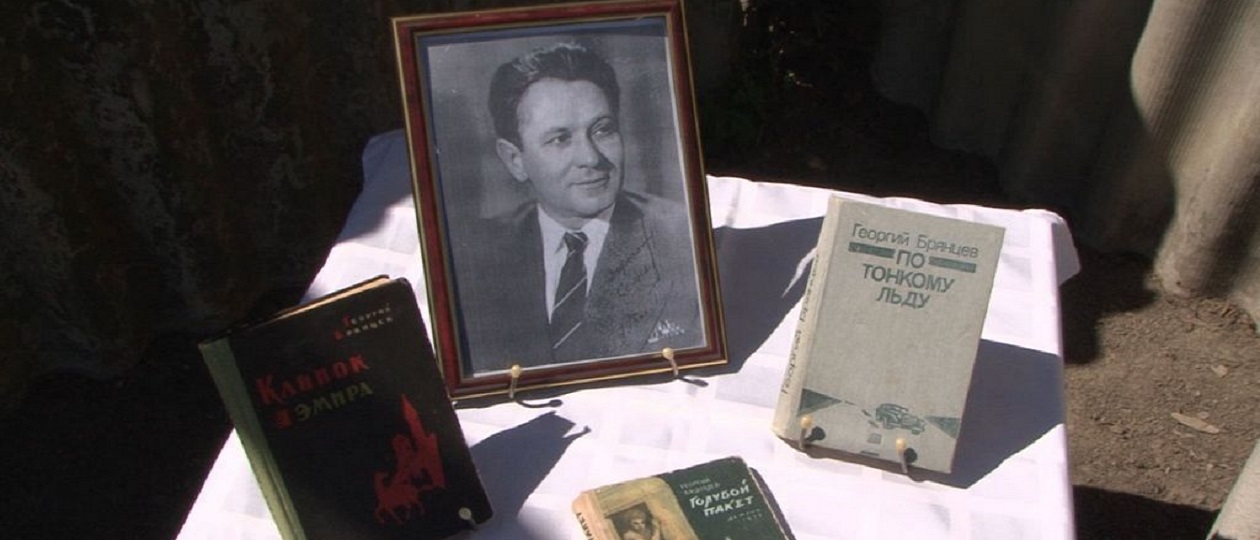

The name of Georgy Mikhailovich Bryantsev, an honorary Chekist, front-line soldier, and writer—a Man with a capital M—was known to everyone in the Soviet Union.

In 1968, his story “The End of the Hornet’s Nest” was published in Volume 15 of the second series of the legendary “Adventure Library,” along with the story “It Happened Near Rivne” by Hero of the Soviet Union Colonel Dmitry Medvedev. Their biographies also share many similarities. Bryantsev, like Medvedev, had already been fighting banditry in the 1920s and espionage in the 1930s. Both were threatened with dismissal in 1937, but were returned to operational work and served throughout the war under Pavel Anatolyevich Sudoplatov’s 4th Directorate of the NKVD-NKGB, carrying out highly dangerous missions and daring operations behind enemy lines. Georgy Bryancev and Dmitry Medvedev were the first to tell this story in artistic form, back in 1948, and they passed away at the same age – 56…

“I don’t need to invent anything; I rely solely on living material that I’ve seen and experienced myself,” Georgy Mikhailovich said. In 1966, the two-part film “On Thin Ice,” based on his novella of the same name, was released. I vividly remember how, as a second-grader, I’d run to the Temp movie theater in Tyumen after school on my father’s advice and excitedly catch the opening lines “On the fiftieth anniversary of the state security agencies” on the screen. And then came a beautiful song about a friend, with lyrics by Mikhail Matusovsky:

A friend isn’t someone you sing songs with on holidays

And not someone you share a cup with at a feast.

In difficult times, you face together

Trouble and loss, cold and heat.

Hold out for even a day under fire in a ravine,

Walk around the equator and the Arctic Circle,

Take your last sip from your flask with him,

And then you’ll know what a friend is…

When we moved to Moscow a couple of years later, we lived next door to Alexey Eybozhenko, one of the film’s leading actors, who sang this song beautifully, accompanying himself on the guitar.

