a special unit within the KGB’s underground intelligence system with the same functions, but on a permanent basis. After lengthy negotiations, the Central Committee of the CPSU and the Council of Ministers of the USSR issued classified Resolution No.719-204 on July 25, 1981. Based on this, KGB Order No. 00147 of August 19, 1981, established the Separate Training Center (STC) under the 8th Department of Directorate “S” of the First Main Directorate of the KGB of the USSR. The STC was unofficially known as the GSN “Vympel.” Its purpose was to conduct special operations outside the country during a special (threat) period, including sabotage of enemy military and industrial facilities, the creation of deep intelligence networks, the release of hostages, the elimination of enemy figures posing a threat to the state, as well as traitors, the initiation of insurgent movements and guerrilla actions, etc. Orders for such operations could only be issued by the Chairman of the KGB of the USSR.

All preparatory work for the creation of the Vympel GSN was entrusted to the deputy heads of the 8th Department: Alexander Ivanovich Lazarenko, Ivan Pavlovich Evtodyev, and Yevgeny Aleksandrovich Savintsev, assisted by Valery Vladimirovich Popov, now president of the Vympel Group Association. Captain 1st Rank Evald Grigoryevich Kozlov, a participant in the storming of the Taj Beg Palace and Hero of the Soviet Union, was appointed Vympel’s first commander.

According to Yuri Ivanovich Drozdov, Vympel could be called a “special forces reconnaissance unit.” Like Sudoplatov’s OMSBON, they recruited only volunteers. Their names were never revealed. They received their awards behind closed doors. Their lives were a secret even to their families. Much attention was paid to psychological training. For example, some Vympel employees illegally “trained” in NATO special forces units. Everyone spoke at least two languages, and many had two or three higher education degrees. However, as Yuri Ivanovich noted, training in, say, hand-to-hand combat, for everyone without exception took place not on a soft carpet, but on asphalt.

On the eve of Yuri Ivanovich Drozdov’s 100th birthday, this author met with Colonel Ivan Pavlovich Evtodyev, an honorary member of the state security service who served under Pavel Anatolyevich Sudoplatov and knew all the heads of the underground intelligence service. According to Ivan Pavlovich, who turns 101 this year, Yuri Ivanovich Drozdov was a highly educated and talented man. He was distinguished, above all, by his enormous self-discipline. “He was strict with himself and demanded the same from others.” Furthermore, his determination should be noted—once a task was set, the plan was worked out down to the last detail.

Another trait of his was his exceptional work ethic. He had a desire to fully understand people—who was suited for what job. At the same time, Yuri Ivanovich himself was an emotional person, although he hid it. “He was very upset by Boyarinov’s death,” says Ivan Pavlovich. “He went to the KGB Higher School to say goodbye to him, stood by the coffin for over 20 minutes without saying a word—just so you understand, I went with him. On the way back, he said to me, ‘If you’re going to speak at the funeral, choose warmer words.’ He himself didn’t attend the funeral; it was very difficult for him. Boyarinov was posthumously awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union.

Another time, when Belyuzhenko was in the hospital, Yuri Ivanovich also took me along—to congratulate Belyuzhenko on his title Hero of the Soviet Union. Belyuzhenko was in serious condition, and his mood was primarily depressed. He could barely speak. Yuri Ivanovich found the right words, gradually got him talking, and we stayed there for about an hour and a half. When we left, Belyuzhenko was smiling. It’s absolutely true—Drozdov had a talent for influencing people. Perhaps not to the same extent as Sudoplatov, but certainly no less than Korotkov. While Korotkov could be rude and arrogant, Yuri Ivanovich never raised his voice or used harsh language. As for work, they were equals—I’m not counting Sudoplatov, he’s unmatched. But I’d go into intelligence with the others, too, including Lazarev and Kirpichenko. They were all very strong leaders.

I worked for Yuri Ivanovich for five years, from 1979 to 1984, and for about a year, I visited his office twice a day—when the Afghan conflict began and when the Vympel group was being created.”

There’s no doubt that Yuri Ivanovich Drozdov would have continued to work just as productively if not for the events of 1991. Yeltsin, who came to power, liquidated both Vympel and the 8th Department, opening NATO a direct path to the east.

That’s what Yuri Ivanovich Drozdov was, the most legal of illegals—and that’s how he will remain in our memory.