In mid-80s, I bought a photo album with this title in a Washington-based book store.

As a result, by pure chance, I learned about Russia’s pioneer of color photography who at the beginning of the 20th century carried out a titanic task of taking hundreds of superb pictures of what used to be called Russian Empire.

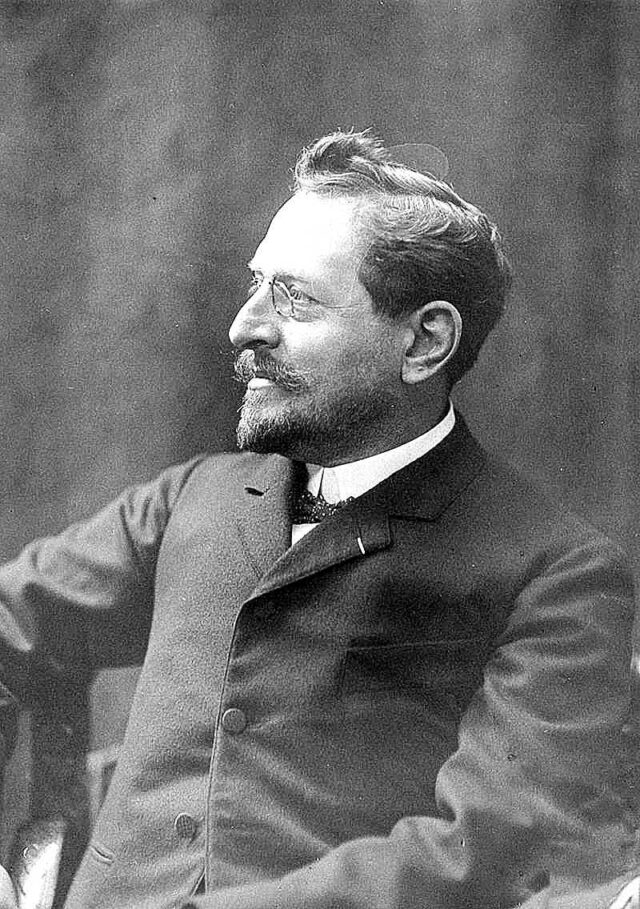

Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii was born in 1863 in St. Petersburg. 26 years later he went abroad to teach chemistry.

He lived and worked in Charlottenburg, then in Paris where he got interested in color photography, and succeeded so much that he was awarded the Grand Prix at the Paris World Exhibition.

Upon his return to Russia he devoted himself to photography forever. He opened a photo studio in St. Petersburg, founded Russia’s first photography training courses, and published a series of popular science works on this subject.

During Russo-Japanese War, Sergei Mikhailovich went to Korea (his pictures were published in Russia’s Ministry of War yearbook). Returning home, he continued his experiments with color photography and gave a report at a meeting of the photo section of the Russian Imperial Technical Society.

After that, Prokudin-Gorskii was elected an honorary member of the Russian Photographic Society patronized by Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich who was Prokudin-Gorskii’s great fan.

Nicholas II, Russia’s last emperor, liked taking pictures, too, and in winter of 1909 Sergei Mikhailovich was invited to Tsarskoye Selo, a residence of the Russian imperial family, for demonstration of his color photos.

Visibly impressed, during tea break Nicholas II took Prokudin-Gorskii aside:

— How do you see the future of your invention? Can it be of any benefit to our Fatherland?

— Projection devices, installed at educational institutions, will become an indispensable aid to teacher — Sergei Mikhailovich said in response.— Today, photography is the only way to capture the image of our Fatherland without distortion. Besides, soon we will celebrate the 200th anniversary of defeating Napoleon’s invasion, and I would like to immortalize the battlefields, churches and monuments to the glory of the Russian army.

Asking for Tsar’s support, Prokudin-Gorskii was not driven by greed, careerism or vanity. Being an outstanding scientist and a pioneer photographer, he was an educator in the best traditions of the Russian intelligentsia.

Sergei Mikhailovich dreamed of the time when even the most remote school would be equipped to show slides as teaching aids.

