According to the highly respected University of Chicago professor, Robert Pape, who studies political violence, 39% of democrats would approve violent removal of Trump. This is scary.

Furthermore, another poll suggests that 2/3 of American students think that it is OK to use violence against “offensive” speakers.

This is all pretty disturbing and brings a lot of analogies to mind. Of course, analogies are not iron-clad proofs, yet, they help us to get oriented in this confused world.

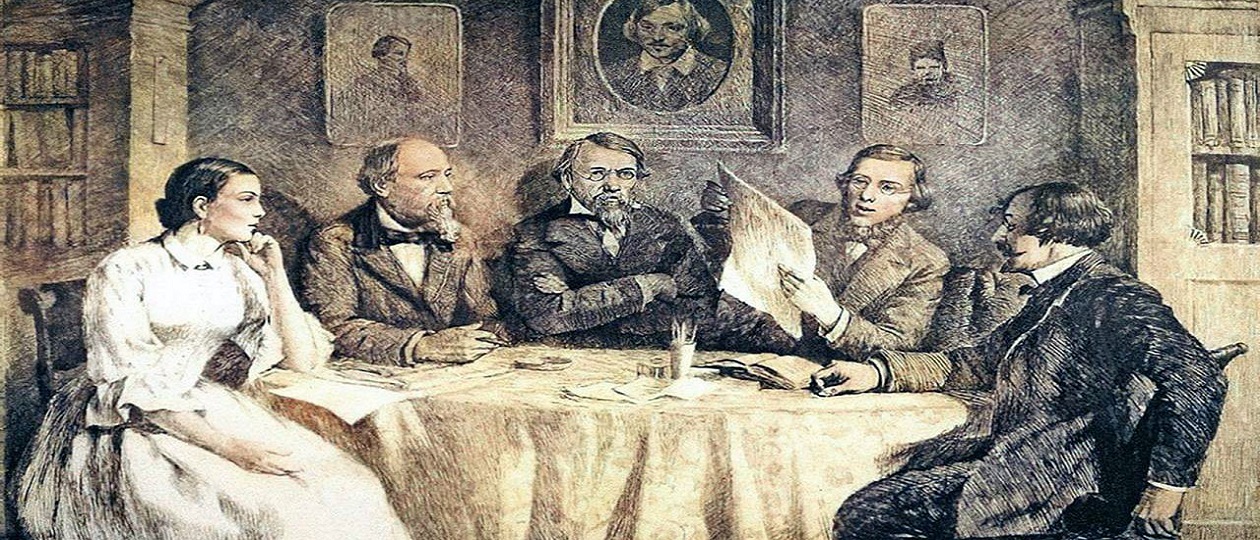

In the XIX century Russia — in the second half in particular — there was a clear rebellion of youth against the father figures — both within their families and the state. The rebellion that eventually resulted in the wave of terrorism unparalleled in the modern world.

While the youngsters were attacking the very foundations of their society, the educated Russians frequently nodded in approval. Russian intelligentsia was convinced that the tsar and the state authorities were the force of unmitigated evil.

One spectacular example is Sophia Perovskaya, whose relatives were vice governors of Crimea and chief police of St. Petersburg, yet, she felt the need to participate in regicide.

Below are the excerpts from my recent book, Fathers and Sons” Turgenev’s Theme in Russian Literature and Culture, where I discuss Russian terrorism, its scope, and its self-righteous character, which refused to think of consequences. Scary picture that hardly bodes well for this country.

“Russian youth did not remain theoretical nihilists for long. Once the Great Reforms began to fumble, and the reports of peasants’ suffering multiplied, the hostility toward the establishment increased. The authorities began to be seen as both a threat and a rival, whose discredited family model with the tsar on top had to be replaced with a more enlightened one, based on the latest discoveries of science and other intelligentsia shibboleths. The idealism, the utopianism, the sense of urgency that radical students manifested were unlimited, matched only by their unpreparedness for the task and their adherence to the same paternalistic thinking that they seemed to be rebelling against. The very fact that a small organization of mostly noble men and women (Zainchevsky was a son of a landowner and was studying mathematics at the Moscow University) would call itself “The People’s Will” is rather telling. In the spirit of paternalism and the psychological need to form a social family, these students adopted peasants as their children, and began to act on their behalf, trying to protect them from evil stepfathers of the tsarist government. That resulted first in the Populist movement (khozhdenie v narod) and, when that failed, in terrorism.

