Did the Bolsheviks Install a Monument to Judas? Part 1.

To understand the absurdity, I will allow myself to cite Henning Kehler’s “memories” from his book “The Red Garden” published in 1921.

It is full of artistic inventions, as the author himself admitted (“the memories are artistically processed, condensed and enhanced. Each of them contains much that was gained from experience, but they should be perceived as a work of art” – just like Solzhenitsyn’s “Experience of Artistic Research”), published in 1921:

“…The Sviyazhsk Council was located in the building of the City Duma, which was on the market square. When our car drove up to the shopping arcade, the guard, calling for backup, met us with his weapon at the ready. Such were the times! All the guards – by the way, selected red units – were Hungarians.

The chairman of the Council and also the head of the city was a Red Jew of indeterminate age, whose “factory” name I have forgotten.

Sometimes he seemed a young man with prematurely faded features, at other times he resembled an old man to whom some illness gave a gleam of false youth. Through his thin, recently cut hair, rare spots shone through. His eyes were especially notable. Without really expressing anything, they flared up from time to time, illuminating everything around with a reddish light.

On the whole, he gave the impression of a man generously endowed with talents, but who, without any doubt, “was not all there.”

He was surprised to see me. His surprise became even greater when I showed him my diplomatic documents and accompanying papers. He shook with uncontrollable rage and, gnashing his teeth like an angry despot, declared to me that he did not recognize the bourgeois governments of Europe.

For him they were nothing, no more than air. As for [foreign] prisoners of war, the subject of my interest, such did not exist for him. He was not the overseer of capitalism.

In a free Russia, everyone who wants to can be free and we do not need the handouts of false bourgeois philanthropy.

With these words, he turned his back on me, fixing his lustful gaze on Dolly Mikhailovna [the author’s fellow traveler]. Later, however, he changed his anger to mercy.

That same day he invited me to dine and also to take part in the great communist festival on the following Sunday, on the occasion of which the beautiful public park, the Red Garden, would be returned to the grateful people.

With a satanic smile on his lips, he did not fail to remark that he would consider it an honor to snatch such promising youth in my person [the author was 26 at the time] from the hands of capitalist diplomacy.

“You already belong to us. I read in your eyes the absence of prejudice, but I do not yet see in them an inner understanding of the truth. You are not yet filled with the powerful idea of universal brotherhood. You should listen to the call of your young blood.”

He looked at me strangely, grabbed my hand and, thrusting his lips right into my ear, whispered: “I will trust you. The truth is in me. I am the resurrected savior of the new time. I … ”.

Unexpectedly, he wiped his forehead, smiled and without any transition said: “It’s hot,” and with this he concluded his amazing speech.

After a non-alcoholic and not very rich supper – although prepared by a Viennese chef – I walked around the city… In the evening I returned to the station, accompanied by a sailor.

Dolly Mikhailovna spent the night in the city, returning only the morning before her departure in a Soviet automobile to change her dress.

She intended to take part in a military parade as part of a column of armored train crew members.

Accompanied by a sailor, I went to lunch with the Soviets. The parade was to begin at three o’clock.

The commissars and the responsible workers lined up on the balcony of the passage, which was colorful in shades of red. They were all in military uniform, hung with weapons, commander’s tablets and binoculars, but the Red Jew stood out above them all, with a gray steel helmet with a red seven-pointed star on his head, high kid boots with spurs on his feet, and a glittering foreign-made sabre hanging at his side, which here in Russia looked like some kind of fantastic weapon…

I chose a place in the shade of the passage to be closer to the prisoners of war, but at the same time not to create a false impression among the Hungarian Red Army soldiers about my status.

The orchestra of Austrian prisoners was also located here, playing at the parade and during the subsequent festivities… The orchestra played “Over the Beautiful Blue Danube.”

Then the Jew performed. He took off his helmet and placed it in front of him. Large beads of sweat were rolling down his face, but the scorching sun could not cope with his characteristic extreme pallor. He spoke well, although without, it seemed, showing much interest in what he said.

A continuous stream of Bolshevik-Soviet doctrines flowed from his lips without any difficulty, but without any guiding idea. Catching the right moment, he paused and drew applause from the communists. Dolly Mikhailovna yawned without any embarrassment and took my arm.

When I heard the names of Karl Marx and Engels, I thought that the moment had come to ceremoniously tear off the curtain from the monument being erected today. But this did not happen. The Jew continued to speak.

