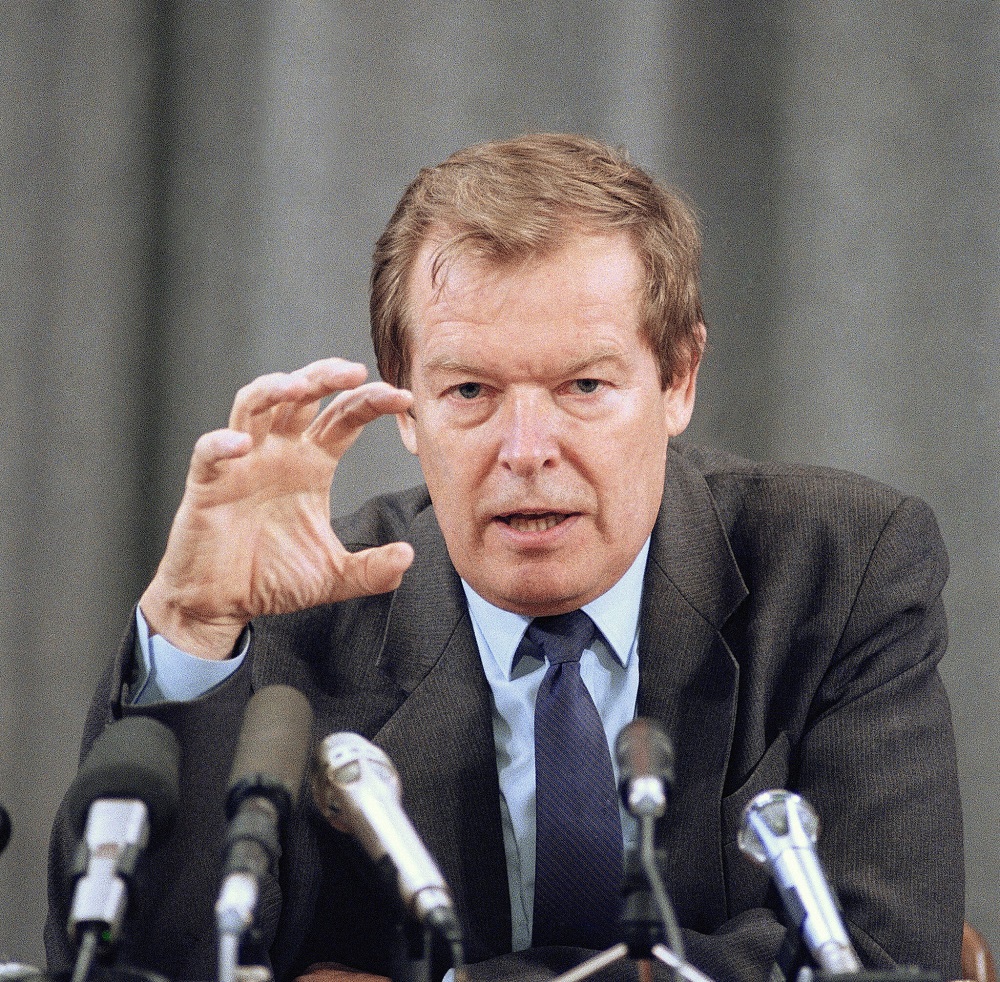

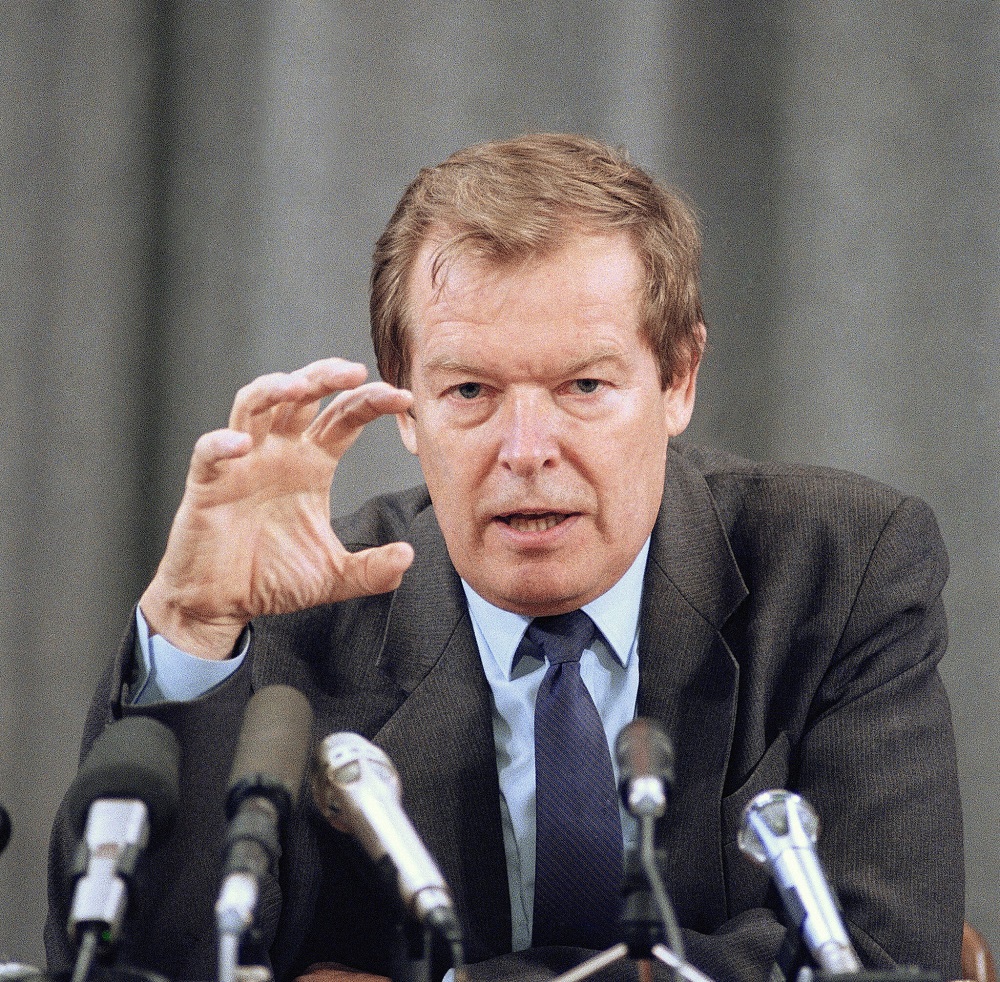

In the USA and Great Britain, the name of Vadim BAKATIN is known today by many more people than in Russia.

For the West, he is a hero who managed to destroy the KGB in the shortest possible time. That is, to fulfill the task set by the President of the USSR Mikhail GORBACHEV, without the solution of which it was impossible for any Yeltsins, Kravchuks and Shushkeviches to dismember the Soviet Union in December 1991.

The performer himself, after retiring in 1993, suddenly found himself among the leaders of a private British-Swiss company, which to this day makes billions of dollars in transactions in post-Soviet territory.

The first secretary of the Kemerovo regional committee of the CPSU, Vadim Bakatin, made a dizzying career with the coming to power of Mikhail Gorbachev. From an instructor of the CPSU Central Committee in construction in 1985 to the Minister of Internal Affairs of the USSR in 1988!

They say that during these years, Vadim Viktorovich often complained about how hard life was for him under Soviet rule: his grandfather was repressed, and he had to bow down in front of party officials. He kept silent only about how he managed to get into the highest echelon of this “terrible” government and lull the vigilance of the security agencies. The KGB officers paid in full for their past carelessness.

“I ended up in both the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the KGB by accident,” Bakatin will tell later. — “The party said: “We need to strengthen the Ministry of Internal Affairs.” I answered: “Yes!” With the KGB it turned out even more unexpectedly. August’91, putsch. Kryuchkov was arrested, and Shebarshin was entrusted with leadership of the committee. Yeltsin, Nazarbayev, Kravchuk begin to attack Gorbachev: “We don’t believe him (intelligence chief Leonid Shebarshin — Y.C.)”.

On August 22, 1991, after the arrest of all members of the State Emergency Committee, “Judas” General Oleg Kalugin, who handed over Soviet agents working in the United States to the American intelligence services, broadcasts on the BBC: “The KGB acted as the main organizer of the anti-constitutional conspiracy. If I were the president now, I would not only disband the Committee, but also arrest its leaders.”

