As I mentioned in Part 1 of this article, in 1973 I started working as a reporter in Canada. There, and later on in USA, I experienced a real shock to find out how little local people knew about other nations, their culture and history.

In 1950s my father worked at Goslitizdat, the biggest Soviet publishing house where he managed the department of foreign literature. He acted as editor compiler of books written by Chile’s Nobel Prize winner Pablo Neruda, France’s Jacques Prevert, Cuba’s Nicolas Guillen, Turkey’s Nazym Hikmet, Bangladesh’s Jasim Uddin, best poets of Egypt, Vietnam, China, Myanmar. These books used to be published in the USSR in many thousands of volumes and were available in bookstores and libraries across the whole country.

Similarly, my father’s colleagues were responsible for translation and publication of Western literature. As a result I got a chance to read Ernest Hemingway’s Farewell to Arms, Erich Remarque’s Three Comrades and Saint Exupery’s Little Prince even before I graduated from school. A bit later I enjoyed Jerome Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye, Francoise Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse, Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage, to name just a few.

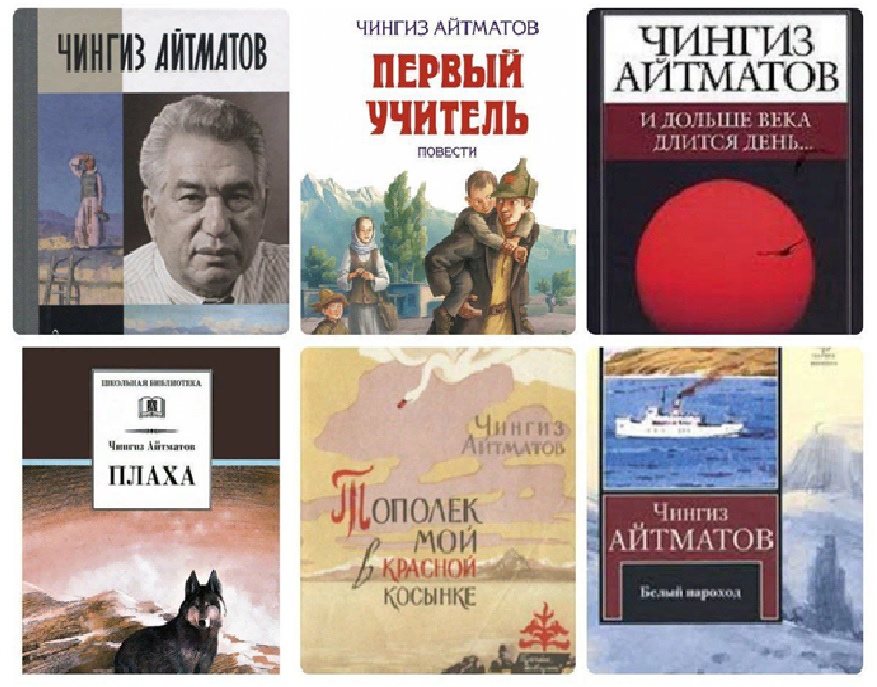

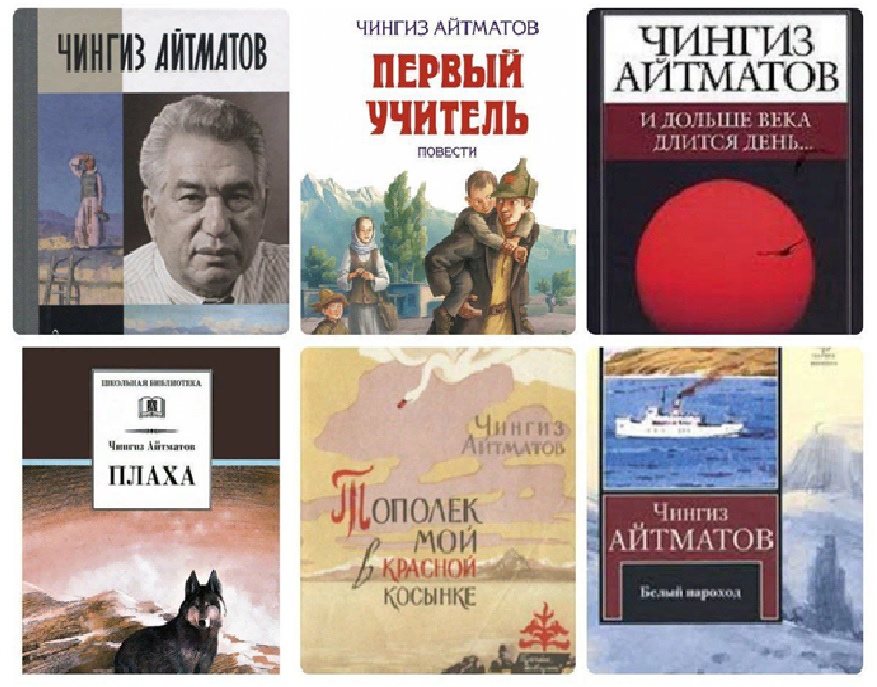

Two years later, Chingiz Aitmatov, one of the best Soviet writers, paid a visit to Canada. Author of numerous novels and short stories, by that time he had gained acknowledgement in some European countries. In early 1960s, the London-based magazine Central Asian Review ran an article about him, while his novels The White Steamship and Farewell, Gulsary! were translated into English.

