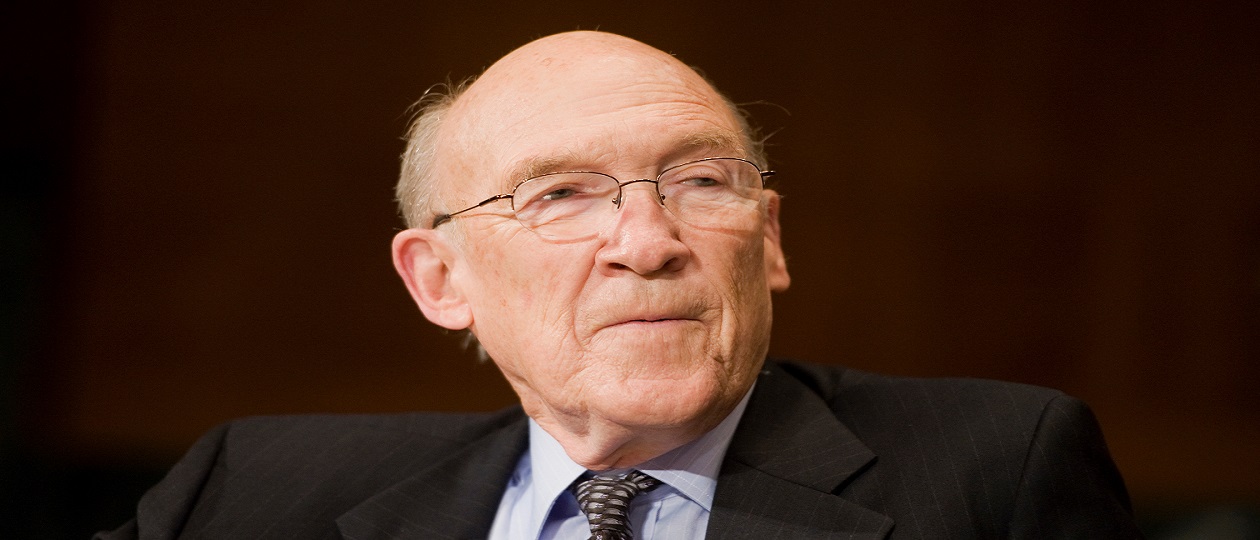

In loving memory of my very dear 6-foot-7-inch Republican senator friend.

My old friend Senator Alan Simpson died this morning. He was 93.

Our friendship began at one of those interminable Washington receptions I had grown to hate. They were always stand-up events where I was expected to engage in small talk with dozens if not hundreds of people I didn’t know, moving among groups while trying to balance a drink with a napkin containing cheese puffs or tiny cucumber sandwiches, and shaking hands as if enjoying myself.

The hardest part was deciphering what people were saying to me because their voices emanated a foot or more above my ears and the ballrooms were invariably noisy. When encircled by the taller-than-normal men who tended to be senators and members of Congress, I felt as if I’d fallen into a well.

At this particular reception, a senior senator on the Judiciary Committee began telling me something with apparent glee, but he was so very tall and the crowd so noisy that I couldn’t hear a word. So I grabbed a nearby chair and stood on it, which put our heads at about the same level.

“I’m Alan Simpson,” he said, with great amusement.

“Well, Senator, I’m Robert Reich, and I’m glad to be up here in the stratosphere with you.” We shook hands.

“A bit dizzying up here, isn’t it?” He laughed.

“Better than down there, where I can’t hear a damn thing and get spit on.”

“I’d never spit on a cabinet member, not even a Democrat,” he said, with mock seriousness.

“Not intentionally, but you’d be surprised how much saliva rains down there. I almost need an umbrella.”

By this time several attendees had gathered around us, amused that the extremely tall Republican senator and unusually short Democratic secretary had found common ground.

Everything I had learned about Simpson suggested we occupied the opposite extremes of Washington. He was a conservative Republican from Wyoming, a fiscal hawk, close friend of George H. W. Bush, chum of Dick Cheney and George W. Bush, and six-foot-seven. He had served in the Wyoming legislature for thirteen years after being elected in 1964, then been a three-term U.S. senator starting with his election in 1978.

Yet within minutes of standing next to him on top of a chair in the middle of that reception, I discovered we had something in common: our senses of humor. He told me that his mother was over a hundred and fit as a fiddle because she walked five miles a day. “The only problem is we have no idea where she is,” he deadpanned. I almost fell off my chair.

I asked him if he knew the difference between congressional politics and university politics. “No, tell me!” he asked with a broad grin. “In Congress, it’s dog-eat-dog,” I explained. “In university politics, it’s exactly the opposite.” He cracked up.