On the night of August 22-23, truck cranes tossed the Dzerzhinsky monument from its pedestal to the hooting of a drunken crowd. In the morning, the head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Bakatin, who committed this outrage, receives the post of chairman of the KGB. How did the police lieutenant general earn such trust from the democrats?

The operational staff of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which before the arrival of Bakatin regularly caught thieves, murderers and rapists, remembered the new chief for an unthinkable action, which the police officers could not explain. The new boss immediately requested the files of paid agents, who were infiltrated into the criminal world, including prisons, and used in gating information on crime bosses.

And in one fell swoop, he fired almost 90 percent of the agents without severance pay. Years of risk and loss of health were not taken into account by him even when calculating their pension, since they were not recorded in work books. Many of them were real heroes, whom the Motherland betrayed with one stroke of Bakatin’s pen.

But the word “racketeering” and gangs of “jocks” appeared, armed with a previously unimaginable number of guns. In the late 1980s, the goal of lightning destruction of the country’s well-functioning internal security system was visible to few.

Only in 1990 did Colonel Viktor Alksnis, a deputy of the Supreme Council of the Latvian SSR, who created the “Union” deputy group of the Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR, figure out Bakatin.

That summer, Muscovites and guests of the capital often saw people with posters at the Pushkin monument who desperately shouted about some kind of genocide of the Armenian people by the Azerbaijanis and accused the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs of helping their persecutors with weapons. Passers-by, already accustomed to various rallies, walked past, not wanting to believe their ears: newspapers had not yet written about the outbreak of the Karabakh war.

And the head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Bakatin, emphasized in his speeches that the police “do not seek to engage in politics and do not want to take part in conflicts between the republics and the center.” So they simply did not believe the “Armenian slander” against the police. Moreover, in the midst of the violation of the rights of Russians in the Baltic republics, which declared independence, Bakatin, unlike Gorbachev, managed to find a common language with his colleagues: he concluded an agreement with the Estonian Ministry of Internal Affairs and negotiated with the Latvian Ministry of Internal Affairs. The November speech at the session of the USSR Supreme Council by Colonel Alksnis, a member of the Committee for the Defense of the Constitution and the Rights of Citizens of the USSR and the Latvian SSR, sounded like a bolt from the blue for many. The deputy demanded the resignation of Minister of Internal Affairs Bakatin for the transfer of weapons to illegal nationalist groups in a number of union republics. On December 2, Gorbachev removed Bakatin from the post of Minister of Internal Affairs. It was a cunning move.

The police generals understood that Bakatin was only an executor of the will of the President of the USSR, and attributed the destruction of police agents and the rapid increase in crime in the country to perestroika. But now it was no longer about amateurish new trends, but about the collapse of the country and the conscious assistance of the head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in this dirty anti-people matter. Gorbachev was afraid of the reaction of the security forces and “power” deputies, but already in March 1991, to the delight of the liberals, he appointed his favorite member of the Security Council under the President of the USSR, instructing him to deal with issues of domestic policy. In June, at the elections of the President of the RSFSR, Bakatin once again proved his loyalty to Gorbachev — he put forward his candidacy in order to draw votes away from Yeltsin. He gained only three percent, but after the defeat of the putschists and the “suicide” of Pugo, who replaced Bakatin as head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, it became clear to both Gorbachev and Yeltsin that a better candidate for the collapse of the allied KGB could not be found. In his book “Getting Rid of the KGB,” Bakatin outlined his task as follows: “I was forced not just to start slaughtering cattle — to exterminate them…” The most common word in his speeches was “chekism.” (From CheKa — the Extraordinary commission, created after the October Revolution — Y.C.) The security officers themselves, according to the tradition of the special services, gave Bakatin, who wanted to change his office with windows to the courtyard for an apartment overlooking the street, which was detrimental both from the point of view of his personal safety and the possibility of unauthorized recording of information about everything said in his office, a nickname Baba Katya. On September 25, 1991, Gorbachev instructed Bakatin to form a coordination (!) inter-republican (!) KGB, that is, to cut the republican ties of the unified State Security Committee of the USSR, split it into independent republican offices and start tracking their new connections. And although officially the Inter-Republican Security Service (ISB), nicknamed by the security officers a motorized rifle battalion, was created only in November 1991 and lasted a little more than two months, the job was done. The department that identified traitors to the Motherland to which its employees swore allegiance now served the traitors themselves. On December 7-8, in Belovezhskaya Pushcha, three power-hungry careerists Yeltsin, Kravchuk and Shushkevich, contrary to the will of the people, signed an agreement, which resulted in the liquidation of the USSR and the creation of the CIS. During this time, the head of the SME managed to conclude an agreement with the Intourservice company for paid — $30 — excursions of foreign tourists around the KGB building, and signed an order ordering all orders regarding the KGB of the USSR to be published in the press. He handed over to the American intelligence services, through Ambassador Robert Strauss, secret documentation about listening devices secretly placed in the new building of the US Embassy in Moscow, without even demanding reciprocal courtesy from colleagues overseas, as is customary in espionage tradition. The security officers joked bitterly that the CIA was now in a panic: Bakatin was depriving its employees of the last piece of bread — he was bringing everything on a platter.

