Russia’s Ded Moroz (Grandpa Frost) has a close relative in the Western world. His name is Santa Claus, also known as Saint Nicholas.

They both have the same gentle, kind characters and similar duties, i.e. to deliver gifts to children and

to amuse people at large.

What makes them different, though, is their names, different sleighs, pulled by three horses for Ded Moroz while Santa Claus drives nine reindeers, plus the fact that Ded Moroz is accompanied by Snow Maiden while Santa Claus is single.

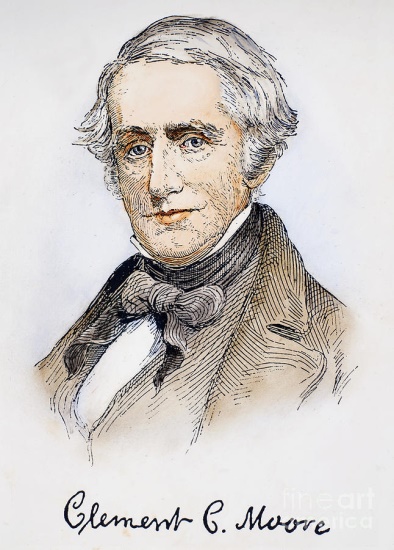

Still another distinction is their origin. Being a product of popular myths, Ded Moroz, so to say, is fatherless, while Santa was created by American writer and scholar Clement Clarke Moore.

Moore, a professor of Oriental and Greek literature from New York, is said to have composed “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (also known as “The Night Before Christmas”) poem for his children on a snowy winter’s day after a shopping trip on sleigh.

His inspiration for the character of Santa was a local Dutch handyman as well as the historic Saint Nicholas.

Moore’s wife showed the poem to a family friend, who sent it to a New York State newspaper. On December 23, 1823, it published this piece without mentioning the author. Later, the poem was copied anonymously by other publications until 1837 when it was bylined by Moore’s name for the first time.

However he claimed its authorship only seven years later by including “A Visit from St. Nicholas” into his collection of poems. Before that, Moore did not want to spoil his reputation of a solid scholar by associating his name with a “frivolous” piece of work.

Anyway the poem had a very strong influence on the perception of Santa Claus throughout the English-speaking world. Some researchers even call it the best known verses written by an American.

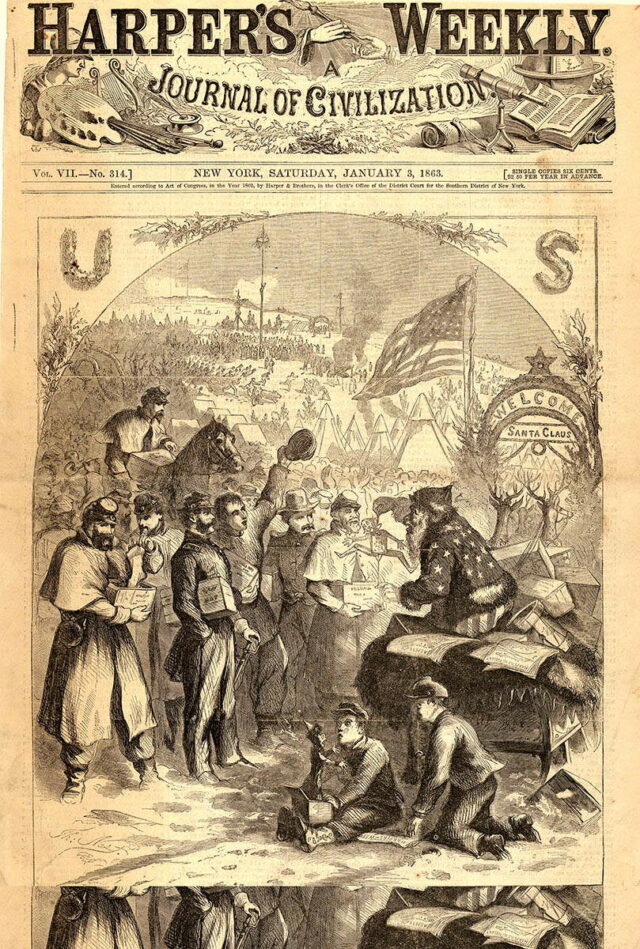

On the other hand, it took 39 years after the initial publication of “A Visit from St. Nicholas” for its protagonist to acquire an iconic image. In late 1862, the American Harper’s Weekly magazine commissioned a “portrait” of Santa Claus from a Bavaria-born artist Thomas Nast who immigrated to the USA in his childhood.

A strong supporter of the Republican party, African-American rights, and abolitionism, Nast is credited with having originated the American political cartoon. He created or popularized the now-familiar images of the Democratic donkey, the Republican elephant, and Uncle Sam.

Nast was so enchanted by Moore’s poem that he made 33 Harper’s Christmas illustrations from 1863 through 1886, and almost all of them featured Santa. His initial January 3, 1863 cover depicted Santa Claus in a star-spangled jacket handing out presents to Union soldiers.

This image paired holiday sentiment with political messaging. Nast made it clear that Santa supported the Union, not the Confederacy. Santa showed the soldiers a jack-in-the-box hanging by a noose, and the puppet had the face of Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

In recognition of his services during the Civil War of 1861-65, Abraham Lincoln called Nast “our finest recruiting sergeant.”

In his depiction of Santa, inspired by Moore’s verses, Nast allowed himself only one liberty — he replaced the small, crooked smoking pipe mentioned in the poem with a pipe with a long clay mouthpiece, which was common in Europe at that time.

Santa Claus images made Thomas Nast rich. However, unlike Moore, he was not destined to end his days in contentment and comfort. In 1884, Nast lost almost all of his fortune, trusting the financial swindler Ferdinand Ward, who had deceived many celebrities, including former US President Ulysses Grant.

In addition, the political cartooning that had brought Nast fame and money had gone out of fashion, and he himself had lost his former ability to work due to a chronic hand disease.

In 1886 Nast stopped working for Harper’s Weekly. Two years before that he lost most of his fortune after investing in a banking and brokerage firm operated by the swindler Ferdinand Ward. Six years later Nast took control of a failing New York-based magazine, investing the rest of his capital in it, but within a few months he went broke.

In desperation, he applied for a job at the State Department and, with the support of his longtime admirer, US President Theodore Roosevelt, got an appointment as Consul General to Ecuador in South America.

Despite the meager salary, Nast agreed to go there immediately. Unfortunately, a yellow fever epidemic broke out there. Nast did his best to help others fight the scourge while still in office, but he himself could not escape it and died in Ecuador on December 7, 1902, “among flies, mosquitoes, bats, spiders and incredible filth,” as he described his last refuge on Earth.