“A few years ago, a former American intelligence officer whom I knew well, having arrived in Moscow, during dinner at a restaurant on Ostozhenka, said: ‘We know that you have had successes that you have every right to be proud of.

But time will pass, and you will gasp (if this is declassified) at what kind of agents the CIA and the State Department had at your top’” (from an interview with Yuri Drozdov, one of the heads of Soviet intelligence, in Rossiyskaya Gazeta, 31.08.2007).

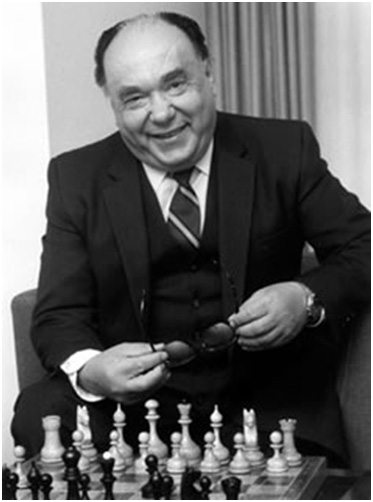

I will return to this later, but for now I will share my personal impressions from many years of communication with the “head of agitprop of all eras – from Brezhnev to Yeltsin,” as Mikhail Gorbachev once called Alexander Nikolaevich Yakovlev.

We met in Canada, where I was sent as a special correspondent for Novosti News Agency in September 1973. Three months earlier, Yakovlev had started working there as an ambassador. He was sent there as punishment for his article “Against Antihistoricism,” published in late 1972 by Literaturnaya Gazeta.

In it, the acting head of the Propaganda and Agitation Department of the Central Committee subjected the writers of the nativist movement to devastating criticism, accusing them of glorifying traditional Russian customs. Yakovlev’s opus caused such indignation that the party leadership decided to exile the head of Agitprop, who had worked in this system for 20 years, as far away as possible.

The final verdict on Yakovlev was delivered by Brezhnev: “This asshole wants to set us at odds with the intelligentsia.” The tradition of transferring disgraced dignitaries to work abroad was started by Khrushchev, who sent the former head of the Soviet government Molotov as ambassador to Mongolia.

Yakovlev was lucky in this regard. At first, he impressed me as a wise, broad-minded person. Having learned that the reason for his limp was a wound he received in the war, I respected him even more.

Many years later, however, Yakovlev’s front-line biography would cause gossip, and he himself would give the reason for it, having declared that the Nazis “put four explosive bullets into me.” Reading this, seasoned front-line soldiers were amazed that he had remained alive…

Subsequent communication with the ambassador changed my perception of this man, who played a key role in the collapse of the USSR. His wounded pride became increasingly evident, especially in his comments about dignitaries like the head of the Soviet state Nikolai Podgorny, when they were also overthrown from the heights of power.

Yakovlev was tormented by the thought, I realized, that he is smarter and more worthy than any of them. It also became obvious that the future organizer of the second— after Khrushchev — anti-Stalin campaign professed Stalin’s principle “Personnel decide everything”, but in the manner of Don Corleone (remember the beginning of the film “The Godfather”?). Such an allusion is all the more appropriate, since Alexander Nikolaevich later proclaimed himself the godfather of glasnost.

In Ottawa, those who entered the ambassador’s office were met not by a strict guardian of party morals and customs, nor by a formidable arbiter of other people’s destinies, but by a good-natured native of one of the villages of the Yaroslavl province, who had retained a manner of speaking in a village manner, as if he did not have the titles of professor and doctor of science. And Alexander Nikolaevich looked simple.

Having learned that the ambassador liked to play chess, my colleague from TASS would visit him at his residence in the evenings to have a party and at the same time get instructions on how to cover Soviet-Canadian relations.

And the journalist from “Pravda” Nikolai Bragin would tag along with Alexander Nikolaevich on fishing trips for the same purposes (both large and small fish are found in abundance in the vicinity of Ottawa). As a result, information painted in the same rosy color was sent to Moscow through three channels at once, demonstrating the results of Yakovlev’s vigorous activity.