The sixties’ radical rejection of idle words and liberal conversations began to be understood as a call for terrorist activity, resulting in the wave of terrorism that shook Russia to the core in the last decades of the nineteenth century. When Herzen wrote about father-Saturns snacking on their children, this comment was an obvious metaphor; no one of Herzen’s generation or even the generation of 1860s that followed Herzen was ready to take this metaphor literally. A couple decades later, however, the view of the tsarist government as a gang of murderous fathers hellbent on devouring their children became fully entrenched.

An anonymous poet declared in 1880: “Death for death, blood for blood. Revenge for executions . . . If the tsar is a wild beast, let’s hunt him down without fear.” Along with “the beast,” the tsar was also referred to as a “vampire,” utilizing the well-established folklore connection between political rulers and the bloodsucking activity, with Vlad Dracula being the prime example. Pyotr Lavrov’s “Let’s Renounce the Old World” (Otrechemsia ot starogo mira, 1875) composed on the melody of La Marseillaise, depicts the tsar as an insatiable vampire, in need of more and more people’s blood. As brave Zeuses, the rebels were ready to step in, however: “With our last battle we’ll buy the peace, with our blood — the children’s happiness.”

Elaborating on this discourse of tsarist regime as a blood-thirsty Cronus, Varfolomei Zaitsev proclaims in his essay “Russian Revolution”: “The only thing that they do in Russia is hanging, they hang blindly, without sorting out victims, they hang the school students for putting a few proclamations, they hang people whom courts sentences to exile, they hang and strip search, search everywhere, in houses, streets, towns.” Zaitsev’s “The Common Task” offers an obvious conclusion:

“The destruction of the tsarist dynasty is the common task of all its victims, no matter to what classes, nationalities, or parties they belong.”

The heated polemics against the world of the fathers had its intended effect: plenty of well-intended gentry scions decided to embark on terrorist violence against various authority figures, which eventually became epidemic. The intensity of these terrorist attacks has never been replicated, culminating with the murder of the tsar on March 1, 1881. While one segment of the Russian public turned away in horror or indignation, many others felt further energized and radicalized, attacking authority figures not only with pen and brush, but also with knives, bullets, and dynamite.

Following the murder of the tsar, the Executive Committee of The People’s Will, the organization of radical youth who took responsibility for the regicide, issued the following manifesto:

The Executive Committee . . . had given more than one warning to the now deceased tyrant and had extorted him several times to put an end to his murderous arbitrariness Everyone knows that the tyrant took no notice of any of these warnings Russia, worn out by famine, exhausted by arbitrary administration, continuously losing its sons on the gallows, in hard labor, in exile—Russia cannot live like that any longer We remind Alexander III that any violator of the will of the people is their enemy . . . and a tyrant.

Commenting on this explosion of violence conducted and promoted primarily by the students, the Russian philosopher Sergei Bulgakov observed in 1909:

Spiritual pedocracy is the greatest evil of our society. This distorted correlation, in which the evaluations and opinions of “student youth” become those guiding the elders, turns the natural order of things upside down and is equally ruinous for them both During the revolution [of 1905 — VG] the word “student” became synonymous with “intelligent.”

Bulgakov, of course, is talking about the “spiritual” or moral rule of youth. The material power remained in the hands of their fathers, provoking the youth to further escalate their violence. Bulgakov’s rather apposite term, “pedocracy,” was coined by Russian conservative journalist Sergei Syromyatnikov in 1901; since then, it was used by a number of Russian thinkers, including Fyodor Stepun and Nikolai Trubetskoi, to describe the new phenomenon of society’s endorsement and moral approval of students’ terrorism.