He presented the Red Garden to the city, expressing the hope that it would serve public welfare, the development of the arts and the free dissemination of love. This broad gesture symbolized the concern of the Soviet Republic for the proletarian masses.

The Red Garden must become, in place of the ignorant church of popes and priests, a new people’s sanctuary, a Pantheon of heroes of international brotherhood.

In time, a colonnade of statues of men like Plato and Babeuf, Blanc and Delescluze, Lenin and Liebknecht will grow here.

Thanks to the help of Austrian sculptors, former prisoners and now free Soviet citizens, this work has already begun and the first monument is ready.

He [the Red Jew] hesitated for a long time in choosing a historical figure whose bust would be the first to be honored with being erected here.

He thought, for example, of Lucifer and Cain, for both were oppressed, both were rebels, revolutionaries of the highest caliber. But the former is a theological figure, whose supernatural character does not correspond to Marxist views and whose light is extinguished by a decadent society, in whose eyes Lucifer symbolizes fear and hatred.

The second, Cain, is a mythologized character, whose very existence is highly questionable.

That is why his gaze turns to a historical figure who is indisputable for all living on earth, who is also a victim of the religious views of a predatory society…

The one who for two thousand years was innocently crucified on the cross of shame of capitalist interpretations of history. The great Prometheus of the proletariat, the forerunner of the red world revolution, the redeemer of the sins of the twelve apostles of Christ – Judas Iscariot!

The speaker gradually worked himself into ecstasy. The audience hardly understood what he was saying, but, feeling uncomfortable under his burning gaze, they responded with shouts, while most of the Russians piously crossed themselves.

The Jew fell silent, not paying attention to the effect his words were producing. His features twitched painfully and he began again, stammering, to speak about the hour of retribution, about the oppressed apostle, about the dictatorship of the proletariat, about brotherhood, about the International…

But he was talking into nowhere. His face twitched in convulsions, as if lashed by the whip of heart-rending thoughts. He grabbed the podium with both hands, his nails and fingers dug into the red fabric.

The next minute his face suddenly smoothed out, he leaned forward and said mysteriously: “I bring you a message,” and, folding his arms on his chest, he continued: “On me are the sins of all times. In me is the truth. Do you know me? I am the savior of our time,” and finished in a whisper, “I am he.” There was no doubt that he was crazy. He considered himself Judas.

At that moment, disturbing the hot air, the roar of an airplane flying over the garden was heard. After listening to this sound for a moment, the Jew washed his face with his hand and shouted with sudden enthusiasm: “Long live the world revolution!”, after which he left the tribune and, demonstrating remarkable self-control, bowed and asked Dolly Mikhailovna to pull the curtain off the statue.

Blushing, Dolly Mikhailovna took the cord from his hands and pulled it a couple of times, revealing a reddish-red figure with traces of freshly laid plaster: completely naked, superhuman in size, with a face very reminiscent of the features of the commissar, turned to heaven, while her hands passionately tore at the natural hemp rope wrapped around her neck.

As soon as the apostle revealed himself to the audience, the orchestra struck up the “Internationale” and we, inspired by the music, stood with our heads uncovered.

At the other end of the garden, three rifle volleys rang out, quickly following one another. They were not blanks. The ominous whistle of the bullets flying over our heads made me shudder.

God knows where their path ended. The Red Jew said something to Dolly Mikhailovna, after which he embraced her and kissed her right on the lips.

Before I understood what was happening, she turned to me and I felt her soft, elastic-like body clinging to me, the teasing scent of her powder in my nostrils and, at the same time, the warm, sea-like moisture of her blood-red lips.

For a moment it seemed that the daytime heat had burst into flames. Not seeing in my eyes the understanding of what was happening, Dolly Mikhailovna chuckled and turned to another person standing next to her to bestow on him a kiss, which began to pass from mouth to mouth…”

I think comments are unnecessary here. In general, the European provides a lot of unreliable information in his story. The description of his movements raises questions, when he clearly gets confused: where from and where he is going; there is also a discrepancy in the dates. Therefore, some people even doubt the presence of Kehler in Sviyazhsk.