In Canada Aitmatov spent 10 days. He was a guest speaker at the Faculty of Slavic Philology and Islamic Studies in the famous McGill University and met with the federal Minister of Culture Hugh Faulkner, local writers, poets, playwrights, literary critics and simply lovers of fine literature. At these meetings Aitmatov spoke about the need to strengthen bilateral cultural ties by publication of translated literary works. All he got back were nice smiles and a few rounds of polite applauses. Not a single Canadian publisher displayed any interest in his books.

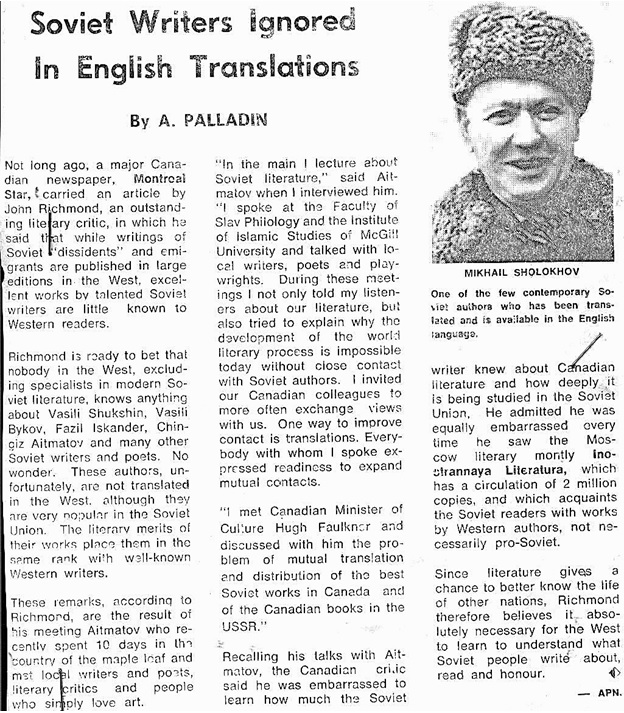

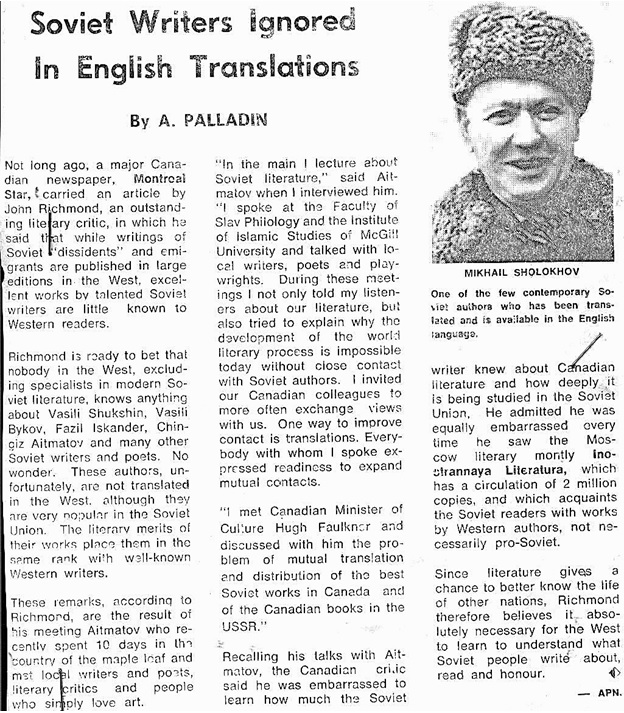

Soon after Aitmatov went back home, John Richmond, one of the literary critics he had met, published an article in The Montreal Star. In it he pointed out the main reason why Aitmatov had been treated that way. According to Richmond, in the West, only books of Soviet dissidents and correspondingly minded emigrants were willingly published in large, sometimes enormous print runs, while truly outstanding works of the most talented writers and poets from the USSR remained unknown to the Western public.

I bet, Richmond emphasized, that in North America no one, except for a very narrow circle of experts and enthusiasts, had ever heard of Vasily Shukshin, Fazil Iskander, Vasil Bykov, Chingiz Aitmatov or any other Soviet writer. One of the false pretexts for Soviet literature cancellation was that it was full of facts and details of everyday life of people belonging to an alien civilization, requiring lengthy explanations.

Richmond added that his conversation with Aitmatov made him feel ashamed because the Soviet writer demonstrated a solid knowledge of Canadian literature. Besides, the Canadian literary critic was stunned to learn about the Soviet magazine, Foreign Literature, with a circulation of 2 million copies, which introduced citizens of the USSR to new foreign fiction on a monthly basis.

Later on, working as Washington Bureau Chief of Izvestia, I took part in numerous TV and radio debates with high-ranking American dignitaries, leading journalists and political scientists. One of their favorite topics was freedom of speech. Curiously, whenever I asked them to name at least one book by a Soviet writer or poet they would only mention Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago.

Once I engaged in a verbal duel with President Reagan’s buddy, the head of US Agitprop, Charles Wick. He, too, began to sing the standard song about the presumed lack of freedom of speech and press in the USSR. In response, I said, “Sir, as I do not want to embarrass you I will not ask you the same question that stumps my American opponents each time they start such a debate.” As on so many occasions before that, it worked: Wick quickly changed the conversation to another topic.