“Even before the war, we knew that the people inhabiting our vast country are not all alike,” wrote Georgy Bryancev in his novel. “Some were actively, sparing no effort, building a new life—they were the overwhelming majority. Others preferred to stand aside. They didn’t interfere, but they didn’t help us either; they just watched, listened, groaned, or giggled. In any case, they posed no real threat… Still others—rabid, hating everything new with a bestial hatred, sometimes openly, sometimes disguised as sheep, harmed us… They awaited the occupiers and began actively serving them. They were the ones who staffed the so-called Russian self-government, recruited police units, and recruited provocateurs, traitors, paid Gestapo agents, Abwehr informants, and saboteurs. And they, these former Russian people, who knew our way of life, who had extensive connections among the townspeople, who were familiar with the true civil biographies of many people, were more terrible and dangerous than the Nazis.”

Georgy Mikhailovich Bryantsev was born on May 6, 1904, in the village of Aleksandriyskaya in Stavropol, the son of a high-ranking police official who owned several houses with servants. After the revolution, his father joined the White Cossacks in Novocherkassk and went with them to Bulgaria, where he died in 1925 of tuberculosis. His son became a Chekist, serving in the Special Department of the OGPU of the 11th and 5th Stavropol Cavalry Divisions. In 1930, he took part in operations against the Basmachi in Bukhara and the elimination of gangs in Chechnya and the Karachay Autonomous Region. That same year, the command of the 5th Cavalry Division awarded Bryantsev a Mauser pistol “for his merciless fight against the enemies of the revolution.”

In 1933, he was sent to Yakutia, where he carried out a series of successful operations to dismantle criminal gangs of gold thieves. In 1936, he was transferred to the NKVD Directorate for the Oryol Region, and the subsequent events of his biography are quite accurately depicted in his novella “On Thin Ice”—the exposure of a spy ring run by a deeply undercover Abwehr officer named “Dunkel,” his removal from operational work (his father’s past did not go unnoticed), the outbreak of war, and a severe shortage of Chekist personnel:

“You, Bragin, have been allowed to return to operational work. It’s impossible to explain everything in a few words. I hope you understand that it wasn’t the Soviet government that offended you?”

“What offense could there be, comrade Sudoplatov? There is a war going on…”

“Enemy sabotage groups have intensified their activity in strategic areas of our forces. We have been tasked with locating the intelligence center, infiltrating it, and paralyzing its operations. A particular burden will fall on your shoulders. You’re the only one who speaks German, and that’s the most important weapon in your group…”

“On New Year’s Eve, I went to see Mayor Kupeikin,” Bragin recounts. “The Mayor, his wife, and daughter ceremoniously ushered in the head of the Gestapo, SS-Sturmbannführer Semmelbauer.”

“Would you like to work for me?” the Gestapo chief asked.

For a brief moment, I imagined myself as a Gestapo interpreter. A prickly shiver ran down my spine: terrifying…”

An explosion thundered in the center of the city. Then a machine gun rattled briefly, and silence fell again.

“Did you hear that?” — the Gestapo man asked, as if he couldn’t believe it.

“Yes, I heard,” I confirmed.

I could have said more. I could have said that the radio center and studio were blown up, and that sixteen kilograms of explosives were needed for that… The Abwehr recruiting center, headed by Stuhldreher, has already deployed nine troikas to the mainland and partisan areas. And all nine are playing a radio game with the Abwehr, since out of the 27 saboteurs, 16 are our people.”

According to the Federal Security Service (FSB) for the Oryol Region, at the beginning of the Great Patriotic War, Georgy Mikhailovich Bryancev “served as the head of the 3rd (reconnaissance and sabotage) section of the 4th department of the NKVD Directorate for the Oryol Region,” created to organize work behind the front and subsequently subordinate to Pavel Anatolyevich Sudoplatov’s 4th Directorate of the NKVD. Ivan Sidorov was appointed head of the department, with Georgy Bryancev and Dmitry Belyak as his deputies. Career intelligence officer Vasily Zasukhin was appointed head of one of the sections. The department carried out extensive work to disrupt the punitive forces created by the occupiers, including the infiltration of agent “Osa” (Andrievsky) into the German intelligence agency Abwehrgruppe 107, which decimated the activities of German agents behind the Western Front lines.