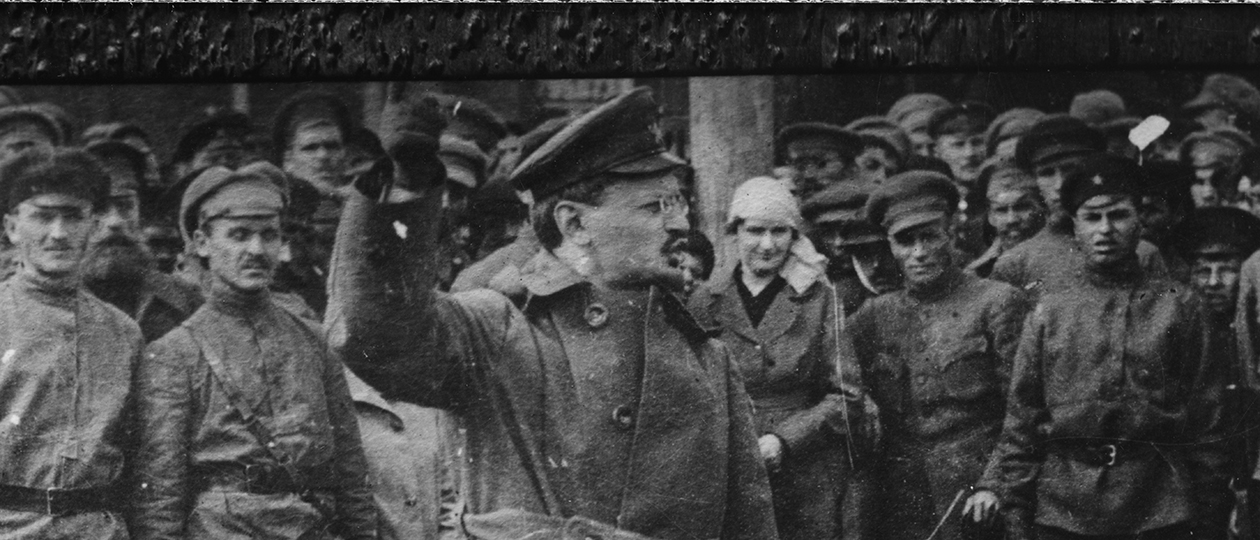

But the most interesting thing is that he calls the settlement Sviagorod, and does not remember Trotsky by name at all, which he says directly (he writes about him as a red Jew and the city commandant), although Trotsky’s figure was no less popular than Lenin’s at that time. And it is rather strange that the guest from Europe did not know what kind of person was in Sviyazhsk.

But there is another witness – a certain A. Varaksin, who in 1923 in Berlin published a book “Along the Roads of Russian Troubles”.

In it, he describes everything that Kehler does (“from the words of eyewitnesses”), only he does not confuse the names and titles. He specifies that Judas was brought from Moscow on an armored train, on which Trotsky also arrived.

He explains the choice of the monument by the fact that, in the opinion of the authors of this initiative, the former apostle is the first revolutionary.

But the authenticity of Varaksin and his book is also rather doubtful. Firstly, this work was mentioned for the first time in 2000 in the Kazan magazine (KAZAN Magazine, No. 2-3, 2000, p. 130, “How It Was”), but no additional information could be found in Russian, English or German.

In addition, from the quotes given in the article, it is clear that the author of 1923 provides rather controversial information regarding those places.

The most striking thing is that he calls Sviyazhsk an island. But it became such only in the 1950s. Therefore, this source is also highly questionable. Some publications on the subject of the monument to Judas refer to stories of old-timers, to local legends.

But such information is difficult to confirm or refute.

There is also information about this event in Sviyazhsk in the “Memoirs” of Prince N. D. Zhevakhov (vol. 2, part 3, ch. 41) – but with a reference to “Tserkovnye Vedomosti”, 1/14 – 15/28 December 1923, No. 23-24, which we have already studied.

If we nevertheless assume that the Danish traveler visited this settlement and saw Trotsky, then, as a number of researchers note, he could simply have made a mistake in the names, which, in principle, he often did in his book.

Kehler knew Russian poorly and could easily have confused Judas with Yudin. The latter led the Latvian riflemen and was killed in the battles near Kazan on August 12.

Yan Andreevich Yudin was buried with honors in Sviyazhsk, and a monument was erected at the site of the grave. It was most likely the Dane, with a great imagination and bad Russian, who considered it a monument to Judas.

Varaksin’s “Memoirs” are a late forgery.