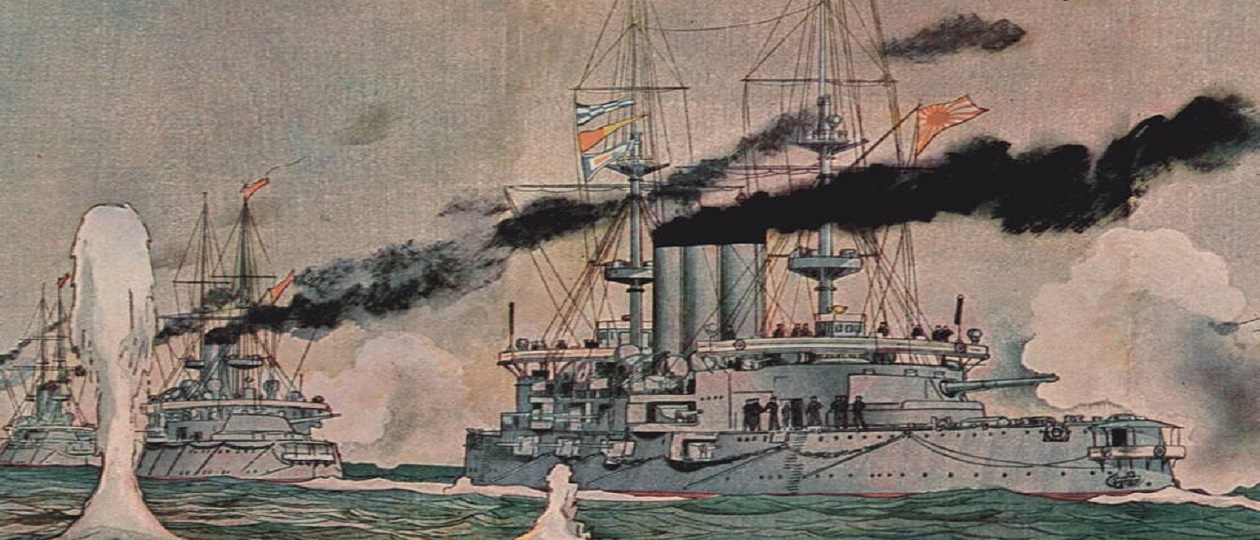

In June 1905, The Chronicle of the War with Japan weekly, published in Russia’s capital, ran this: “It can be said without any doubt that espionage has never been practiced in previous wars on such a large scale as it is being used now by our enemy in the Far East. The Japanese have flooded the area, occupied by our armies, with hundreds of spies who are in our bivouacs, hospitals, railway stations – everywhere.”

One of the best Russian writers of that era, Alexander Kuprin, dedicated his masterpiece story “Staff Captain Rybnikov” to a Japanese intelligence officer who operated very successfully in St.Petersburg. Some modern researchers believe that his prototype was Baron Motojiro Akashi. His flamboyant exploits, both real and imagined, became the subject of countless novels, movies and documentary programs in Japan, too, where he was dubbed the “Japanese James Bond”.

In 1900, Akashi, a high ranking officer of the Japanese Secret Intelligence Services, was sent as a roaming military attaché to Europe. There, he managed to set up an intricate espionage network in major European cities, using specially trained operatives under various covers, members of locally based Japanese merchants and workers, and local citizens either sympathetic to Japan, or willing to cooperate for a price.

Two years later Akashi arrived in Russia’s capital as a Japanese military attaché. He had a discretionary budget of 1 million yen (an incredible sum of money in contemporary terms) to gather information on Russian troop movements, naval developments, and to support Russian extremists. He reportedly recruited the famous spy Sidney Reilly and sent him to Port Arthur, to gather information on the Russian stronghold’s defenses where my grandfather, Pyotr Vassilievich Korchagin, served at the 3rd Eastern Siberian rifle brigade.

