On January 7, 1988, the 9th Parachute Company of the 345th Guards Separate Parachute Regiment began fighting against Afghan rebels, sometimes referred to as mujahideen, at Hill 3234.

In late 1987, the DRA government garrison and local residents in the border town of Khost in Khost Province, besieged by Afghan rebels, found themselves in a difficult situation. The enemy was effectively planning a complete takeover of the district.

This situation developed after the withdrawal of Soviet troops from the Khost district in the spring of 1986, when a major military operation destroyed the Jawara rebel base. Following the Soviet withdrawal, DRA government forces were unable to withstand the enemy onslaught and were blocked in the town of Khost itself, losing control of the road linking it to Gardez. The 40th Army command decided to support the city, which was blockaded by land, with air deliveries of food and ammunition.

The USSR Armed Forces launched a major military operation, “Magistral,” whose main objective was to relieve the city of Khost and deliver food, fuel, and ammunition to the besieged garrison via road convoys.

The 1st and 3rd Parachute Battalions of the 345th Separate Guards Parachute Regiment (hereinafter referred to as the 345th APRR) were involved in the operation. To ensure the convoy’s safety from enemy fire, temporary guard posts were posted on all commanding heights adjacent to the road, along the distant approaches to the road connecting the cities of Gardez and Khost. The 3rd Airborne Battalion (hereinafter referred to as the 3rd Airborne Battalion) was tasked with defending the road from the south, where an enemy fortified area known as Srana was located.

The 3rd Airborne Battalion operated in close proximity to the Afghan-Pakistani border. Only two of the battalion’s three organic companies (the 8th and 9th Airborne Companies), totaling 85-90 men, were allocated to combat operations on foot in the highlands. The battalion’s combat mission was to capture several heights adjacent to the Gardez-Khost road, from which the enemy was directing artillery fire on the Soviet troop group. The 8th Company was tasked with capturing three heights. The 9th Company was tasked with capturing two unnamed heights, marked on maps as 3234 and 3228, from which the road was visible for 20-30 kilometers.

On December 27, the reconnaissance platoon of the 3rd Airborne Battalion, supported by fire from the 9th Airborne Company (hereinafter referred to as the 9th Airborne Company), captured Hill 3228. The subsequent assault on Hill 3234 was unsuccessful. By the night of December 27-28, after an artillery barrage, Hill 3234 was taken in a second assault. As a result, the Gardez-Khost road was completely under the control of Soviet and Afghan government forces. Vostrotin, commander of the 345th Airborne Regiment, approved the decision of Major Ivonik, commander of the 3rd Airborne Battalion, to concentrate all three platoons of the 9th Company on Hill 3234, located 7-8 kilometers southwest of the middle section of the road, as it was tactically more significant.

