In August of 1983 16-year old Andrei Berezhkov, youngest son of Valentin Berezhkov, first secretary of the USSR Embassy, sparked a diplomatic confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union.

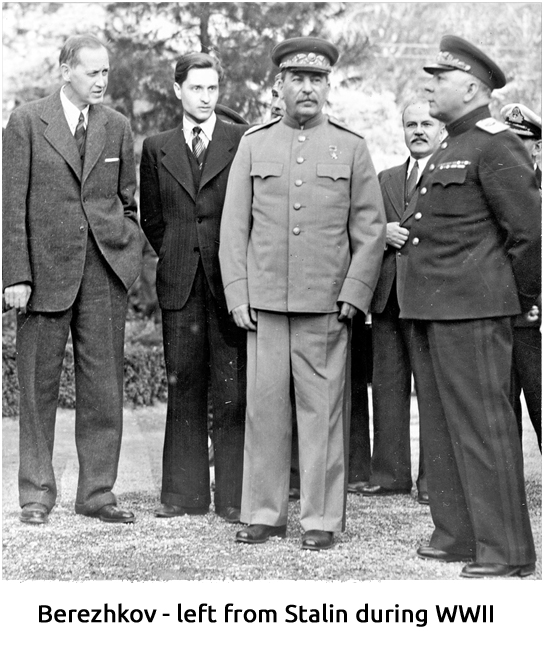

Former Stalin’s interpreter who had translated Soviet leaders’ talks with Hitler, Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt, in the United States V. Berezhkov represented the Institute for US and Canadian Studies, a Soviet think tank providing valuable information and recommendations to the Kremlin.

Together with his second wife Lera, who was 22 years younger than him, and their son Andrei he rented an apartment in a neighborhood near Washington where a few more high ranking Soviet diplomats as well as several Soviet journalists also resided.

V. Berezhkov spoke fluent English and spent lots of time travelling across USA as a guest speaker at local universities and other organizations anxious to learn the Soviet point of view of bilateral relations.

Lera usually accompanied him while Andrei would be often left behind either completely alone (if his parents travelled just for a couple of days) or with Soviet friends who lived nearby. Many Soviet employees, stationed in USA, did the same but it was a special case with the Berezhkovs who made it a standard practice.

As a result Andrei was on his own plenty of time and one day when his parents departed by plane on yet another business trip he took his father’s car and drove to New York. Two days later The New York Times published Andrei’s letter to President Reagan pleading to provide him with political asylum.

«My son was always a little rebellious, he always wanted his independence. If he had been born at another time such independence would have brought him to Siberia or worse», claimed Valentin Berezhkov some 10 years later upon emigration to USA where he started teaching and lecturing at Pomona College in Claremont, California, the same state his parents settled down in late 40s after they had fled Kiev in 1943 just before the Red Army liberated Ukraine’s capital from German invaders.

Staying in California, Valentin Berezhkov granted sensational interviews like «I could have killed Stalin» and published his memoirs, «At Stalin’s Side», 4 years before his death in 1998. Upon fact checking this book Alexander Philipov, a Russian historian, came to a conclusion that it was full of unproven data, hearsay and pure phantasy.

Anyway, in 1983 Cold WarII, as I called the resumed tension of Soviet-American relations after a brief period of détente, was in full swing. Only a few months earlier Ronald Reagan called the USSR an Evil Empire, and American officials did not hesitate to use a Soviet adolescent in yet another twist of what we call now information wars.

The same happened 7 years before at Summer Olympic Games in Montreal when another Soviet adolescent, Sergey Nemtsanov, after his failure in diving competition, was nearly lured to defect to the West. While it took place in Canada, that country’s Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau made it clear to the Soviet Ambassador that the seducers had American ID cards.

So, back to August, 1983. The USSR Embassy demanded that Valentin Berezhkov should get a chance to see his errand boy. The US State Department complied with this request, and after meeting his father Andrei renounced his plea to President Reagan and agreed to rejoin his parents.

A few days later the whole Berezhkov family prepared to board an Aeroflot plane en route to Moscow. As soon as local media found it out a swarm of journalists rushed to the Dulles airport in Washington suburbs.

They were not disappointed. Passing by them and being a great fan of Rolling Stones, Andrei waved his hand and said in perfect English, «Please pass my best regards on to Mick Jagger!».

When everybody else boarded Il-62 and it was about to take off, the Soviet pilot got a request from airport authorities to switch off the engines and to take one more person on board who turned out to be Richard Burt, the third ranking official at US State Department.

Accompanied by two cops, Burt approached the row where the Berezhkov family was seated and said: «You and the rest of the passengers are not going anywhere unless Andrei confirms loud and clear his willingness to return to the USSR on his own good will».

Andrei Berezhkov had done just that the day before during his meeting with US officials in Washington but Richard Burt was not satisfied. An overambitious person, he loved public shows and lost no opportunity to display his authority.

Most importantly, though, he was driven by anti-Sovietism of such magnitude that he had little competition in US capital. Twelve days later, on September 1, 1983, a South Korean passenger plane intruded the USSR air space in Far East and was shot down by a Soviet fighter.

The Reagan administration took full advantage of this tragic incident, plus Kremlin’s incompetence in info wars, and formed a task force, composed of White House, State Department, CIA and Pentagon officials entitled to use this opportunity to reinforce the Evil Empire image of the Soviet Union. Richard Burt was put in charge of this team which made him feel overjoyous: «We got those bastards! We finally got them!».

And Andrei Berezhkov who, as The Washington Post put it, «grew up amid the privileges of the Soviet elite and because of his family’s connections got away with the botched defection that turned into an international incident», upon his return to Moscow entered a special school for children of the said elite.

While his classmates drew pictures of red stars atop the Kremlin, Andrei sketched Soviet tanks in Afghanistan. For doing so he got a reprimand, but nothing more. And as soon as Gorbachov launched perestroika, the youngest son of Stalin’s former interpreter, to quote The Washington Post once again, «moved enthusiastically from the privileges of communism to the privileges of capitalism».

«He was very glad when perestroika came and even sported a ‘Gorby’ pin his father had sent him from America», recalled a college friend of his.

In 1990 Andrei quit the prestigious Institute of Space Research, where he had been working as an entry-level engineer, to enter the gray area of minor capitalist enterprise.

Three years later and exactly 10 years after the international turmoil he caused in Washington Andrei was shot to death in his Moscow office by a business companion who took his own life the same way.