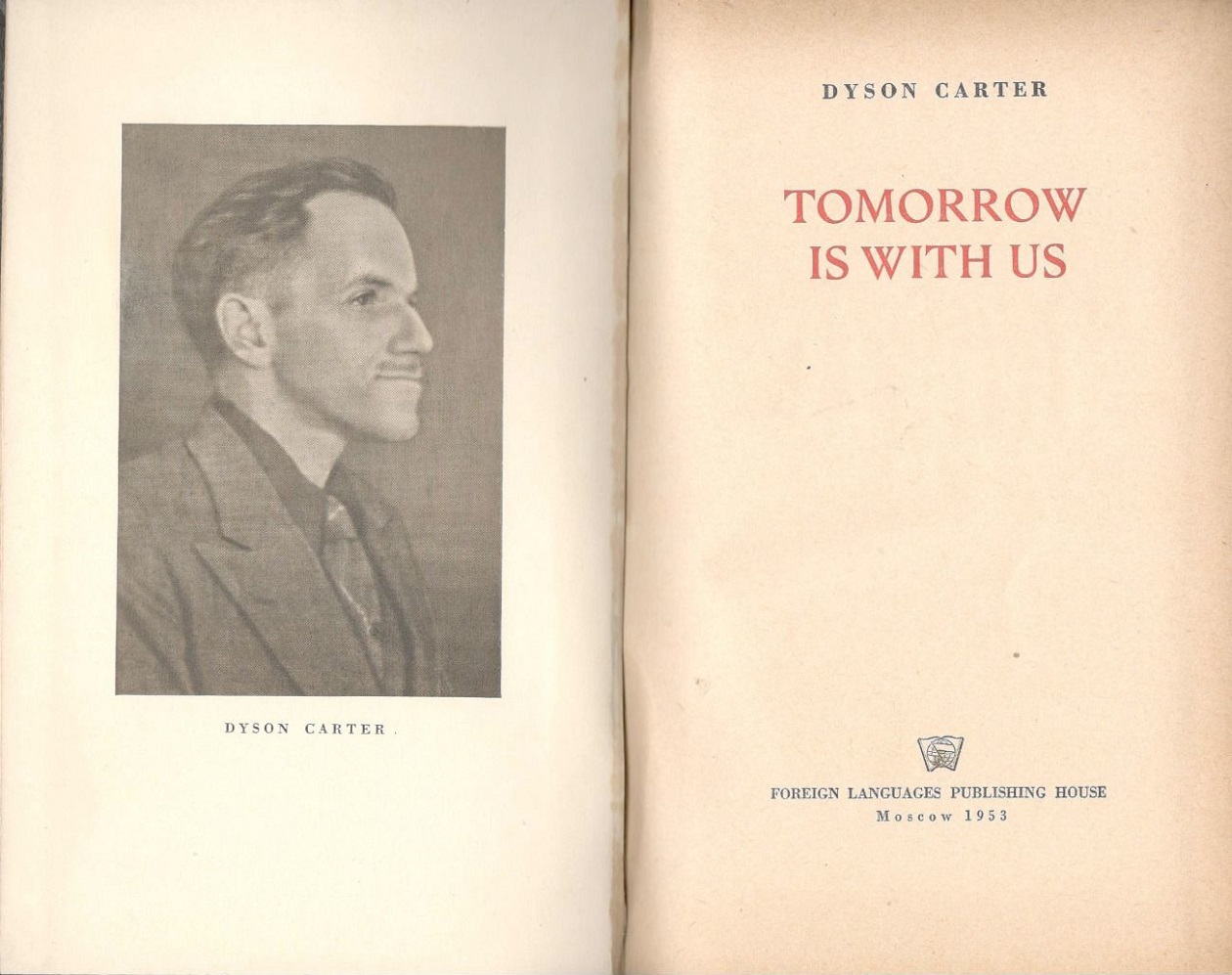

Perestroika, among other things, led to the severance of ties with millions of foreign friends, many of whom devoted their entire lives to establishing normal relations with our people. Among them was the Canadian writer, scientist, educator and publisher Dyson Carter (1910-1996).