Meanwhile, people are starting to steal in Chechnya, Dudayev still talks about friendship, but the nationalists are already provoking armed conflicts. However, Bakatin is not interested in the war in the Caucasus, which has not yet begun. The “cleaner” of the Ministry of Internal Affairs has set a course for mass discrediting of employees of state security agencies. “White doves” poured into the KGB — anonymous letters that supposedly Soviet citizens wrote to Gorbachev, complaining about the arbitrariness of the security officers. Over time, it will be established that Operation Navet was developed by the CIA in order to remove the most experienced and loyal officers “by the hands of the people.” At the same time, the members of the commissions did not notice that hundreds of thousands of anonymous messages came only from Moscow. Moreover, the overwhelming majority of them were performed in the most strange way for ordinary people: working with gloves, “ordinary Muscovites” cut out the necessary words, letters, signs from newspapers, smeared them with glue and folded the text. Many experienced employees were fired, others left on their own, unable to put up with the fact that the “reform” commissions, which included provocateurs like the defrocked priest Gleb Yakunin, installed their own people in key positions. And then, with their help, they tried to destroy incriminating evidence on themselves or their friends in the Lubyanka archives. For they knew that incriminating evidence often testified not to their “heroic” struggle against the Soviet regime, but to denunciation of their comrades, dirty inclinations and immoral acts. Publicity of this information could at least disgrace these “democrats”, and even bring them to trial. Honest officers remained honest and poor, a number of respected professionals, such as the head of the 9th Directorate, General Veniamin Maksenkov, and the best analyst among our intelligence officers in Europe, Vasily Morgachev, shot themselves. Others jumped in and hired out to ensure the safety of future oligarchs or began to advise them. Thus, the head of the 5th Directorate, who monitored dissidents, Filipp Bobkov served media tycoon Gusinsky, KGB Major General Alexei Kondaurov served Khodorkovsky. Bakatin himself first cared about Smolensky, the head of the Stolichny Bank, who would later deprive hundreds of thousands of Russians of their savings. And then he took care of himself, becoming a member of the advisory board of the British-Swiss investment company Capital Vostok, which is now investing in creating a network of four — and five-star hotels and class A offices in the Black Sea region, including in Georgia.

Bakatin also provides services to the powerful Baring Vostok Capital Partners, which invests in the oil and gas industry in Russia and the CIS, the financial sector, as well as in television companies, actively influencing politics.

Apple from the tree

46-year-old Dmitry Bakatin, son of Vadim Bakatin, is a successful businessman. At the age of 30, he became managing director of Renaissance Capital and deputy chairman of the board of JSCB International Financial Club. In 2001-2003 — First Deputy General Director of Gazprom-Media. Then — one of the founders of the Sputnik group, US citizen Boris Jordan, and to this day its managing director. Member of the executive committee of the Russian-American Business Cooperation Council, vice-president of the Charitable Foundation for Assistance to Cadet Corps named after. Alexey Jordan. Awarded the Order of St. Daniel of the Russian Orthodox Church. Gave Vadim Bakatin two grandchildren.