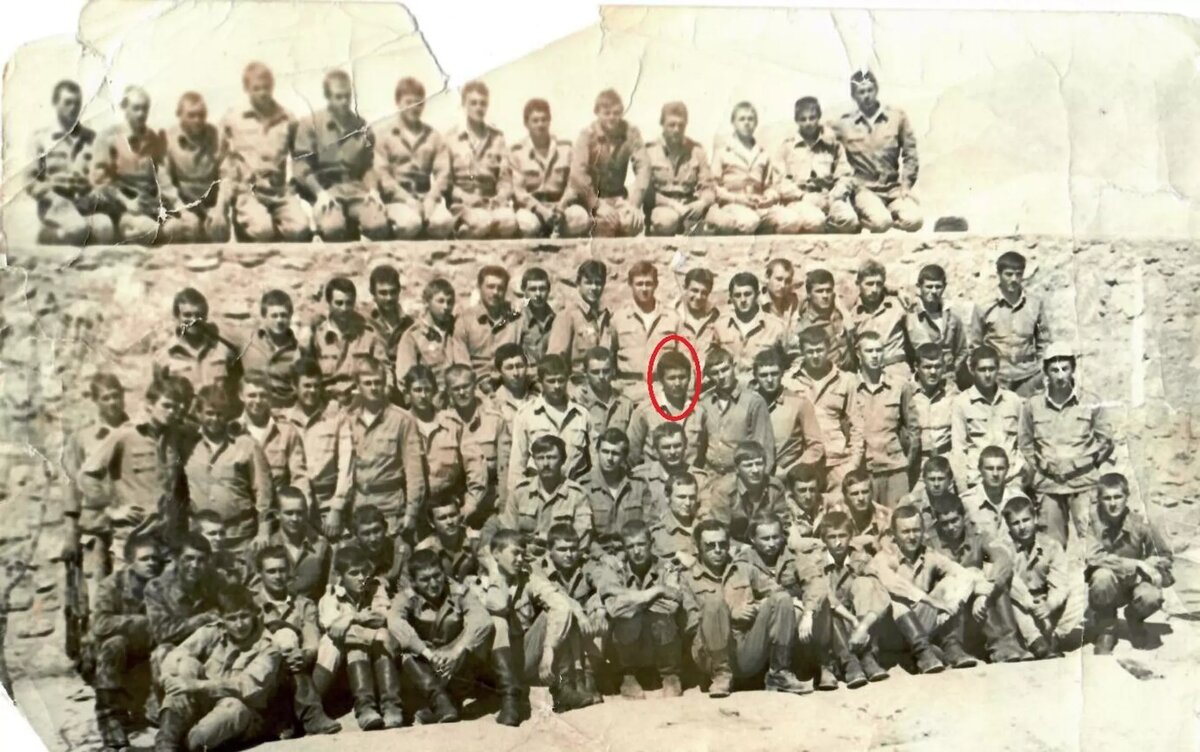

The 9th Company was under the command of Senior Lieutenant Sergei Tkachev, who served as deputy company commander. Necessary engineering work was carried out at the heights, constructing structures to protect personnel and firing positions, and laying a minefield on the southern side. The company was reinforced by a heavy machine gun crew.

In fact, only 40% of the company’s personnel—39 men—were actually deployed to defend this height. Senior Lieutenant Ivan Babenko, commander of the command platoon of the 2nd Howitzer Artillery Battery of the 345th Separate Airborne Regiment’s artillery battalion, was also assigned to the company as an artillery spotter.

On December 30, 1987, the first supply convoys began moving forward.

On January 7, 1988, at 4:30 PM, the first report of shelling of the company’s position with recoilless rifles and grenade launchers was received. Due to the remoteness of the position, air and artillery support was provided. Taking advantage of the mountainous terrain, bandits sneaked up on the position. The first attack fell on the remote machine-gun nest of Guard Junior Sergeant Alexandrov.

Machine-gun nests were destroyed with grenade launchers, supported by machine-gun fire. Under heavy fire GuardJunior Sergeant Alexandrov acted decisively and managed to secure the withdrawal of his comrades to another position. He fired back until the machine gun jammed. When the enemy approached, he successfully threw five grenades. Vyacheslav Alexandrov was killed by a grenade explosion.

Things escalated from there: with a ten-to-one numerical superiority, there were a total of twelve attacks from three directions, including through a minefield. The second machine gunner, Andrei Melnikov, was killed. The third machine gunner, Andrei Tsvetkov, constantly shifted positions, running from one line to another and holding his ground to the end. The enemy approached to within fifty meters, in some areas as close as ten. The battle lasted until four in the morning. Throughout this time, powerful artillery support was provided, with the fire directed by a spotter in position. At a critical moment, when ammunition was running low, a reconnaissance platoon arrived to the rescue, immediately engaging in combat and decisively deciding the outcome in favor of the Soviet paratroopers.

As a result of the twelve-hour battle, the company achieved an unconditional victory. The heights were not captured. Having suffered heavy losses, the numbers of which are unknown, the dushmans retreated. Six soldiers of the 9th Company were killed and 28 were wounded, nine of them seriously. Junior Sergeant Vyacheslav Alexandrov and Private Andrei Melnikov were posthumously awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union.

Don’t fall for the story that “in the chaos of withdrawing a huge army, the company was simply forgotten on an unused hill,” perpetuated by the notorious film by Bondarchuk Jr. The actual losses of Soviet soldiers in the battle of the 9th Company amounted to six men. The paratroopers were covered by a howitzer battery, and a special forces detachment was sent to their aid. It’s just that Fyodor Sergeyevich, who inherited nothing from his father except his last name, not only reshot “Full Metal Jacket” and “Platoon” frame-by-frame, but also, for added drama, stitched together the battle of the 9th Company and the March 2000 battle of the 6th Company of the Parachute Regiment of the 76th Guards Airborne Division at Hill 776. That’s how it happened that the Swedes from the VIA “Sabaton” sang about Hill 3234 more respectfully than Bondarchuk filmed it.

And, mind you, no one scolds Bondarchuk Jr. anymore, labels him a foreign agent, or revokes his contracts.

P.S. Just for the record. Afghan terrorists are regularly referred to as mujahideen. That is, fighters for the faith. This is fundamentally wrong. The USSR made no attempt whatsoever to undermine the religious foundations of the Afghan people. This means they weren’t fighting for faith, but for someone’s money—in other words, they were simply dushmans. A dushman is an enemy, a bearer of evil intentions.