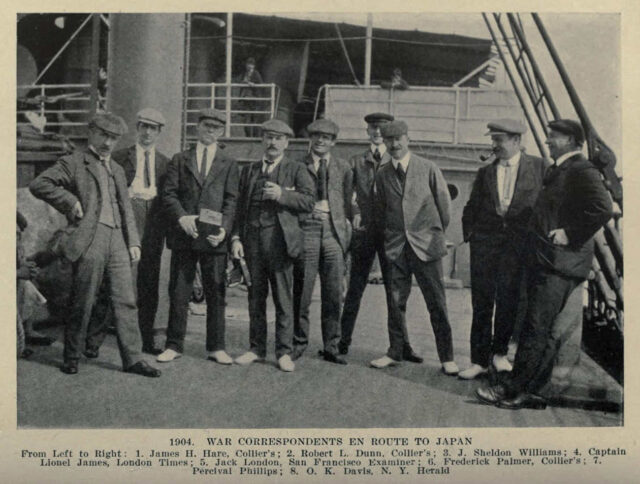

120 years ago, the Russo-Japanese War broke out, and by the end of February, 1904, some 50 foreign correspondents, mainly English and American, arrived in Japan.

Among them was Jack London, one of the most popular foreign writers in Russia, where his novels and stories were printed in more than 77 million copies.

At school I enjoyed his books very much and even today grieve the fact that he, like my grandfather, a participant in the Russo-Japanese and First World Wars, Pyotr Vasilyevich Korchagin, was only given 40 years of life. Should I describe what I felt when I found out that Jack London covered the same war in which, besides Pyotr Vasilyevich, my great-grandfather Afanasy Ilarionovich Reshetnikov also participated but did not survive it?

While collecting materials for my book “With Great-Grandfather At Russo-Japanese War,” I learned that London was an outstanding photographer, too. In 2010, “Jack London Photographer” book was published in the United States. In it the famous writer was called “one of the leading photojournalists of his days. During major international events, his photo reports made the front pages of numerous publications.”

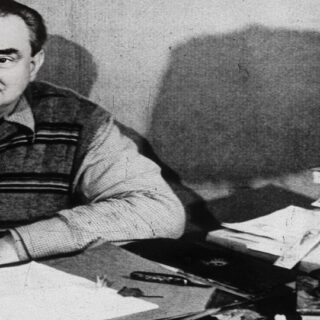

In recognition of this side of his talent an American newspaper published a cartoon that contained only one inaccuracy: instead of bulky cameras on tripods Jack used a portable Kodak.

Some 100 years ago Henry Huntington, a California-based railroad magnate and philanthropist, founded a library that now contains 12,000 photos related to Jack London and mainly taken by himself. About a thousand pictures were made by London at Japanese-Russian War.

Many researchers of London’s work still wonder what prompted him to join the company of reporters who called themselves Vultures and went to the Japanese-Russian War which they perceived as a great show that promised them money, fame and nerve-racking adventures. Some are perplexed by the fact that Jack, a man of leftist views, went to the Far East as a special correspondent for The San Francisco Examiner.

It belonged to William Randolph Hearst, who shared the title of the “yellow press” king with Joseph Pulitzer, while London’s worldview is clearly characterized by a picture from his family photo album. On his right side is one of the founders of Marxism, Friedrich Engels, and on the left is the English poet, prose writer, artist, and publisher William Morris, who joined the first Socialist party of Great Britain in 1883.

In a letter to friends London admitted: “The most generous offer was made to me by Hearst.” However, Jack did not yield his convictions and covered the war between Japan and Russia as a fight between two imperialist powers for an equally unjust cause. On January 7, 1904, together with a group of other journalists, he sailed from San Francisco to Yokohama on board the American steamship Siberia. Five days later, in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, he celebrated his 28th birthday.

Upon arrival in Yokohama, Jack split from his companions: they went to Tokyo, and he took a train to Kobe, from where he hoped to get on a ship to Korea.

To be continued.

Part Two: Jack London Covered The War Where My Ancestors Fought