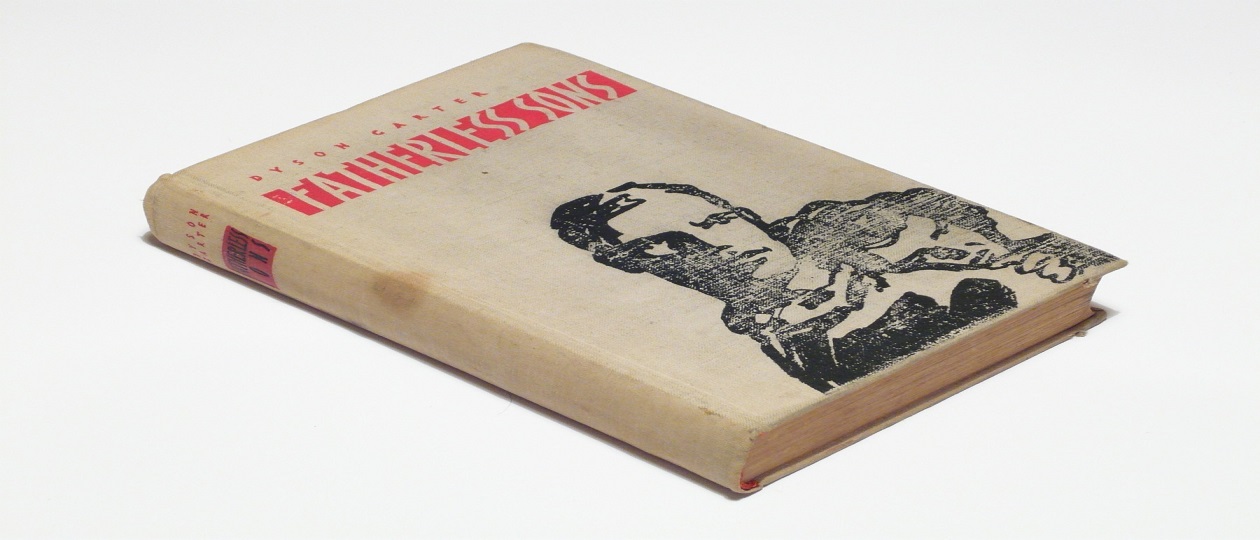

“During his fifty-plus years of writing, Dyson Carter published hundreds of magazine and newspaper articles, dozens of short stories and 17 books, including five novels,” says an article by an expert on his work, James Doyle Science, Literature And Revoluion: The Life And Writings of Dyson Carter. “In the 1930s and 40s, his articles and short stories appeared in prominent newspapers and magazines published in Canada and the United States, and three of his early works were printed by American commercial publishers, earning many laudatory reviews.”

Carter gained international fame at the beginning of World War II, publishing the book Sea of Destiny: The Story of Hudson Bay, Our Undefended Back Door. In it, he warned of the danger of a Nazi invasion of Canada through the ice-free Hudson Bay.

Two years later, his first novel, Night of Flame, was published, which was noticed and duly praised by The New York Times and Toronto’s The Globe and Mail. The literary critic of another Canadian newspaper, The Ottawa Citizen, wrote that the debutant was “only one step away from being recognized as a genius.” However, J. Doyle writes that, unlike other Canadian writers of such caliber, Carter was not honored with even a cursory mention in reference books on the literature of the Land of the Maple Leaf, since he “was a member of the Communist Party of Canada and fell victim to the collective hostility and amnesia that engulfed Canadians during the Cold War.”

While World War II was going on and the Soviet Union was considered an ally of the Anglo-Saxons, Night of Flame was published and republished under the author’s name. But as soon as the spirit of McCarthyism began to blow, the largest American publishing house, Signet, behaved in accordance with the proverb “I want to, but I don’t want to”: wanting to make money on the reprint of a bestseller and at the same time fearing accusations of sympathy for a member of the Communist Party, it published Dyson Carter’s book under the pseudonym Warren Desmond.

Carter, in the midst of McCarthyism, headed the Canadian-Soviet Friendship Society and visited our country, sharing his impressions in the books We Saw Socialism and World’s Hope. In another of his works, Big Lie, he exposed another slanderous campaign by the United States against the USSR. At the same time, he began publishing the magazine News-Facts About the USSR, later renamed Northern Neighbors. A unique publication (it was entirely devoted to Soviet reality), by 1985 it had gained 10 thousand subscribers in Canada, the United States and 79 other countries on all continents.

