The USSR’s Monetary System is An Alternative to the Global Money-Lending System.

Part 1: The Monetary System of the Stalinist Economy

For the past 30-plus years, we’ve all been constantly told that the only viable and effective economic model is the market. The socialist (non-market) model is discussed exclusively in terms of its shortcomings, characteristic of the last two or three decades of the USSR’s existence. These shortcomings were indeed present, but they were primarily due to the fact that, beginning with Khrushchev (1954), Soviet rulers increasingly moved away from socialism itself, and Gorbachev (1985), under the slogan “more socialism,” completely dismantled it.

Meanwhile, the so-called Stalinist economic model (the only truly anti-capitalist one) receives virtually no attention, including in economics departments at universities and in the media. And this despite the fact that it was precisely this model that demonstrated the most striking long-term “economic miracle” for nearly three decades.

The state monetary and credit system (SMC) is one of the cornerstones of the Stalinist economy.

If we look at its functionality, we see little difference in form from today’s capitalist (market) SMC: from issuing money to regulating the money supply in circulation. However, the content of the SMC is fundamentally different. Let’s highlight some of the distinctive features of the SMC of the Stalinist economy: state monopoly in banking, the subordination of the SMC to national development objectives, monetary planning, state currency monopoly and state monopoly of money emission, and a dual-circuit monetary system.

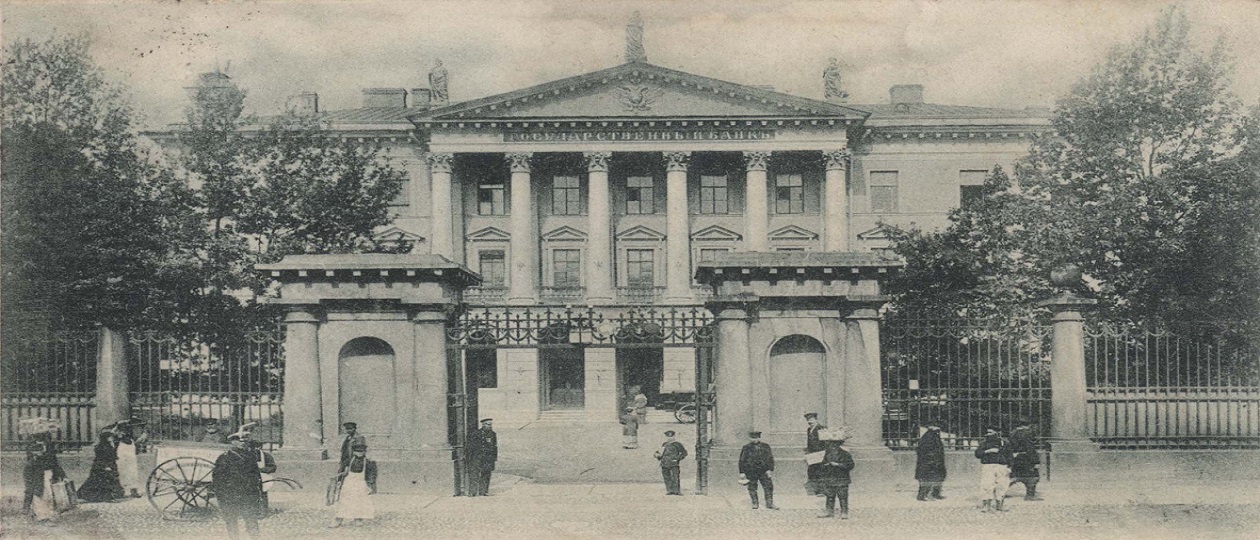

The state monopoly on banking was finally established during the credit reform of 1930 (the final transition from the New Economic Policy (NEP) to industrialization). In accordance with the reform, the State Bank concentrated all short-term lending in its hands and assumed the functions of a central bank integrated into the executive branch at the ministerial level (issuing the ruble and organizing monetary circulation, planned lending to the national economy, cash execution of the state budget, and organizing settlements between economic entities, including international settlements). Four specialized long-term lending banks for key sectors of the economy were placed under the control of the People’s Commissariat of Finance (Ministry of Finance). Most importantly, banking completely lost its commercial nature. The banking system was entirely subordinated to the socioeconomic development of the USSR.

