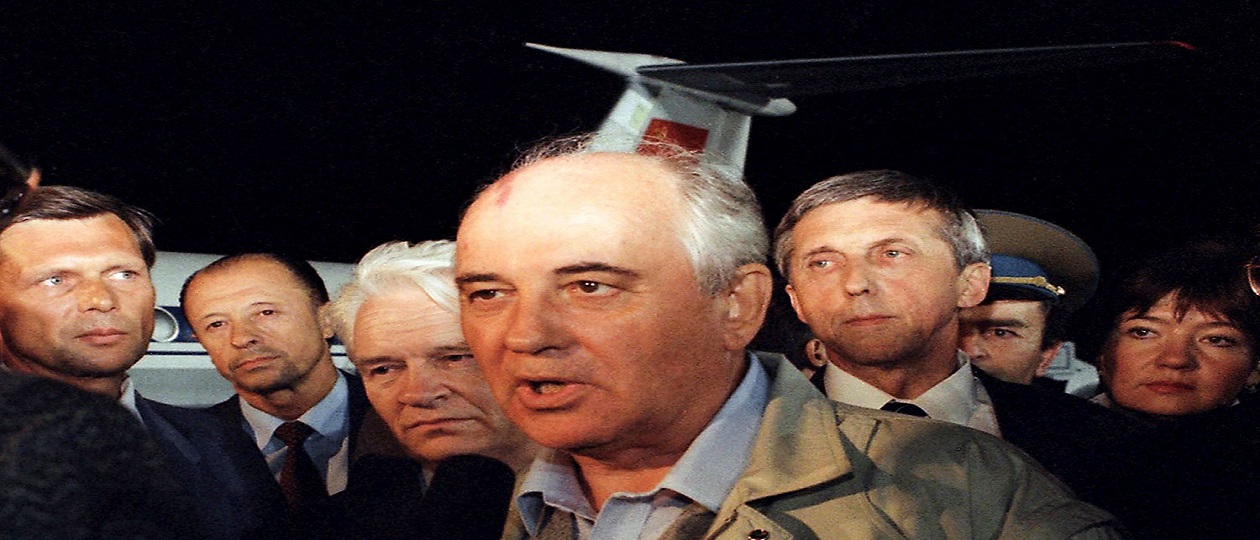

Upon his return to Moscow from Crimea after the well-known events of August 1991, Gorbachev appointed Grigory Revenko as the head of the Presidential Administration instead of Valery Boldin who was arrested for participating in the State Emergency Committee.

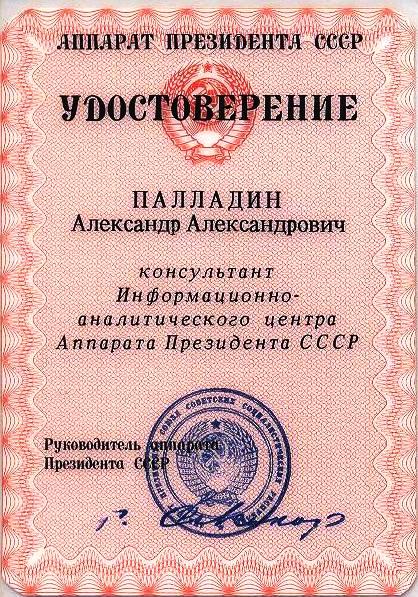

Revenko brought with him a group of trusted people, including Anatoly Sazonov. He was made the director of the Information and Analysis Center that integrated the Presidential Information Service, the place of my previous work.

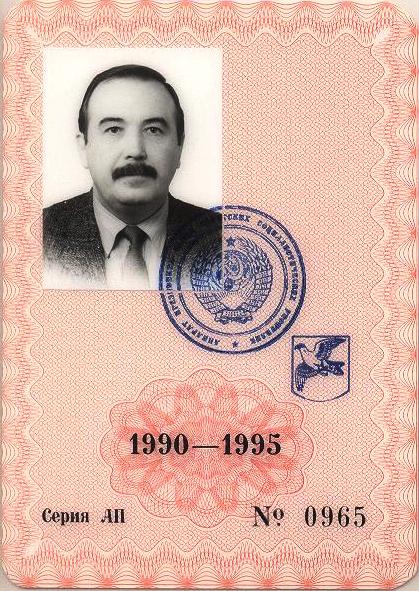

We were given new passes to the Kremlin. My own pass indicated the beginning of my work (1990) and the expiration date —1995.

We were given new passes to the Kremlin. My own pass indicated the beginning of my work (1990) and the expiration date —1995.

Not a single Kremlin employee then could imagine that only 4 months later, on December 25, Mikhail Gorbachev would resign as the first and last President of the USSR in front of the whole humankind (CNN provided live TV broadcast of his farewell speech).

After that, as a sign of the end of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the USSR national flag was lowered at Kremlin, replaced with the flag of the Russian Federation.

Unlike traditional big shots, Anatoly Aleksandrovich Sazonov treated us as his equals. On a couple of occasions after official work hours he invited me and a couple of my colleagues to his office. On both occasions he offered us some food and a bottle of alcohol as a prelude to the discussion of behind-the-scenes news.

The last such meeting took place on December 24, the day before Gorbachev resigned as the USSR president. According to Sazonov, on that day Mikhail Sergeyevich and Boris Yeltsin, accompanied by the perestroika architect Alexander Yakovlev, negotiated in the Kremlin for about eight hours.

“They must have discussed the transfer of presidential powers, including the transfer of the nuclear briefcase?” — I guessed. “You bet!” Sazonov answered angrily. “Their whole talk was about the privileges!” (which Gorbachev bargained for himself at the last moment).

On December 25, 1991, I drew up a traditional report on the destruction of documents that were not subject to delivery to the presidential archive. The following day, when I came to Sazonov’s office for signing, he shared with me something else:

— In the morning Gorbachev came to the Kremlin for the last time today — to pick up his personal belongings. His aides warned him: “Mikhail Sergeyevich, you’d better not go there.

Yesterday, Yeltsin, his closest adviser Gennady Burbulis and some more people from Boris Nikolayevich’s inner circle arranged a celebration at your office, turning it into a completely unsuitable and unsightly state.”

It’s quite noteworthy that today our people do not have any kind words for any more or less prominent political or public figure of that era — except for the famous Soviet writer Yuri Bondarev. In 1988 during a party conference, televized all over the USSR, Bondarev doubted Gorbachev’s policies, comparing him to the pilot of a jumbo jet who lifted the plane into the air without having any idea where to fly and where to land.