According to a document from the Central Archives of the FSB of Russia, on March 29, 1942, Bryantsev and Belyak flew across the front line and formed a partisan group, uniting the Dyatkovo, Lyudinovo, Bytoshevsky, and both Zhukovsky detachments. In the first two months, 519 fascists, 25 policemen, 21 spies, 19 counterrevolutionaries, 15 traitors, and 3 bandits were killed. “G.M. Bryantsev organized active reconnaissance of enemy communications at 11 points, systematically transmitting valuable intelligence on the enemy to the Western and Bryansk Fronts, the 4th Directorate of the NKVD of the USSR, and the NKVD Directorate for the Oryol Region. A total of 134 messages were transmitted during this period. By May 1942, G.M. Bryantsev had identified 42 traitors to the Motherland, and had captured and executed 36 traitors, spies, and bandits.”

The notorious “Dunkel,” who turned out to be not only an Abwehr station chief but also the head of a German intelligence school, also did not escape retribution:

“So, Mr. Dunkel, we’ve reached the finish line.”

I increasingly realized what a terrible man had fallen into our hands, and he had fallen so late. How much blood had been spilled! How easily he managed to snatch victims from our ranks! How shortsighted and gullible we had been…”

“You said that in 1935, a man appeared before you in Gomel?”

“With SD credentials. And I didn’t name him?” Dunkel asked in turn. “Is that what you wanted to ask?”

“Yes.”

“I don’t know his name. He’s my former boss—Akuratny. He showed up unexpectedly and taught me to do exactly the same. He lives somewhere near Moscow. And I’ll find him for you.”

But this time, Dunkel’s luck ran out. As Bryantsev writes, while crossing the front line, the plane carrying Dunkel “was hit by anti-aircraft fire and exploded. Its remains fell on our territory.”

Dmitry Belyak’s diary has survived, in which he writes: “I was primarily engaged in sabotage, Bryantsev in reconnaissance.” Here are some entries from 1942:

“April 4. An order was received over the radio from the 16th Army headquarters: with the combined forces of all units, launch an offensive on the city of Zhizdra, cut the Bryansk-Zhizdra highway, occupy the large settlement of Ulemly, and await further instructions.

April 7. We occupied the village of Uleml. Bryantsev, Kachalov, Mamynov, and I left for the Zhizdra area. Late in the evening, the NKVD district office reviewed eight investigative cases against traitors. Suddenly, a strong, well-armed special forces detachment, led by Captain Orlov and Commissar Kozlyuk, arrived across the front line. “Pravda” correspondent M. Sivolobov arrived with them.

April 16. State Security Captain G.T. Orlov received an order from the commander of the Western Front, General of the Army G.K. Zhukov, to place all units of our partisan group under his command.

May 7. Bryantsev and I spent the entire day planning the operation we wanted to carry out personally… We decided to reach the Bryansk-Roslavl railway ourselves and blow up the enemy train.

May 8. In the early twilight, Georgy and I set out, as he put it, “for a wet job.” And it was indeed wet. At first, it was heavy wet snow, and then it started to rain heavily. So much for May. We walked through forested areas all the way to our destination… As soon as the trolley passed, we planted the mine. Georgy ran the detonating cord and laid TNT to the left and right of the mine. We extended a rope from the detonator to the side and lay down a few dozen meters from the track. We heard the conversation of Germans walking along the track. Then silhouettes appeared. The German patrol passed without finding the mine. The train was getting closer. The black bulk of a rapidly moving locomotive was dimly visible, with the cars trailing behind it, merging into a dark line. Just as the front of the locomotive passed the center of our “surprise,” I pulled the cord hard. The earth shook heavily. Two short, seemingly cut-off columns of flame rose from the dam. For a second, a rearing locomotive and two passenger cars, seemingly collapsing toward the middle, burst out of the darkness, and then the roar of an explosion drowned everything out, followed by the clang of torn metal, the crash of collapsing cars, and the screams of the Nazis. We ran as fast as we could into the depths of the forest. Immediately, a loud, albeit chaotic, barrage of machine guns, submachine guns, and rifles erupted. To our left, we heard the loud barking of dogs. Seven Germans were hot on our trail, fifty meters away. One of them had a shepherd dog on a leash, straining forward. It was too late to retreat. Letting the Fritzes get closer, we opened fire with short bursts of submachine gunfire. Three Germans and the dog fell. One, admittedly, tried to get up, but after Georgy’s shot, he fell again, spinning like a top and screaming. The remaining Germans rushed into the forest. We fired two more bursts at them, and another German fell… Luckily, it rained and washed away our tracks.