“We have two political parties in this country,” he said. “One is the Stupid Party, the other is the Evil Party. I belong to the Stupid Party,” he laughed.

“You’re very funny,” I said.

“You’re very funny, too.” he said. “You always seem very serious when I see you on the news.”

“CNN doesn’t appreciate shtick.”

“What’s shtick?”

“You seriously don’t know?”

“No.”

“Cow dung on a stick.”

He exploded in laughter.

I told him that I took my job very seriously but tried not to take myself too seriously. He said he did the same, but most of his colleagues did the reverse. He then told me about his family, and I told him about mine. We both missed our kids, another point of connection.

We resolved to meet for lunch.

When I returned to the Labor Department and asked my assistant to arrange it, she demurred. “You haven’t had lunch with most Democratic senators. If you have lunch with Simpson they’ll be insulted,” she warned. She informed my chief of staff, who was even more determined that I not lunch with Simpson. “You haven’t even had lunch with Ted Kennedy!” she said. “Besides, it would be wrong. Republicans hate us. What would people think?”

Simpson’s staff was against our lunch, too (he later told me). They said it was inappropriate for a senior Republican senator from one of the most conservative states in the nation to have lunch with the most liberal member of Clinton’s cabinet. “Your constituents in Wyoming will have a fit,” they told him.

We snuck out for lunch. Neither of our staffs knew where we’d gone. Alan suggested a bistro at some distance from the Capitol and the Labor Department where we wouldn’t be found. We spent hours sharing personal stories, laughing, talking about our families. It was the start of a beautiful friendship. When I think of the poisoned politics of our time, when Republicans and Democrats often loathe one another, I’m grateful for Alan.

In subsequent months and years we saw quite a lot of each other. It was an illicit relationship by the emerging norms of Washington, but we didn’t care. After I left the administration and Alan retired from the Senate and accepted a temporary position at the Kennedy School’s Institute of Politics, we grew even closer. We did a public television show together on Boston’s WGBH where we discussed the issues of the week for thirty minutes, mixing humor and politics. We called it “The Long and the Short of It.” We began each episode by walking toward each other from opposite sides of the stage set, in silhouette—Alan’s long, lanky frame almost entirely filling one side of it and my stubby one filling barely two-thirds—and shaking hands before sitting down, when the stage lights would go on and we’d go at it. We often disagreed on the issues but did it with so much warmth and evident enjoyment of each other’s company that many people wrote in to say they loved watching us because we were such a relief from the usual political fare. The show lasted only one season, but we had a wonderful time doing it.

We also appeared in various forums, such as the institute run by Leon and Sylvia Panetta in Carmel, California. On these occasions, Alan and I often shared regrets about what was happening to American politics. “They hate each other,” he said, of the crop of Democrats and Gingrich Republicans who followed us into Washington.

When Trump first ran for president in 2016, I asked Alan why he thought more Republicans weren’t speaking out against Trump. “They’re scared,” he said.

“Scared of Trump?”

“No,” he said, lowering his voice. “They’re scared of the kind of people Trump is attracting and what he’s bringing out in them.”

“You mean, they’re scared of being physically harmed?”

“Friend, it only takes one nutcase.”

Alan had become a controversial figure among Trump Republicans for his liberal views on women’s rights and gay rights. He had long been controversial among liberals and Democrats for other positions he took. He served on the Senate Judiciary Committee that skewered Anita Hill and confirmed Clarence Thomas.

As the Republican co-chair of Obama’s commission on the federal deficit, he called Social Security recipients “greedy geezers.” When California’s Alliance for Retired Americans protested one of his appearances in the state, he called their view “a nefarious bunch of crap.” In an email to an official of the Older Women’s League who complained that he wanted to cut Social Security, he compared the program to “a milk cow with 310 million tits,” and ended with “call when you get honest work.”

He made some errors, but I admired his sincerity and passion for democracy. Alan wasn’t in anyone’s pocket, and he bemoaned the role of big money in politics. “If this crap continues,” he told me one day when we were doing “The Long and the Short of It,” “in a few years, some wealthy bozo is gonna buy the whole damn presidency. It’s ludicrous.”

The last time we spoke was when I phoned to congratulate him on being awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Biden.

“I saw it was you calling,” he said. “I wouldn’t have answered if it was anyone else.”

“Congratulations, Alan,” I said. “You could be the last Republican in the United States with any sense of civic responsibility.”

“No,” he said. “Just up the road from where we live is a Republican cow. Very responsible. Doesn’t shit anywhere outside her pasture.”

Alan Simpson, my dear friend, may you rest in peace.