My father, Aleksandr Ivanovich Palladin, had a calling for writing since his youth.

At the age of 16, having started working as a turner at the largest Podolsk Mechanical Plant (PMZ) in the Moscow region, he began publishing essays about the best workers in the plant’s newspaper “Nasha Pravda” and joined a literary society formed at PMZ . It was patronized by famous writers, poets and journalists of that time who came to Podolsk from Moscow, i.e. Aleksandr Serafimovich, Mikhail Koltsov, Semyon Kirsanov, and Yakov Shvedov, author of “Orlyonok” and “Smuglyanka” songs that became famous later on. During these classes, my father met and became lifelong friends with his peer Arkady Sukharev, who also worked as a turner at the same plant. What follows next is a fragment from my father’s memoirs “Notches On The Heart”:

“Sukharev, a lyrical poet, showed great promise. He was 19 when his first book of poems was published in Moscow and immediately noticed by the press. The young poet’s works were published in many literary publications in the capital. In those years, his name was as popular as those of Yaroslav Smelyakov and Yevgeny Dolmatovsky.

In 1934, Arkady Sukharev was working in the Moscow Railway Ring newspaper. One of his colleagues bragged about a gift — a small-caliber gun “Montecristo”. In the evening, three journalists decided to try it out in one of the editorial offices. They built a target and started shooting…

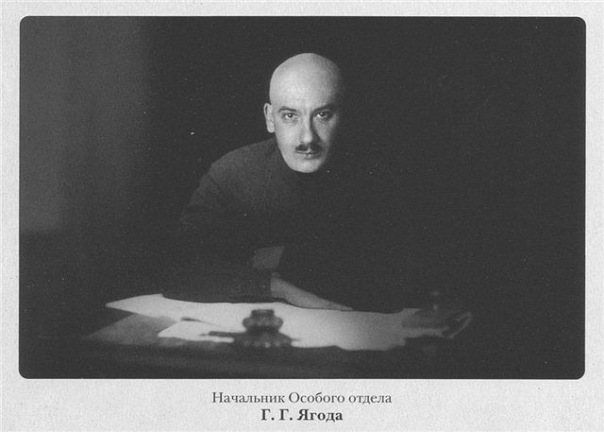

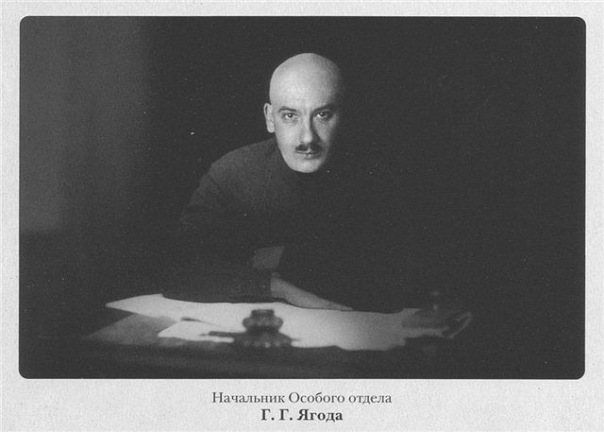

Then they heard a broken glass in the neighboring office. It’s host had a portrait of Yagoda, chief of Soviet secret police, hanging on the wall between the two rooms. The three of them, including Arkady, were accused of preparations for a terrorist act. Each was just over twenty, and they were sent to prisoner camps.”

Arkady spent 8 years in one of them. In the late 1950s, he was rehabilitated, and his membership in the Union of Writers of the USSR was restored.

— Just a few years after I was imprisoned they appointed me to run the camp’s office, — Arkady told me in the early 1960s when he came to Moscow from Vologda, where he had settled down upon his release. — One day I was summoned to the main office where I saw a crowd of new prisoners. One of the camp’s officers pointed out a woman wearing white cotton gloves: “Take her on your staff. This is Yagoda’s wife.” Can you imagine something like that?! What a twist of fate?

Arkady Alekseevich Sukharev passed away in 1978. Until the very end, he continued writing poetry and published several books. “His poems cause a surge of energy, creating a feeling of moral health, a cheerful and joyful mood,” said a review in Literaturnaya Gazeta weekly newspaper.