In an effort to surround himself with loyal people, in 1974 Yakovlev secured the appointment of Viktor M., whom he had involved in preparing various documents during his time as head of Agitprop, to the post of head of the Ottawa bureau of APN.

In Canada, M., a man of a purely theoretical mind and corresponding skills, had to perform the functions of the embassy press secretary: prepare and promote information materials, actively interact with local journalists. And he, getting acquainted with his deputy (there were no other employees in the embassy press department), stunned him:

— By agreement with Alexander Nikolaevich, I work at APN until lunch, after which I continue to do what I did in Moscow: write scientific papers on philosophy.

A decade passed, and the lover of sharp expressions Alexander Nikolaevich, undertaking a swift climb to the top of power, began to proclaim his statements for the entire USSR to hear, the likes of “everything that’s not forbidden is permitted”, “the most important thing is to get into a fight — and then we will figure it out” (which became a motto of Gorbachev’s reckless politics), “Only a fool never reconsiders his positions throughout his life”.

This was said by Yakovlev to excuse his role in the collapse of the USSR, which, when later the need for pretence would pass, he would be proud of:

“The group of real, not fake reformers developed — verbally, of course — the following plan: to use the authority of Lenin to strike down Stalin, Stalinism. And then, in case of success, to strike down Lenin with social democracy”.

In February 1978, the sand castle he was building in Canada collapsed. Local special services organized a setup through their employee (for several months he as passing down the information on the hostile activities of his Canadian and American colleagues against the citizens of the USSR to our resident agents) and, accusing a dozen of Soviet embassy workers of espionage, demanded their deportation.

Trying to cover up a loud scandal, the Kremlin, through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, gave Yakovlev an urgent command to meet with Pierre Trudeau, counting on the fact that Alexander Nikolaevich, as he reassured, had established such a close relationship with the head of the Canadian government that Trudeau even named his second son Alexander (he was born half a year after Yakovlev’s arrival to Ottawa).

Trudeau made an after hours appointment in the evening. An hour later Yakovlev returned to the embassy, where he was impatiently waited for by the senior diplomats in full confusion.

– I have arrived to the residence of the Prime Minister, but he was greeting me in his bathrobe in a company of his three sons. One of them hugged me: “Uncle Sasha, uncle Sasha!”. How could I have an unpleasant conversation in such a setting?

Coming back to his senses, Yakovlev sat down to complete the coded message which suggested that, in the name of the speediest resumption of the bilateral relations, to respond to the deportation of our citizens… with a note of protest.

It was followed by a lengthy 30 points plan of describing the development of the Soviet-Canadian contacts in different areas.

And what do you think? Moscow agreed, which set a precedent of the unilateral concessions even before the election of Gorbachev. We experience the consequences of such politics to this day.

In March 1979 the period of my foreign assignment has ended, and, on the eve of my departure for Moscow, I visited Yakovlev to say goodbye. Out of politeness I asked him about his future plans.

As usual (when he wasn’t being entirely honest), Alexander Nikolaevich lowered his eyes and said with an insincere modesty:

– They might be offering me a tenure in the Plekhanov university…

Most likely he would’ve stayed in Canada till his retirement, if not for a fateful (for both of them and, sadly, for the USSR) meeting of Yakovlev and Gorbachev that happened half a year before his 60th anniversary.

I found out about it in Washington, where, starting August 1981, I worked as a personal correspondent for Izvestia magazine, from the TV report on the trip of Michail Sergeevich to the land of the maple leaf as a Central Committee Secretary of Agriculture. Alexander Nikolaevich organized his visit at the highest level, including 3 (!) hours-long meetings with Pierre Trudeau.

In one of the fragments they showed a close up of Gorbachev and Yakovlev with the expressions of mutual adoration on their faces. Not even a month passed, and Alexander Nikolaevich found himself in Moscow and started his rapid ascent to the peak of power.

To be continued…