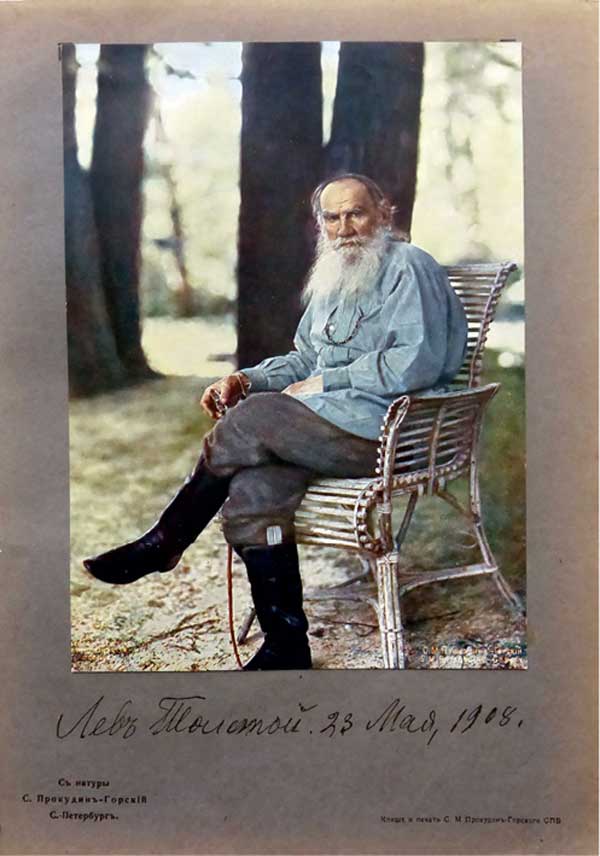

In May 1908 Sergei Mikhailovich managed to take a unique color photo portrait of Leo Tolstoy. The genius of world literature was known for his extreme hostility to anything that, in his view, contradicted personal modesty but he made an exception for Prokudin-Gorskii. As a result, we can now enjoy the “Leo Tolstoy in Yasnaya Polyana” photo.

With Tsar’s blessing, in summer of 1909, the first photoethnographer in Russia’ history got a steamboat and a car-photo lab at his disposal, and, accompanied by his 20-year-old son Dmitry, set off on an unprecedented journey across the world’s largest country that lasted for 5 years.

The existing information about Prokudin-Gorskii is pretty scant, but even scantier is the information about his method of photography and the equipment he used.

To the best of our knowledge, Sergei Mikhailovich improved the method developed initially by Scottish physicist Jamed Clerk Maxwell and English photographer Thomas Sutton, who surmised that a color photograph can be obtained by mixing red, blue and green colors.

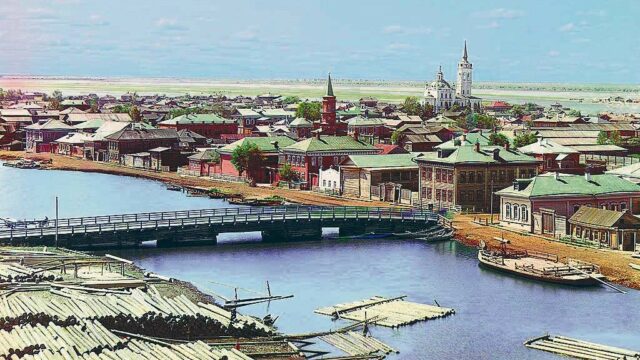

The quality of Prokudin-Gorskii’s color pictures is amazing even by today’s standards. Besides he made an unprecedented detailed photo portrait of pre-revolutionary Russia.

After the October Revolution of 1917, Sergei Mikhailovich emigrated, taking abroad 1,600 photographic plates with Russian images. He settled down in France where he died in 1944 soon after celebrating the 81st anniversary.

In late 40s, the American Council of Learned Societies published a 9-volume History of Russian Arts edited by Igor Grabar and translated by Princess Maria Putyatina. She recalled that at the beginning of the 20th century her father-in-law was acquainted with Prokudin-Gorskii.