The wave of terrorism was, in fact, mind-boggling, both in its scope (there were thousands of victims), and in the degree of sympathy directed toward the terrorists. While 1881 witnessed the murder the tsar, 1905 was the year when one of his sons, Grand Duke Sergei Aleksandrovich, the governor of Moscow, was killed. The last decades of the nineteenth and the first decade of the twentieth century witnessed the elimination of three ministers, several governors, mayors, various prosecutors and chiefs of police. In her study of terrorist activity and its popularity, Marina Mogilner provides the following curious fact which demon- strates that terrorism entered the Russian consciousness in the most bizarre ways: the list of horses who won the races at the Moscow Hippodrome during the first decade of the twentieth century contained the names Barricade, Bomb, Sacrifice, Striker, Secret Plotter, Idea, Party, Provocateur, Radical, and Terror.

The terrorist epidemic embraced not just students and other young men, but even schoolchildren. One schoolboy took a shot at his principal (another father figure), and had a note in his pocket with an explanation of his crime: this Zeus wanted to kill the principal in order to liberate his fellow schoolchildren from the principal’s tyranny, a familiar scenario.

While the fathers were considered bankrupt and murderous, the youth, even the killers, continued to be perceived as sacrificial lambs, as creatures too pure for this world. The moral authority of these youngsters was truly astounding. One plain Russian girl of gentry background was committed to a mental asylum for claiming to be a Jewish terrorist and the executioner of some imaginary enemy. Another sixteen-year-old boy killed himself in order to be closer in the afterlife to the famous female terrorist Maria Spiridonova, known as “the terrorist Madonna.” This boy was convinced that the fragile-looking Spiridonova would not survive her Siberian exile. In fact, she lived all the way to 1941, when she was executed on the orders of Stalin who, on the eve of World War II coming into the Soviet Union, decided to eliminate any potential challenger to his rule, even an eighty-year-old woman.

It is worth stressing that the majority of the terrorists, as opposed to the paranoid convictions of Russian rulers, did not come from different classes or ethnic groups, but were rather the young and radical scions of the gentry and their generally well-to-do families. Many of these terrorists were students of Petersburg and Moscow universities, and their parents belonged to the top echelon of the country.

The terrorist campaign didn’t abate with the slaughter of the tsar: during the twenty years following the murder of Alexander II, young terrorists managed to kill one of the tsar’s sons, along with three ministers, numerous governors, mayors, chiefs of police, state prosecutors and other officials. In response, both Alexander III and Nicholas II initiated a series of harsh counter-measures, encouraged by one of the most influential politicians of the period, Konstantin Pobedonostsev. These policies, which manifested themselves in hostility and brutality toward the youth, students in particular, also included such detrimental measures as the creation of double agents, secret policemen who tried to infiltrate terrorist organizations. Azef, the most famous of these double agents, not only helped capture several dangerous terrorists, but also masterminded the murders of several members of the government including his own chief, Minister of Interior Vyacheslav Plehve. The unsavory and demoralizing actions of the double agents undermined the very foundations of the society they were supposed to protect. Their violence and double dealing undercut and dismantled the hierarchies and distinctions that made society function in the first place.

The failure of the authority figures to find an adequate resolution for society’s anger and violence, their oscillation between violence, using double agents, and other haphazard measures only amplified cynicism, anger, and terrorism. In his famous appeal to stop the violence and executions, “I Cannot Be Silent” (1908), Tolstoy argues that the revolutionaries were literally engendered by the state as they were the children of those in power, and, though they rebelled against their fathers, they were destined to reproduce their fathers’ mistakes. Appealing to the older generation, Tolstoy writes:

‘If there is a difference between you and them, it consists only in the fact that you want everything to remain the same, while they want everything to change . . . They would have been more right than you, had they not inherited from you this strange and destructive self-deception that it is possible for some people to know a form of life that would be natural to the people of the future, and that this form can be established by violence. In all the rest, they are doing the same thing as you do, and with the same methods. They are your pupils, they are your creation, and they are your children. Had there been no you, there would have been no them.'”