Since the fall of the Roman Empire, the dominant aspects of human life were the church, the state and the army. Accordingly, the activities of merchants were regulated by the state and the church with the help of military forces.

The already difficult economic situation was aggravated by strict restrictions, trade was at rock bottom, city dwellers massively populated the countryside and were forced to “roll back” to barter, so there was no need for early medieval advertising. Only the church was doing well. It was at this time that confessional proto-advertising was in full swing, even Wall Street brokers would envy such PR, this was, of course, due to total Christianization.

The Christian cult emphasized ostentation, framing its relics with gold and jewelry, building luxurious temples and churches for worship, dressing the clergy in silk, brocade, and mitres embroidered with pearls. In addition, they did not skimp on magnificent religious processions, which replaced primitive rituals and ancient holidays.

These religious show programs were incredibly popular among the poor population, which at that time made up almost 99% of the total population. Imagine: everything around is expensive and rich, smells delicious, shines beautifully, they sing every day, and even treat you to something. This made an indelible impression on a beggar who had never seen anything more beautiful than a pile of manure behind his house.

All this splendor was generously flavored with sermons, the purpose of which was to attract as many people as possible to their ranks, thus the suggestive method of influence was born, which is the ESSENCE of the nature of all known advertising.

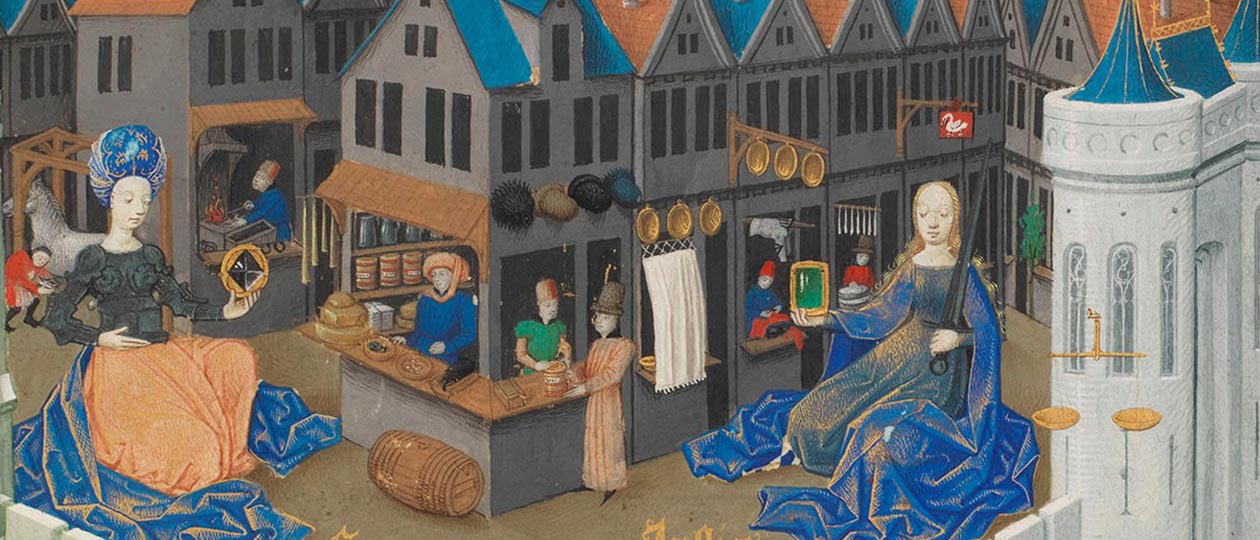

Starting from the 11th century, part of Europe gradually began to come back to its senses, the process of urbanization of cities was revived, and therefore the demand for advertising increased, but for better efficiency new rules and regulatory bodies were required.

Among the first to form their professional charter were enterprising wine heralds from France, they filled glasses with wine and went out into the street, loudly praising the drink, however, it was forbidden to advertise wine on weekends and holidays.

The position of herald was endowed with some administrative rights and was strictly regulated by royal orders. In Germany, the “advertising shop” was completely taken over by the authorities and it was forbidden to shout anything without first coordinating it with the herald.

Outdoor advertising-heraldry was also actively developing; artisans borrowed this idea from the knights. By the 13th century, guild organizations of artisans were gaining great popularity; they had their own uniform corporate style, uniform coat of arms, banner and symbol.

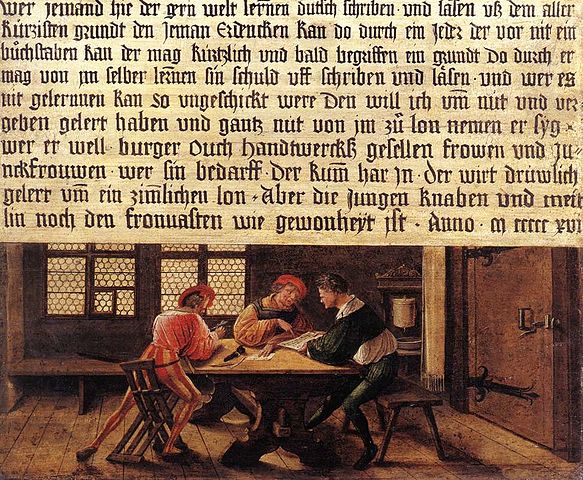

By the beginning of the 15th century, the need to disseminate information had grown significantly and could no longer be satisfied with only corporate signs, street shouts and hand-written posters on the walls. With the advent of the first printing presses, invented in the 1440s by Gutenberg, paper advertising literally flooded everything around; by the beginning of the 16th century, more than 200 printing houses were working at full capacity.

But the percentage of the literate population who could read the ads was insignificant in total, so the posters were always accompanied by colorful pictures, for example, the picture (Hans and Ambrosius Holbein) shows an advertisement for a reading and writing tutor with a guarantee of results.

If the potential student fails to master the literacy test, the teacher promises to return the money. (Probably, no one wanted to admit that they were stupid and studied diligently).

This is where journalism and the media originated, they had just begun to form their laws and rules, by which they still exist.