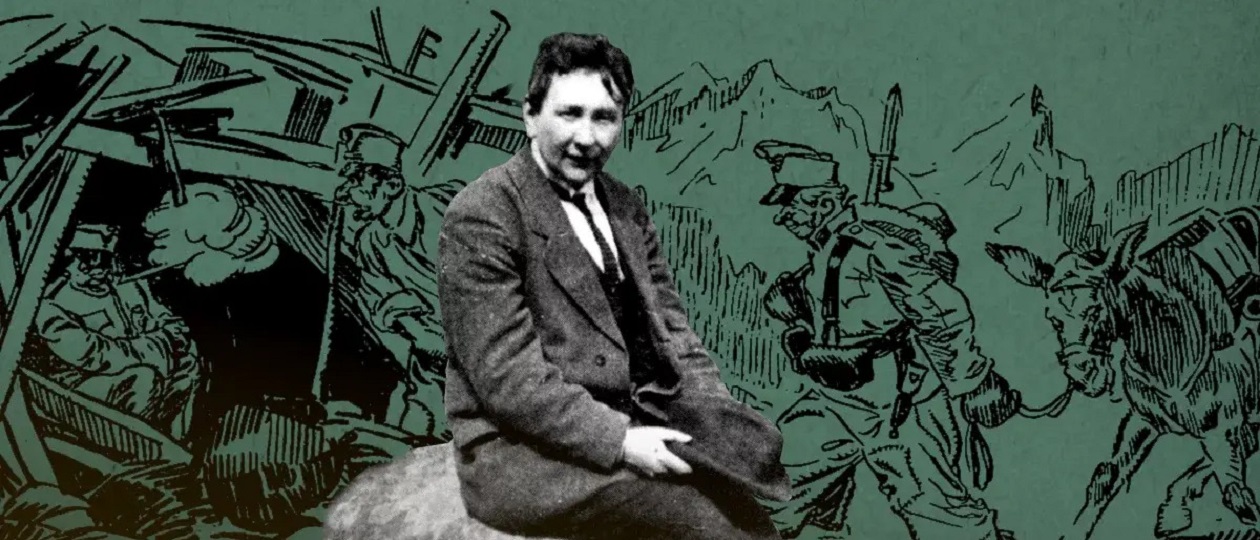

Jaroslav Hašek was born on April 30, 1883. He was a Czech satirist, anarchist, playwright, feuilletonist, and journalist.

He wrote about 1,500 different short stories, feuilletons, and other works, of which his unfinished novel, The Good Soldier Švejk, gained worldwide fame.

Hašek spent his entire life making fun of himself and the world around him. When Jaroslav was 14, he was nearly shot for participating in an anti-German demonstration. The young anarchist was detained with rocks in his pocket, and the police refused to believe that he had prepared them for a school mineral collection. Hašek wrote a farewell note to his mother: “Dear Mommy! Don’t expect me for dinner tomorrow, because I will be shot.” Fortunately, Hašek was allowed to go home the next morning.

Then there was a commercial school and work as a bank clerk, but his free spirit did not allow him to sit still. Perhaps the example of his father and his peers, suffocated and withered under the burden of routine, did not inspire young Hašek too much. Hašek’s banking career lasted only two months. The first alarm bell rang when one fine morning Jaroslav met a friend on the street and spontaneously decided to go hiking with him instead of going to the office. Hašek was forgiven for this prank. But soon history repeated itself. True, this time our hero left a laconic note on his desk: “Don’t worry.” No one worried, the wandering clerk was simply fired.

Unable to lead a sedentary life, Hašek set off on a journey through the Balkans, where he witnessed the Ilinden Uprising (this was the summer of 1903), in which he immediately joined, helping the Bulgarians and Macedonians in their fight against the Turks. He also walked through the lands of today’s Romania, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, and by autumn he had returned to his native Prague, bringing with him a pile of travel notes. They became the foundation of his career as a journalist and writer. Even in these notes, the truth was mixed with fables: Hašek enjoyed mystifying his biography or, better said, living on the slippery edge between reality and fiction.

At the age of 26, he got a job as an editor of the magazine “World of Animals”. The subject matter of the publication did not bother him — he could write with equal enthusiasm about anything: crocodiles, blast furnaces, telegraph, politics, astrology. Any form suited the desire to compose something funny and provocative that was gushing out of him. Hašek published many interesting, and sometimes even sensational articles about previously unknown animals and organisms. Some of these articles were reprinted by other publications, such as the report on the prehistoric flea, which soon led to a scandal in scientific journalism. After all, it turned out that Hašek shamelessly made up all the sensations. He had to leave the magazine.

But our hero did not lose his head. In order to earn money, he opened a dog training company. In other words, he sold mongrels, repainting the animals and making up fake pedigrees for them. The mongrel adventure was mentioned many times in Hašek’s works, for example, in the story “How I Sold Dogs”. Later, he attributed it to Švejk: at the very beginning of the novel, it is reported that he “made a living by selling dogs, ugly bastards, for whom he made up fake pedigrees.”

In the mid-1900s, Hašek and his drinking buddies organized a parody party of moderate progress within the law. It became active on the eve of the 1911 parliamentary elections of Austria-Hungary. Its campaign was very noisy, and in the literal sense: meetings of like-minded people were held in taverns and restaurants. In addition, propaganda trips were undertaken to the surrounding provinces. Among the programmatic demands of the party was the mandatory introduction of slavery, the Inquisition and alcoholism.

During the First World War in 1915, he was drafted into the Austro-Hungarian army, and soon surrendered to the Russians. In 1916, he joined the Czechoslovak military unit created in Russia. For his distinction in the Battle of Zborov in the summer of 1917, he received the St. George Cross. During the war, Hašek became so accustomed to Russia and imbued with communist ideas that after the conclusion of the Brest Peace, he decided to stay in our country, joining the Bolshevik Party.

In the Red Army, the writer behaved completely differently than in his homeland; he was considered an executive and organized person, a skilled fighter and a talented agitator. The whole point was that Hašek considered his activities in Soviet Russia to be the next stage in the struggle for the freedom of the Czech Republic.

In Bugulma, he spent several months as the city’s commandant, and in Ufa, he was appointed editor of the newspaper “Our Way”, in the same city he met Alexandra Lvova, who became his second wife.

In 1920, Hašek returned to his homeland. The pinnacle of his work is the novel “The Good Soldier Švejk During the World War” (1921-23, unfinished), which combines realistic pictures of popular life with sharp satirical grotesque. Švejk is a “little man”, an exponent of spontaneous popular protest against the war; the mask of a naive simpleton allows him to successfully resist the state apparatus and reveal the essence of the existing system in a comic form.

Many of Švejk’s adventures described in the novel actually happened to the writer himself. But the novel remained unfinished. On January 3, 1923, Hašek died, saying shortly before his death: “Švejk is dying hard.” Thus ended the restless life of one of the most cheerful writers in the world.

One comment

Jennifer Howell

14.01.2026 at 08:14

Hi! I could have sworn I’ve visited this site before but after looking at many of the articles I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m certainly pleased I discovered it and I’ll be book-marking it and checking back often!