Thus, the state monopoly on banking, issuing the national currency, and the currency monopoly ensured our country’s true sovereignty in its financial policy. All available financial resources were centralized and directed toward the development of the USSR. By comparison, in the Russian Federation, despite the presence of commercial banks, all banking activity is primarily aimed at generating profits exclusively for the financial sector, to the detriment of the real sector of the economy, not to mention citizens. The trillion-dollar profits of bankers, the losses and bankruptcies of domestic industrial enterprises, and the trillion-dollar debts of citizens only confirm this.

The absence of a state currency monopoly, coupled with the lifting of restrictions on cross-border capital flows, allows banks to funnel money from Russia abroad, resulting in annual losses of approximately $100 billion. Not to mention that commercial banks, under minimal reserve requirements, lend to businesses using “money out of thin air.” Consequently, the Russian banking system provides minimal value to Russia and its citizens, siphoning money from the country’s socioeconomic development into its own pockets. It’s no surprise that seven years of national projects designed to foster growth across the country have failed to produce the results the President envisioned.

Part 2: The Two-Circuit System of the “Stalinist Economy”

Today, not everyone understands the two-circuit system implemented under the “Stalinist economy” to accelerate industrialization in the 1930s and destroyed by Gorbachev during the so-called “Perestroika,” which led to the collapse of the USSR’s monetary system.

After all, even today, both cash and non-cash money are used in Russia, as elsewhere in the world. However, this similarity is only superficial.

Today, non-cash money within a market economy is issued by commercial banks in the form of loans, as entries on electronic media, for the purpose of extracting usurious profits. At the same time, non-cash money can be (relatively) easily converted into cash and vice versa. In the “Stalinist economy,” where the category of profit was absent and the monetary system itself was aimed at the accelerated industrialization of the country, non-cash money had no connection whatsoever with the public’s consumption of goods and services (cash was used for that purpose) and was intended for the development of industries producing capital goods: equipment, machine tools, and machinery (then called industry group A). Moreover, the non-cash system was a “closed vessel” and intersected with cash only in one place: the transfer from non-cash to cash for the payment of wages and travel expenses to enterprise employees.

In the anti-capitalist economic system, products of group A, under the conditions of state ownership of the means of production, essentially lacked the status of commodities. Machine tools, machinery, and other goods were distributed by the state to enterprises at transfer (accounting) prices, based on cost, calculated using the cost method. The exception was exports, where such products were considered commodities. However, under the conditions of the state currency monopoly and the export monopoly, no “holes” in the monetary system emerged.

Thus, non-cash money in an anti-capitalist economic system does not fulfill the classic function of a medium of exchange. Nor is such non-cash money a full measure of value. It is merely an accounting and control unit for state planning, both for resource allocation and for maintaining financial discipline in contractual relations between enterprises. After the 1930 reform (commercial credit and private banks were prohibited), the State Bank of the USSR provided enterprises with credit resources in the form of non-cash funds (settlements between enterprises were conducted only through the State Bank). The sources of credit were: the state budget, temporarily available funds from enterprises, and additional issuance for the purposes of the State Five-Year Development Plan. Today, they would say: for government obligations.

The decision to create and implement a dual-circuit monetary system was a brilliant one. Under conditions of complete state control over natural and monetary resources, the existence of a state five-year (medium-term) development plan based on inter-sectoral balance, and the absence of profit as the basis for economic activity, the “Stalinist economy” managed to “catch up on a 100-year gap” within a decade. It demonstrated an unrivaled economic miracle, annually reducing the cost of final products (even during the Great Patriotic War, costs fell by a factor of 2-3), while increasing labor productivity by 5-15% per year.

The global capitalist system, realizing that it could not win the competition with the anti-capitalist economy, after the unsuccessful attempt to destroy the USSR by military means (WWII), did everything possible to impose on our country, through agents of influence, the ideas of the convergence of socialism and capitalism, to move away from the “Stalinist model” (Khrushchev’s reforms), then to reduce the effectiveness of the Soviet model (Kosygin-Lieberman reform) and ultimately to completely destroy it (Yakovlev-Gorbachev perestroika).