Since the early 1960s, Carter maintained close contact with the Novosti News Agency (NNA) and from time to time sent his correspondence on international topics to Moscow. They were prepared for publication by Nellie S. Working in the main Soviet department of foreign policy propaganda, she did not hide her sentiments, typical of those representatives of the creative intelligentsia with closet dissent. As soon as Nellie S. got hold of Carter’s article, she began to snort sarcastically: like, this Canadian has completely lost his mind, admiring our country.

Defending the interests of the USSR at his own risk and peril in his homeland, Dyson Carter did not find understanding and sympathy from his curator at APN. In September 1973, I began working in Canada as a special correspondent for NNA and two months later I met Carter at a reception in our embassy on the occasion of the 56th anniversary of the October Revolution. Before this, I had been warned: I had to be extremely careful with him — he had suffered from “crystal man syndrome” since childhood, and even a strong handshake threatened him with another fracture, which Dyson had lost count of in his youth.

And then I saw: among the guests appeared an elderly woman with a wheelchair, and in it — a gray-haired man with a big forehead, slightly taller than a dwarf. Dressed in a strict dark suit, the face of a typical character from English films of the middle of the last century. These were Dyson Carter and his wife Irja.

I introduced myself, carefully, as I was advised, took Dyson’s palm in my hands, and between us, as writers sometimes say, a spark immediately ran, striking an unquenchable fire of long-standing friendship. When Carter turned 65 in 1975 and I decided to congratulate him with an essay in the magazine Soviet Union Today (published by our embassy in Canada), I did not have to pore over a typewriter in a painful search for the right words — they fell on the page by themselves, because they came from the heart.

Carter’s outlook, his scope and understanding of the events that were taking place were phenomenal. Living almost constantly in the middle of nowhere, being cut off from the outside world also due to his deafness, he nevertheless amazed me with the depth of his thoughts and unusually accurate characterizations.

On March 8, 1979, my assignment to the Land of the Maple Leaf ended. Before that, Dyson sent me a New Year’s greeting with a wish for a happy return to the Motherland and an expression of hope for new meetings. Such a meeting took place in the summer of 1980 in Moscow, where Carter became the first Canadian knight of our Order of Friendship of Peoples. And a year later I was sent overseas again – as a Washington correspondent for Izvestia.

From there, I called Dyson from time to time and a couple of times ordered articles from him for Izvestia. Carter was sincerely glad that our contacts continued. The last letter from Dyson that I have preserved is dated April 1983. It spoke of the growing anti-war sentiment that had reached Gravenhurst, the small village where the Carters lived: “People in our area have become ardent supporters of the anti-nuclear war movement. They have even won the right to put up a poster at the entrance to Gravenhurst saying ‘We are for peace’! And yet the people who inhabit our rural area have always been extremely conservative.”

Perestroika, however, also had the most tragic effect on the fate of Dyson Carter. What was it like for this brave man, who, at the height of the persecution of people with leftist views, was not afraid to head the Canada-USSR Friendship Association, and then for more than 30 years acquainted his readers and subscribers to “Northern Neighbors” with the achievements of our country — what was it like for him to suddenly learn that in Soviet history textbooks, as one of the foremen of perestroika, Yuri Afanasyev, stated, there was supposedly “not a single truthful page”? But this was carried and spread more and more powerfully throughout the world, not only from the lips of the former mentor of the national pioneers and Komsomol. Afanasyev had a whole host of accomplices, headed by the ideologist of perestroika, Alexander Nikolaevich Yakovlev.

In December 1989, Dyson Carter, depressed by what was happening, stopped publishing “Northern Neighbors”. The most devoted friend of the Soviet people and state considered himself betrayed. “It turns out that I have been spreading bullshit for forty years,” he wrote in despair to his old friend John Boyde.

In the spring of 1992, Igor L., who had headed the APN Bureau in Ottawa for several years, returned to Moscow from Canada.

— How is Dyson? — I asked him.

Igor only waved his hand in frustration:

— Having closed his magazine, he flatly refused to see Soviet representatives.