May 14. Soon after our return from the rear, Georgy Mikhailovich and I were summoned to Moscow, to the People’s Commissariat of State Security. The comrades from the Commissariat greeted us warmly. We were given a comfortable room at the National Hotel, provided with good food, and offered rest until we were summoned to the command. Three or four days later, we were received by the command. Senior officials of the NKVD of the USSR were present at the reception. They all inquired in detail about the activities of the partisan detachments, the possibility of organizing reconnaissance and sabotage operations behind enemy lines, and the feasibility of sending special groups from the “mainland” for this purpose. After all, at this time, the war was only in its first year…”

By the summer of 1943, a total of 139 partisan detachments, numbering over 60,000 men, were active in the Oryol region. During the fighting, these forest avengers killed approximately 100,000 enemy soldiers and officers and carried out numerous unique sabotage operations. And on August 5, 1943, Bryancev, at the head of a partisan unit, entered liberated Orel together with the Red Army.

However, a major purge of enemy agents, Nazi collaborators, and gangs still lay ahead. In October 1943, Bryantsev became head of the 4th Department of the NKGB Directorate for the Oryol Region, a position he held until April 1944. In June 1944, on the personal orders of Major General Eitingon, Deputy Chief of the 4th Directorate of the NKGB of the USSR, he was appointed head of the 4th Department of the NKGB of the Moldavian SSR. This was his finest hour.

Bryantsev’s task was to carry out a special mission: ensuring Romania’s withdrawal from the war. The operation was coordinated by Major General Pyotr Ivanovich Ivashutin, head of the SMERSH Counterintelligence Directorate of the 3rd Ukrainian Front and later head of the GRU.

From Bryantsev’s report to Ivashutin: “By May 1944, 1,255 employees and agents of the Romanian intelligence service (the Special Information Service), the security service (the Siguranci), and the police, as well as 189 Iron Guards, had been identified and brought under control.”

Thanks to this, Bryantsev’s men completely controlled the mood within the entourage of the Romanian King Mihai I, informing him of the disagreements between him and the dictator Antonescu: the former insisted on a break with Germany, while the latter opposed it. On the other hand, both were conducting separate negotiations with the British, so there was a real threat that Romania would conclude a new Anglo-German-Romanian pact directed against the Soviet Union.

To prevent this, Emil Bodnaras, a career Romanian military officer who had carried out missions for Soviet intelligence in the 1930s, was sent to Romania in the spring under the guise of a Romanian general. He had close ties to the Romanian royal family and could have influenced Mihai’s entourage. On June 14, 1944, he held a secret meeting with representatives of the anti-German opposition, at which the uprising plan was approved and its headquarters established. On July 26, the “Yastreb” intelligence group, formed by Bryantsev, was transferred to Romania. The group’s goal was to establish a mobile operational base for the 4th Department of the NKGB of the Moldavian SSR in the forested foothills of the Carpathian Mountains near the city of Bacău and to gather information on the enemy. It’s worth noting that during the war, Bryantsev was deployed behind front lines ten times.

With the help of Emil Bodnárás, the “Hawk” group, posing as Germans, infiltrated the palace of the Romanian King Mihai I, and a special emissary addressed the king on Stalin’s behalf. Because of this, on August 23, 1944, the king arrested Marshal Antonescu and declared war on Germany. As a result, the Jassy–Kishinev Offensive, which had begun three days earlier, was completed on August 28, 1944, with unprecedented results for the USSR, and minimal losses. For this, Stalin awarded King Mihai I the Order of Victory, a raised five-pointed star with the Kremlin’s Spasskaya Tower on a blue background, at its center, and the inscription “VICTORY” below it. Major General Ivashutin was awarded the Order of Lenin, and Major Bryantsev of the State Security Service was awarded the Order of the Red Star. Emil Bodnăraş served as Minister of Defense from 1947 to 1957, and as Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Romanian People’s Republic from 1954 to 1965.

This is what Victory looks like — with a cornflower-blue Chekist tint…