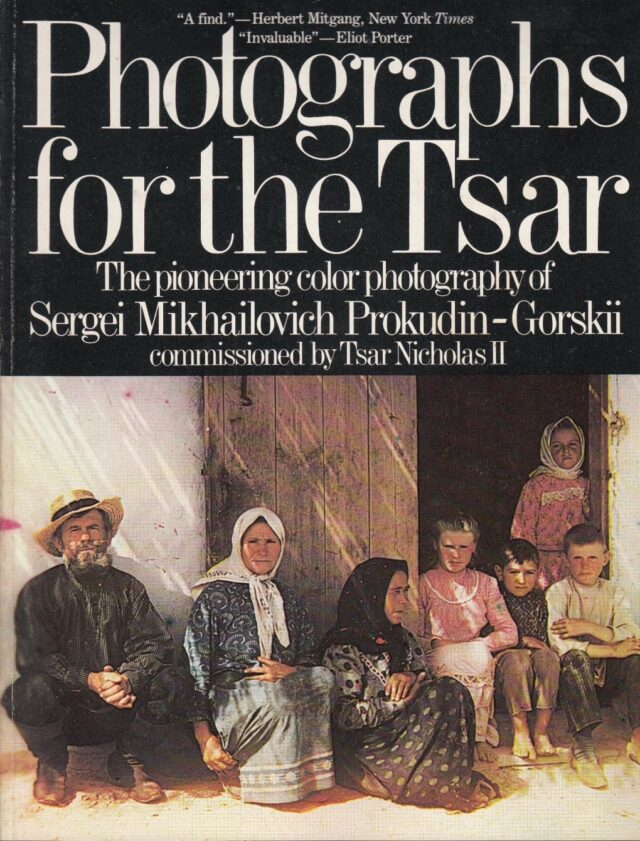

Through the Rockefeller Foundation, it was discovered that Sergei Mikhailovich’s daughter and son still lived in Paris and agreed to cede their father’s creative legacy for $5,000. 30 years later Dial Press published Photographs for the Tsar.

In late 1989, I brought this book to Ogonyok, Soviet analogue of Life magazine where I used to publish my articles since mid-70s. Dmitry Nikolayevich Baltermants, editor of Ogonyok’s illustrations department and a famous photographer himself, was astonished:

— Color pictures of such a quality, taken eighty years ago!..

He was especially struck by the portrait of Leo Tolstoy:

— When we published this photo in Ogonyok about eleven years ago we believed it to be a colorized black-and-white picture…

I said that I could write an article about Prokudin-Gorskii for Ogonyok, adding:

— It would be a special honor for me to become the first Soviet journalist to introduce local readers to Russian pioneer of color photography.

— And we will be only happy to run such a piece! — Baltermants echoed. — We’ll start preparations right away. To do that we’ll make copies of the most impressive pictures from your book.

Noticing my hesitation (the album I brought to Ogonyok was unique in our country at that time), Dmitry Nikolaevich said:

— Don’t worry! We will give “Photographs for the Tsar” back to you safe and sound.

After a while, I brought my article to Ogonyok. The editorial staff member Natalya Zagalskaya said that it would be published in the first quarter of 1990. And she returned the worn photo album:

— Sorry, it so happened during copying.

I went on a two-month business trip abroad, and upon my return I looked through the published issues of Ogonyok. One of them contained a 4 pages-long article on Prokudin-Gorskii, full of color illustrations including a portrait of Leo Tolstoy.

The accompanying text, though, differed from my own article, and was bylined by… Natalia Zagalskaya. Thus, without my knowledge and behind my back Ogonyok’s editors who proclaimed themselves to be the most faithful supporters of perestroika and used the words “justice”, “decency”, “ethics” as their slogans, behaved in a most dishonest way with their own award-winning author.

Needless to say that I broke any relationship with them, comforting myself by the thought that on my initiative and with my participation 34 years ago Ogonyok introduced our contemporaries to an outstanding compatriot.