When the war with Russia started, Akashi moved to Stockholm, but did not cease his previous activities. He traveled across Europe, collecting information and organizing subversive activities against the Russian Empire, using his contacts and network to seek out and to provide monetary and weaponry support to extremist forces attempting to overthrow the Romanov dynasty. Fluent in various European languages but Russian, Akashi found a common language with Russian Social Democrats and Socialist Revolutionaries, Polish, Finnish, Baltic and Caucasian nationalists, and revolutionary-minded youth.

Personally and through his assistants, he recruited high-ranking officials, officers, employees of military factories and ports, maintained contacts with prominent Russian personalities, involved in subversive activities, like priest Gapon and the famous adventurer Azef, courted the future head of the Polish government, Józef Pilsudski.

Despite winning battles at sea and on land, the Japanese General Staff was seriously concerned about the outcome of the war. Russia had incomparably greater economic power, natural and human resources, while the Japanese economy was on the verge of collapse, and the treasury was exhausted. Akashi proposed arming Russian revolutionaries, inciting them to revolt in the European part of Russia and thereby distracting the authorities’ attention from the Far East.

In July 1904, Akashi met with the leaders of the Russian Social Democrats Plekhanov and Lenin in Geneva. In his previous activities report to Tokyo he said: “In my opinion, Lenin is a sincere person, devoid of egoism. He is capable of causing a revolution.” That same year, Akashi sponsored a conference of Russian opposition parties in Paris, and a year later, in Geneva. Also, on two occasions he organized the purchase and delivery of large quantities of weapons to Russian revolutionaries.

In January 1905, Russia’s Minister of War received a report from Paris: “The Japanese government distributed 18 million rubles to Russian revolutionary socialists, liberals, and workers to organize unrest in Russia by destroying naval factories, making it impossible to send the Baltic and Black Sea squadrons to the Far East, starving Kuropatkin’s army in Manchuria, and by forcing Russia’s Government to conclude peace with Japan.”

In 1907, Akashi returned to his homeland, where the emperor granted him the rank of Major General and the honorary title of Baron. Also, he got the highest awards of the Japanese Empire. Soon afterwards Akashi headed the military police in Korea, at the end of 1913 he received the rank of Lieutenant General, and 6 months later he was made deputy chief of the General Staff.

Akashi’s fellow spy and close friend, General Fukushima Yasumasa, also made a significant contribution to Japan’s victory in that war. Born into a samurai family, he was engaged in intelligence activities from his early years. At the age of 24, he became a military attaché in the United States, then in China, and then in Germany. He returned to his homeland on horseback, having galloped 8,700 miles in 504 days from Berlin to St.Petersburg-Moscow-Urals-Irkutsk-Vladivostok. There Fukushima turned south and reached Japan through Manchuria, Mongolia and China.

He did all that allegedly on a bet, having made a bet in Germany’s capital with a group of cavalry officers, including Russia’s military attaché. In reality, on his way across Russia Fukushima studied the terrain, roads, local population’s mores, construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway and, in general, everything that could be useful to the Japanese army.

In 1944, when the USSR began preparations for a new war with Japan, the Main Directorate of the Soviet Security Forces issued a secret collection of documents on Japanese espionage in Tsarist Russia. One of those documents said: “Disguised officers of Japan’s General Staff did not disdain to keep brothels, engage in crafts, perform lackey and cook duties for Russian arisctocracy. Agents, recruited from local population, included paramedics, Chinese magicians and healers, merchants and wandering musicians, owner of an American brothel in Vladivostok (a favorite place for all types of military personnel). The Japanese had secret agents in all of important points of the war theater, plus some distant provinces of Russia.”

In Manchuria the Japanese recruited spies among local population, using blackmail and taking hostages. To quote The Chronicle of the War with Japan once again, “The Japanese have a whole network of well-organized spies, easily recruited from local population. During the battle on the Shahe River, the Chinese were watching us closely which resulted in enemy’s amazingly accurate shots at our trenches and batteries.”

British writer Story, who was with the Russian army during the first half of the war, noted: “The success of Japan depends on its remarkable espionage system. Its close collaboration with Chinese population caused the Russians more losses than the Japanese military strategy.”