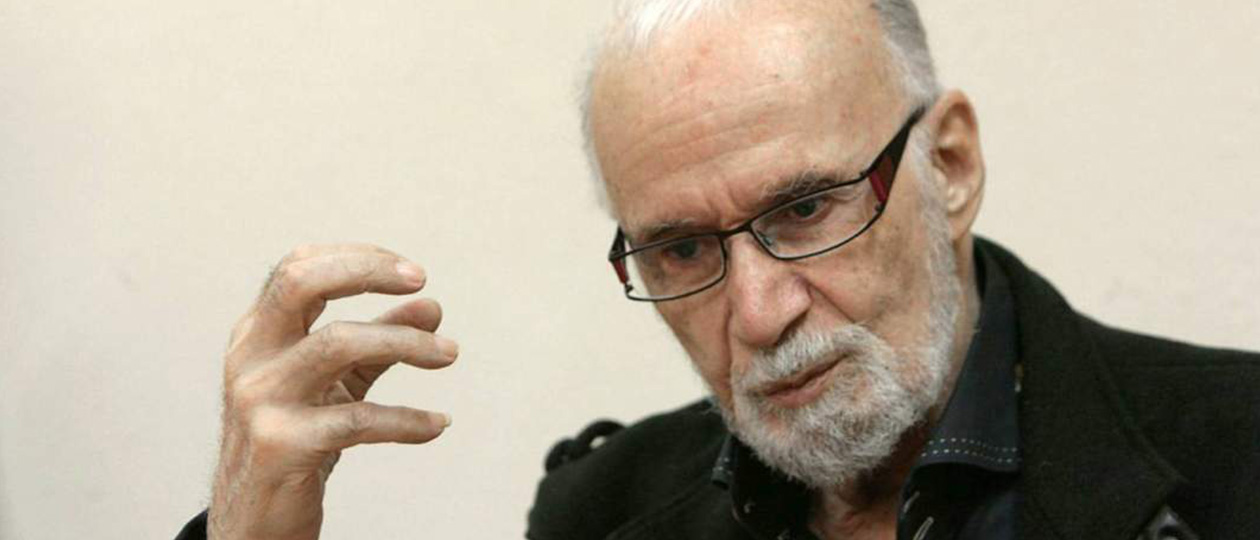

Melor Sturua As a Mirror of Soviet Elite’s Evolution: Part I

Soviet authorities upheld the decision to declare Nagorski persona non grata.

Thus, Melor Georgievich managed to return to the United States only 8 years later, when our country hit Catastroika, as Alexander Zinoviev, Soviet philosopher, writer, and sociologist, branded Perestroika.

In 1990, Sturua started teaching at the University of Minnesota. Next year he showed up at the Voice of America radio station to repent of his many years of service to the system, which, as Melor Georgievich finally realized after spending nearly 50 years in Kremlin’s inner circle, deserved nothing but hatred, contempt, and condemnation.

By doing so, the holder of two Orders of the Red Banner of Labor, the Order of Friendship of Peoples and the Badge of Honor, who only recently would “turn inside out the cannibalistic morality of the Yankee imperialism,” earned lots of kudos at American websites. Not a single Soviet journalist had ever been honored that way in the United States.

Some 3 years before his public repentance on the Voice of America, Melor Georgievich recounted his childhood and youth in a series of publications in “Nedelya”, Sunday supplement to “Izvestia”. In them, he told how he and his father used to pay regular visits to Stalin.

As a child, Melor sat on bloody tyrant’s lap and nearly pulled his moustache. As a student, he played volleyball and hit the ball so hard that he broke the pince-nez of Lavrenty Pavlovich Beria from the opposite team.

If we are to believe Sturua (in such cases Izvestia’s sports editor Boris Fedosov would say: “Divide what you hear by sixty-nine”), the all-powerful chief of the Soviet punitive organs glanced ferociously at the darling of fate, but preserved him for posterity.

This was culminated by “The Grey Cardinal” article. In it, Melor Georgievich, in his typical bright style, mocked Suslov who had been buried by the Kremlin wall 6 years before. Depicting Mikhail Andreyevich as a man in a suitcase, his former relative recalled that Suslov would wear galoshes even in summer, and claimed that he trampled and stifled any shoots of free thought in the USSR.

30 years later, on occasion of his 90th birthday, Sturua gave a lengthy interview to Moscow-based MK’s columnist Alexander Melman. He recalled his youth when he used to provide girls to a friend who later emigrated to England.

He emphasized his distinction from other famous Soviet journalists, i.e. Izvestia’s Kondrashov and Bovin, Pravda’s Zhukov and Ovchinnikov, and Central Television’s Kaverznev: “Differently from me, they all held the title of political observers. This means that I did not have special rations, access to the Central Committee, or any other privilege.”

Still, “Once Bovin and I were spending good time at the House of Journalists. A group of young journalists spotted Bovin and surrounded him, while I was sitting quietly. Then Bovin said: “This is Sturua,” and they all rushed towards me.”

Melor Georgievich also claimed that he, “was very close to Khrushchev. I accompanied him on all of his trips to the Oriental countries. He used to call me Black: “Black, come here!” And I had very interesting meetings with Gorbachev. He treated me well. He would say: “Melor is quite right about this or that.”

“And how was it with Yeltsin?” – Melman inquired.

«Dmitry Simes and I dragged him to America” – Melor said in response. – “We arranged his show in the States. “An elephant was led through the streets”…»

Speaking about his work as a Washington correspondent for Izvestia, Sturua revealed that the US authorities suspected him of an attempt to commit a terrorist act against President Reagan: “I was driving with my wife, and they stopped me.

I told my wife to run quickly to our embassy. And they brought me to a bunker. I said: “What’s going on?” They explained. I pounced back on them: “Look at what you’ve brought this country to. This is outrageous!” I raked them over the coals. They apologized, and let me go.”

Also, Sturua recalled how the American authorities tried to exchange him for Nagorski: “He was absolutely clean. He didn’t work for any intelligence service. And what did the Americans do? They threw me out because I was clean, too. [Did he want to say that the rest of three dozen Soviet correspondents in the US were not clean? – A.P.] The Americans tried to protect Nagorski. But no one protected me here. Instead they attacked me, they harassed me. All this persecution was led by the director of TASS, son of a bitch!“

MK ran Sturua’s interview with this headline: «Melor Sturua: “I wavered with the party line, but I was not a scoundrel.»